By Dr. Jim Dahle, WCI Founder

By Dr. Jim Dahle, WCI FounderEarly retirement provides some amazing opportunities tax-wise. It's entirely possible to pay no taxes at all during early retirement. However, that isn't usually the goal. Still, most early retirees are paying less in taxes (at least as a percentage) than at any other point since they started earning and, in many cases, less than they will be paying in later retirement after Social Security and Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) kick in for them.

In today's post, we'll go over a few examples of early retirees that illustrate important principles of taxation during this time period.

You Only Pay LTCG Taxes on the Gains

The Johnsons made big money for a decade (about $1 million a year) and paid correspondingly high tax rates. About 1/3 of their income was going to payroll, federal income, and state income taxes. They were sick of it. So, they saved up a whole bunch of their income, invested it wisely, and retired at 50. They have some tax-deferred and tax-free accounts, but like most early retirees, they have a substantial taxable account too. That is what they are planning to live off of during their early retirement years.

Their total nest egg is about $4 million, and they've decided they can safely spend about $150,000 a year. Their taxable account is about $1.5 million. A significant chunk of that money just went into the account in the last few years, and so the gains are minimal on those tax lots. Naturally, they've chosen to sell the lots with the highest basis first. The taxable account kicked off $30,000 in qualified dividends. They sold $120,000 worth of high-basis shares they had owned for at least a year—only about $15,000 of that $120,000 consisted of gains. This amount could be even less if they've been carrying forward capital losses from tax-loss harvesting. They also earned a little interest on the cash in their savings account, about $5,000. The total of their taxable income was:

- $5,000 in ordinary interest

- $15,000 in long-term capital gains

- $30,000 in qualified dividends

- Total: $50,000

What is their tax bill? The standard deduction is $29,200 [2024]. Their taxable income is only $20,800. The ordinary interest would be taxed at $0 because it is more than covered by the standard deduction. The rest of their income is in the 0% qualified dividends and 0% LTCGs brackets. So, they pay nothing in tax. Nothing in federal income tax. Nothing in payroll taxes. While state-dependent, they quite possibly also pay nothing in state income taxes (they actually would owe about $1,000 in state tax if they lived in Utah).

The Johnsons have gone from paying over $300,000 a year in taxes to paying $0 a year in taxes. Pretty sweet, right? Actually, most people would argue that this setup isn't very wise for them and that they'd be better off selling lower-basis shares, doing Roth conversions, or even tax-gain harvesting to at least maximize the benefit of that 0% bracket and maybe even the 10% and 12% brackets.

More information here:

Life in the 0% Long-Term Capital Gains Bracket

How to Use Tax Diversification to Reduce Taxes Now AND in Retirement

IRMAA and PPACA Subsidies

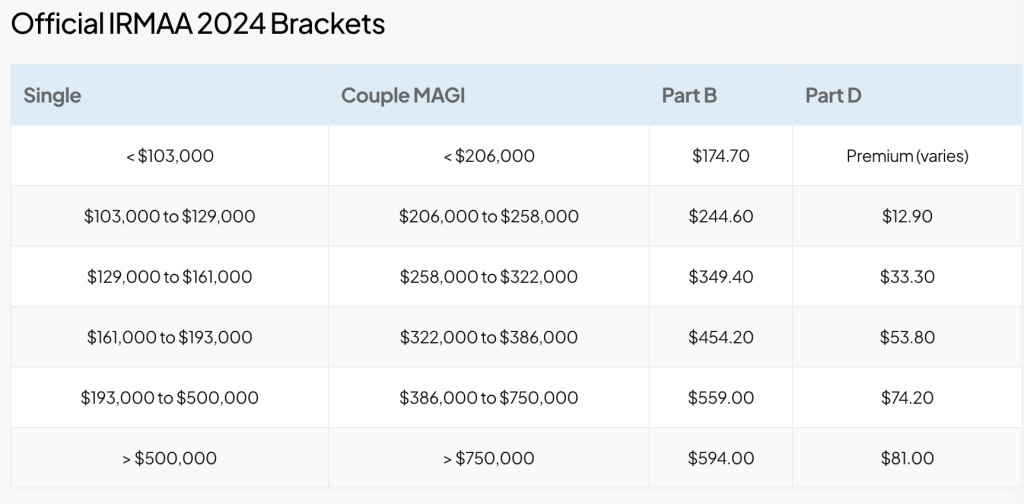

There are two other factors that come into play that aren't usually considered when you think about taxes. The first is called IRMAA, the Income Related Monthly Adjustment Amount for Medicare. Basically, if you have more taxable income in retirement, Medicare costs you more than it otherwise would. Here are the IRMAA brackets:

These numbers are Modified Adjusted Gross Incomes (MAGI) (not a taxable income), but still, the Johnsons are way below where they would have to start paying IRMAA. This wouldn't apply anyway, since they're 50, not 65, and don't qualify for Medicare yet.

The second factor, which is relevant to the Johnsons' situation, is the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) subsidies. Buying health insurance off the PPACA exchanges is usually a good move for early retirees. While health insurance isn't cheap for people in their 50s, the subsidies for someone with income so low that they don't even pay any taxes are substantial. For the Johnsons with a $50,000 MAGI, their health insurance subsidy will be $1,147 per month or $13,764 per year. That may or may not cover the entire premium, but it's basically the equivalent of almost $14,000 a year in tax-free income and nothing to sniff at.

Even with a MAGI of $150,000, they'd still be getting a subsidy of $257 per month. The subsidies are normally paid to those with income ranging from 100% of the Federal Poverty Level (138% in states that have expanded Medicaid) to 400% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL). FPL is determined by geographic area and family size. For a family of two in most states, it is $19,750 for 2024. So, 400% of FPL is $79,000. However, through 2025, that 400% income cap doesn't even apply, thanks to the American Rescue Plan and Inflation Reduction Act. Here's a good resource and a calculator if you'd like to learn more about PPACA subsidies.

More information here:

Healthcare in Retirement Could Cost You $500,000; Here’s How to Plan for It

What If You Have No Taxable Account?

The Gonzalez family in Texas is actually wealthier than the Johnsons. I guess we shouldn't be surprised since they didn't retire until age 55. They have $6 million. However, they've taken advantage of access to a wide variety of retirement accounts throughout their careers and even done a few Roth conversions. Their $6 million is $4.5 million in tax-deferred accounts ($2 million in IRAs, $2.5 million in 401(k)s, and $1.5 million in Roth IRAs, of which $400,000 is contributions). They're planning to spend $200,000 this year and are trying to decide how they should take it.

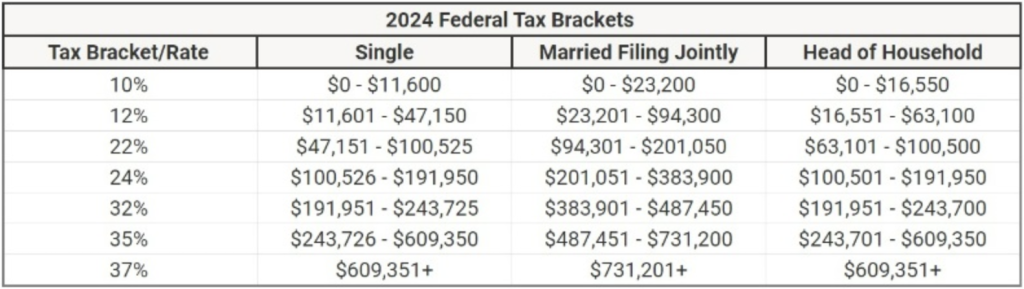

They know that the Age 59 1/2 rule only applies to traditional IRAs and Roth IRA earnings. They figure it will be easy to avoid that 10% penalty. They'll just take tax-deferred money from the 401(k)s where the penalty doesn't apply and use contributions/conversions to the Roth IRAs. Looking at the brackets, they see this:

They figure that paying taxes at 12% is a good deal but that 22% isn't such a good deal. That allows them to take $94,300 + the standard deduction of $29,200 for a total of $123,500 out of their 401(k)s. They'll take the other $76,500 out of their Roth IRAs. Their total tax bill is $10,852. It's not $0, but it's dramatically less than they were paying before retirement and only about 5% of what they can spend.

What About Kids?

While many people don't retire until their kids are gone or even out of college, what if that's not the case? There are “kiddie benefits” in the tax code that most high-income professionals are normally phased out of and can't get. That might not be the case for an early retiree. What if the Gonzalez family still had a 16-year-old at home in 2024? That's a $2,000 child tax credit. Now, their tax bill is only $8,852.

That child has an older sibling in college. They easily qualify for the American Opportunity Tax Credit (AOTC), available up to a MAGI of $180,000 for a married couple. Since they paid $15,000 in tuition, they qualify for the entire $2,500 AOTC, reducing their tax bill to $6,352.

Maximizing the Situation

Careful planning in these early retirement years can go a long way. You can have plenty of spending money without much of a tax bill, but you can also work the system to lower future tax bills using “tricks” that cause you to pay a little more in taxes now but reduce future tax bills for you or your heirs. These include tax-gain harvesting and Roth conversions. Let's go back to the Johnsons who have decided they want to do as big of a Roth conversion as they can while not paying taxes at more than 12%. How much of their tax-deferred accounts can they convert this year?

Their taxable income was only $20,800. But most of that was qualified dividends/LTCGs, and those stack on top of any Roth conversion, which is taxed as ordinary income. Still, they don't want to be bumped into the next QD/LTCG bracket (15%). That bracket starts at a taxable income of $94,050. That is just slightly lower than the top of their 12% tax bracket ($94,300). At any rate, the difference between $94,050 and $20,800 is $73,250 and that is the amount on which they're going to do a Roth conversion. That will cost them $8,326 in additional tax. That's still a pretty good bargain, although it would reduce any PPACA subsidy.

What if instead they decided to tax-gain harvest? The equivalent would simply be to sell low-basis shares rather than the high-basis shares they were planning on selling. Since the top of the 0% LTCG bracket is $94,050 and they've only got $5,000 in interest and $30,000 in qualified dividends, they could realize gains of as much as $94,050 + $29,200 – $5,000 – $30,000 = $29,850 before having to pay any tax. By carefully choosing tax lots to sell, they can probably get pretty close to that for their $115,000 in spendable income and still pay nothing in tax (other than a reduced PPACA subsidy if applicable). If they were willing to pay 15% in tax (and I'm not saying they should), they could sell any shares they wanted and tax-gain harvest most of the others as the 15% LTCG bracket extends to $583,750. However, the PPACA/NIIT taxes (3.8%) would kick in at $250,000 of taxable income.

More information here:

Why So Many Non-Qualified Dividends? Let’s Look Through My Tax Info to Figure It Out

Principles to Remember

What good is a WCI post without a list? Here's what to think about when considering taxes in early retirement.

- Taxes can be very low in retirement, especially early retirement before Social Security, pensions, and RMDs. You can just enjoy the low taxes, or you can take advantage of the opportunity of being in those low brackets to do Roth conversions and possibly even tax-gain harvest.

- Due to healthcare costs, there is more to the calculations than just taxes. Consider the impact on PPACA premiums and, later, IRMAA surcharges.

- The 10% penalty applies to IRAs before age 59 1/2, but so long as you've separated from the employer, 401(k)s and 403(b)s are free game starting at 55. There is no 10% penalty when it comes to 457(b)s. This is a good reason for retirees to wait to roll money out of a 401(k) until they are 59 1/2. However, there are lots of exceptions to the 10% penalty, including health insurance premiums, educational costs, and early retirement via SEPP withdrawals.

- While you generally want to sell/spend high-base shares first, there are times when it can make sense to sell lower-base shares or even tax-gain harvest to take advantage of the 0% (or possibly even the 15%) LTCG bracket.

- Qualified dividends and long-term capital gains stack on top.

- Roth IRA contributions can come out penalty-free at any time. Conversions (i.e., Backdoor Roth IRA contributions) require a five-year waiting period from the time of the conversion before the principal comes out penalty-free.

- Tax diversification is very useful. You can carefully blend tax-deferred withdrawals with tax-free withdrawals to maintain your desired tax rate.

- You generally want to spend taxable money before tax-protected money in retirement.

- Even those seeking an early retirement should still max out retirement accounts rather than investing preferentially in a taxable account.

- Retiring early may bring you tax deductions—especially child-related tax deductions—that doctors never qualified for during their working years, due to their high income.

- No payroll taxes are due in retirement because they are only collected on earned income.

- It is entirely possible to spend six figures each year without paying any income tax at all, and you don't have to buy any “special” insurance products to do that.

What is the take-home message for you? Do these analyses make you more or less likely to consider an early retirement? How likely is it that the tax code will remain largely intact by the time you are ready?