By Dr. Jim Dahle, WCI Founder

By Dr. Jim Dahle, WCI FounderSome financial concepts are simple, but people make them complicated by not following directions well. The classic example is the Backdoor Roth IRA process. I'm constantly amazed at how many ways people can screw up what I find to be very straightforward. Other concepts are simply common dilemmas where reasonable people can disagree. The classic example of this is the almost ever-present Pay Off Debt vs. Invest question. However, sometimes personal finance really is complicated. Einstein supposedly said, “Make everything as simple as possible, but not simpler.” The most complicated routine question for investors is the nearly annual dilemma about Roth contributions and conversions. Neophytes don't realize how complicated it is. They pop into a forum or Facebook group and ask:

- “Should I make Roth or traditional 401(k) contributions?” or

- “Should I do a Roth conversion?”

as if there is a right answer to these questions. Sometimes they throw in a few numbers they think will help the forum members make a determination, but almost universally, they have no clue just how complicated and difficult this decision is. Even if we had ALL of their numbers, attributes, and attitudes listed, we might not answer their question accurately. Often, their question does not have an answer that is yet knowable.

It's Complicated

To make matters worse, lots of people fail to follow Einstein's advice and try to make it “simpler.” I had this happen when I was speaking to a group of surgeons. There was a financial advisor heckler in the audience who piped up during the Q&A period—not with a question but with an argument that pretty much boiled down to “Roth is always better.” That's obviously nonsense. Like fixing our ridiculous healthcare system problems, if you think the solution to the Roth contribution/conversion dilemma is easy, you don't understand the problem. There are all kinds of calculators out there to help you. However, if your assumptions do not match those of the calculator, its calculations are worthless to you. It's truly a garbage in, garbage out process.

In today's post, I'm going to try to provide some clarity on this issue, where clarity can be provided. Which is a minority of cases. I'm sorry. That's just the way it is. And the more time you spend thinking about this, the more you'll realize that I'm right about it. The good news is that you're not choosing between good and bad. You're choosing between good and better. Even if you make the wrong decision, any money put into retirement accounts is usually a pretty good thing for most people.

But the reason this post is more than 4,000 words long (and likely to grow in the future) is because this is really, really complicated. Just recognize that up front.

The Contribution Question Is the Same as the Conversion Question

The first thing to realize is that we're not talking about two separate things here. If it makes sense to make Roth contributions, it probably makes sense to do Roth conversions and vice versa. The factors that go into these decisions are the same.

More information here:

Should You Make Roth or Traditional 401(k) Contributions?

Roth vs. Tax-Deferred: The Critical Concept of Filling the Tax Brackets

Does a Roth Conversion Count as a Contribution?

Another thing to realize is that there are no limitations on the amount of Roth conversion that can be done. You can literally convert a billion dollars in one year if you want. There a re limitations on retirement account contributions each year though. For example, in 2025 somebody under 50 can contribute $23,500 of earned income as an employee contribution to a Roth 401(k).

The No-Brainers

The next thing to realize is that this isn't always a dilemma. Sometimes, it's a no-brainer. When I was in the military, for example, our retirement plan was the Thrift Savings Plan. There was no option for Roth contributions back then. It was tax-deferred or nothing. The tax-deferred vs. Roth contribution question was a no-brainer. I made tax-deferred contributions.

Another example of a no-brainer is the Backdoor Roth IRA process. When you understand this process, you realize your options are:

- Invest in taxable

- Invest in a non-deductible traditional IRA, or

- Invest in a Roth IRA

That's a no-brainer. No. 3 essentially always wins. Of course you're going to do the Roth conversion (assuming no pro-rata issue).

Another no-brainer is the Mega Backdoor Roth IRA process, done with a 401(k) or 403(b) that allows after-tax employee contributions and in-plan conversions. It's not a tax-deferred vs. Roth question. There is no cost to the conversion, so of course you should do it.

There are no Roth defined benefit/cash balance plans, so tax-deferred contributions there is a no-brainer.

If you're a non-traditional medical student with a bunch of tax-deferred accounts from your prior career, doing Roth conversions at a tax rate of 0% in the first couple of years of med school is a no-brainer. Get them done. Any time you're in a 0% bracket, do just as many Roth conversions and contributions as you can. It's a no-brainer.

I'm sure there are a few other no-brainers out there. If you can think of another, comment on the post and I'll add it to the list.

Rules of Thumb When Deciding Between Roth Contribution or Conversion

Everybody wants a rule of thumb. Everybody wants to make it simpler than it is. Those of us who work in personal finance try to do this. I've got my own rule of thumb about Roth contributions/conversions. It goes like this:

“If you're in your peak earnings years, make tax-deferred contributions. In all other years, make Roth contributions (and conversions).”

As you might expect, this rule of thumb has plenty of exceptions—there might be so many that it isn't even useful as a rule of thumb. For example, a resident is not in their peak earnings years. Yet it often makes sense for them to make tax-deferred contributions to reduce income and, thus, Income Driven Repayment (IDR) payments and increase the amount of their federal student loans eligible for Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF). Another common exception is for those expecting a great deal of taxable income during retirement that will fill up the lower brackets that would “normally” be filled with tax-deferred retirement account withdrawals. This includes those with large pensions, investors with rental income from fully depreciated properties, and even supersavers with high seven- and eight-figure tax-deferred accounts.

Be careful of rules of thumb. Like the calculators, they're garbage in, garbage out.

The Biggest Factor for Roth or Tax-Deferred Retirement Account Contributions

The most important factor when it comes to deciding whether to make Roth or tax-deferred retirement account contributions or whether/when/how much to do Roth conversions is this:

It is VERY important you understand this concept. It is far more important than anything below this section in this blog post. Some people mistakenly think that the secret is to avoid paying large amounts of taxes. When it comes to making these decisions, it really doesn't matter how much you pay in taxes or when. What matters is which choice results in more money AFTER the taxes are paid.

A dumb rule of thumb you might hear occasionally is, “Pay taxes on the seed, not the harvest.” For example, if you're putting $10,000 into a retirement account, they're saying you should pay the taxes now (let's say 30%, or $3,000) because, in 30 years when that $10,000 has grown to $100,000, you'll owe $30,000 instead of $3,000 in taxes. And since $30,000 > $3,000, that must be dumb. Nope. It turns out it doesn't matter. If you pay $3,000 now, your $7,000 grows to $70,000. If you don't pay $3,000 now, your $10,000 grows to $100,000 and then you pay $30,000 in taxes, leaving you with $70,000. Same same. So, focus on the tax rates, NOT the tax amounts.

Likewise, you need to think about who's actually going to spend this money (or withdraw it from the account). Here are some possible options:

- You in a higher tax bracket

- You in a lower tax bracket

- Your spouse in a higher tax bracket

- Your spouse in a lower tax bracket

- Your heir in a higher tax bracket

- Your heir in a lower tax bracket

- A charity

Perhaps the dumbest move out there is to do a Roth conversion on retirement account money that is going to be left to charity. If you leave the money to charity, the charity won't have to pay any taxes on it. If you were to do a Roth conversion and “pre-pay” the taxes on that account, all you're doing is deciding you would prefer to leave money to Uncle Sam instead of your favorite charity. Same problem with Roth contributions/conversions if you expect to withdraw that money at a lower marginal tax rate in retirement yourself or leave it to an heir with a much lower income than you.

On the other hand, if you're in the 12% bracket and leaving money to your doctor kid in their peak earnings years who is in the 35% bracket, the family would be much better off if you would prepay those taxes at 12% instead of having your kid pay them later at 35%.

This factor DWARFS all other factors in the list below. While you can't always predict these future tax brackets exactly, spend most of your time here when facing these Roth dilemmas.

More information here:

Why Wealthy Charitable People Should Not Do Roth Conversions

Split the Difference

If you just can't figure it out (or don't want to), there is an option for you. I call it “Split the Difference.” One of my partners has been doing this for his entire career. He has no idea if Roth or tax-deferred contributions to the 401(k) are best for him and his situation. He doesn't even want to think about it. So, he just splits them in half—half goes to Roth, half to tax-deferred. He knows that he is making the wrong decision with half his money. However, he also knows that he is making the right decision with half. He is aiming for regret avoidance.

One can do something similar with Roth conversions. You can just do a “small” Roth conversion every year between retirement and when you take Social Security, perhaps an amount up to the top of your current tax bracket. Maybe that's $30,000 or $100,000. It's probably never going to be your entire account and maybe you should have done more (or less), but you will have converted something, essentially splitting the difference in a reasonable way. The more time you spend thinking about all these factors, the more you may realize this approach isn't nearly as naive as it first appears.

Filling the Brackets

The concept of filling the brackets is also critical to understand. Let's say you retire at 63 in a tax-free state, have no taxable income (or assets) whatsoever outside of your tax-deferred account withdrawals, and file your taxes Married Filing Jointly (MFJ) using the standard deduction. You want to spend $150,000. What is the tax cost of that?

In 2025, the standard deduction is $30,000. That's essentially the 0% tax bracket. No tax is due on that $30,000. The next $23,850 gets taxed at 10%. That's $2,385 in tax. The next $73,100 gets taxed at 12%. That's $8,772 in tax. The last $23,050 gets taxed at 22%. That's $5,071 in tax. The total tax bill is $16,228.

That's $16,228/$150,000 = 10.8%. If you saved 32%, 35%, or even 37% on all of those contributions and are now paying 10.8% on the withdrawals, that's a winning strategy. This is why tax-deferred contributions are usually the right move during peak earnings years for most people.

Pensions and Other Taxable Income = Roth

On the other hand, many people DO have other taxable retirement income that fills up those lower brackets. Let's say we have a single person who spends their peak earnings years with a taxable income of $350,000 or so in 2025 dollars. That's the 24% bracket. They started investing in real estate early and used depreciation to shield all that income while they were earning and paying off those investment property mortgages. Now in retirement, the mortgages are gone but so is the depreciation. They have $50,000 in Social Security, a $100,000 pension, and $200,000 in fully taxable investment property income. Awesome! Income is good. The problem is that all of that income is filling up the lower brackets. Let's say they're a pretty big spender and want to spend $500,000 a year in retirement. That again is a $150,000 withdrawal from the tax-deferred accounts, the same as in the above example. At what tax rate will that money be withdrawn?

The answer is 35%. Social Security (85% of which is taxable) filled up the standard deduction, 10% bracket, and a big chunk of the 12% bracket. The pension and real estate income filled up the rest of the 12% bracket along with the 22%, 24%, 32%, and part of the 35% bracket.

This investor contributed to these tax-deferred accounts at 24%, but they are withdrawing at 35%. Roth contributions/conversions, at 24%, 32%, or even 35%, would have been smarter. Income from something like a Single Premium Immediate Annuity (SPIA) has a similar effect as it is essentially a pension you buy from an insurance company.

Note that a huge taxable account does not necessarily change this calculus, at least if invested tax-efficiently. This is because qualified dividends and long-term capital gains “stack on top” of ordinary income. Tax-deferred account withdrawals are always ordinary income, and they are minimally affected by the taxable account.

Long Widowhood (Widowerhood) = Roth

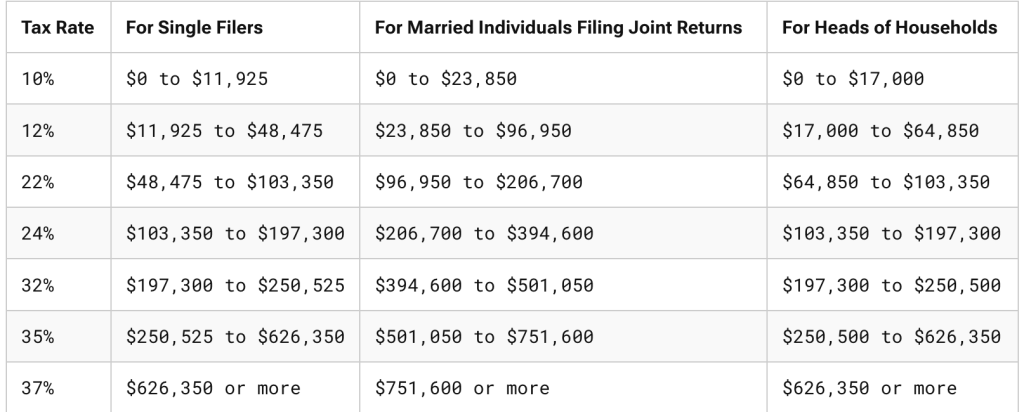

The astute observer will notice that I changed more than one variable in the above example. Not only did I fill the lower brackets, but we changed from the MFJ to the single tax brackets. If you haven't noticed, they're quite different. Here's what they look like in 2025.

As sad as it is to think about, many people who accumulated money while filing MFJ actually spend most of the money while filing single. If your spouse dies, your income usually falls a little bit (Social Security and possibly pension/annuity income decreases), but typically it is nowhere near cut in half. That's good, because your expenses aren't usually cut in half either. The property taxes, utilities, and transportation costs don't change much, and often, costs go up as you need to pay for more assistance without your spouse.

But the really big increase in expenses is probably taxes. Let's say you had a $300,000 taxable income before the death. That's the 24% bracket. Let's say the income falls to $260,000 after the death. That's the 35% bracket. Roth contributions and conversions that might not have made sense for retirees expecting to be in the 24% bracket may very well have made sense for a retiree in the 35% bracket. Like many factors, this one is unknowable without a functional crystal ball, but the larger the age gap and health gap between spouses, the more consideration should be given to Roth contributions and conversions.

“Gray” divorce is a similar issue people worry about. However, income and assets DO usually get cut in half with divorce, unlike death. If your income goes from $300,000 to $150,000 with divorce, you'll still be in the 24% bracket.

More information here:

Preparing for Tragedy: Ensuring Your Partner Can Manage Without You

What to Do If Your Doctor Spouse Dies Young

Changing States

So far, we have only been discussing federal income tax rates. For most of us, our marginal tax rate also includes a state tax rate. But even without legislative change, that rate could change significantly if we move. Many retirees spend their accumulation years in one state (such as New York) and their retirement years in another state (such as Florida). Well, New York has a rather onerous state income tax (6%-9.65% for most WCIers) plus the NYC city tax of 3%+, but Florida does not have an income tax at all.

This sort of planned move would argue against Roth contributions and conversions. On the other hand, if you're planning to move from Alaska (0%) to Oregon (4.75%-9.90%) for retirement, you should give some extra consideration to Roth contributions/conversions.

Source of Funds Matters, But Not Too Much

When doing Roth conversions, it is best if you can pay the tax on the Roth conversion from money outside the retirement account. This allows as much money as possible to stay in the retirement account where it can continue to grow in a tax-protected and asset-protected way. Even if you have to realize long-term capital gains to pay the tax bill, it is usually still better than paying the taxes from the retirement account. However, if a Roth conversion makes obvious sense when paid for with outside funds, it probably still makes sense when paid for with internal funds.

This is related to one reason why, when your tax bracket at contribution and withdrawal is equal, you should probably do Roth contributions. That's because $10,000 in a Roth account is the same as $10,000 in a tax-deferred account PLUS $3,000 in a taxable account. The taxable account will grow slower due to the tax drag from dividends and distributed capital gains. The entire Roth account will grow tax-protected. When anticipated tax brackets are equal, or even close, lean toward Roth contributions and conversions.

Behavior Matters

Another factor arguing for Roth contributions and conversions is investor behavior. Investors think $23,500 in their traditional 401(k) is the same as $23,500 in their Roth 401(k). It obviously isn't on an after-tax basis. The investor just spent the difference if they used the traditional 401(k). Sometimes you can fool yourself into saving more for retirement (on an after-tax basis) by using Roth accounts. That's not such a bad thing, given that most people are undersaving for retirement. I suppose the opposite could be an issue for a natural saver, though, so be careful with this one.

Asset Protection = Roth

Asset protection law is all state-specific, but as a general rule, retirement accounts get excellent protection and ERISA accounts (like your employer's 401(k)) are protected from bankruptcy in every state. When you do Roth contributions and conversions, you're getting more money—at least on an after-tax basis—into these asset-protected retirement accounts. If this is a big concern for you, this should push you in the Roth direction.

Not Spending RMDs = Roth

There is way too much fear out there about Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs). Frankly, most people should probably just spend their RMDs or give them away (especially as Qualified Charitable Distributions [QCDs]). The amount of dumb financial moves people have made due to RMD fear is legion, including pulling money out of retirement accounts early, never putting it in there in the first place, buying whole life insurance, trying to lose money, deliberately seeking out low returns, and more. But if you're truly in a position where you don't even want your RMDs and won't be spending them anyway (i.e. just reinvesting them in taxable), this should push you in the Roth direction since Roth accounts do not have RMDs.

Student Loan Games = Tax-Deferred

There are lots of “games” that can be played with federal student loans, including student loan holidays, forgiveness programs, income driven repayment programs, and interest rate subsidies. It seems these rules are all constantly changing, but the bottom line is that most of them determine your benefits using your income, specifically your Adjusted Gross Income (AGI). The lower your AGI, the lower the payments you make in IDR programs and the more that is left to forgive in forgiveness programs like PSLF. You know what lowers your AGI? That's right, tax-deferred retirement account contributions. For this reason, lots of docs—including residents, fellows, and new attendings—often make tax-deferred contributions when everything else suggests Roth contributions and conversions would be a smarter move. You have to weigh the student loan benefits against the tax benefits.

If you need help doing this, consider booking an appointment with StudentLoanAdvice.com.

More information here:

Roth vs. Traditional When Going for PSLF

Healthcare Costs = Roth (But Not Now)

Before age 65, lots of retirees purchase health insurance on an Affordable Care Act exchange. They often qualify for a substantial subsidy to help them pay for that. The amount of the subsidy is determined by the Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI, very similar to AGI). Doing Roth conversions that year decreases your subsidy, but avoiding tax-deferred withdrawals that year increases it. If you're still working, tax-deferred contributions can help, too.

Starting at age 65, most retirees sign up for Medicare. Well, if your MAGI (specifically your MAGI from two years prior) is too high, you have to pay an additional premium/tax for your Medicare benefits. This is called Income Related Monthly Adjustment Amount (IRMAA). Again, doing Roth conversions or withdrawing from a tax-deferred account (two years prior) increases your MAGI and your IRMAA cost. If you're still working, tax-deferred contributions can help, too.

Military Docs = Roth

Most military will soon exit the military and see their taxable income skyrocket. This is due to a higher income, no longer “officially” living in a tax-free state (as many military members do), and the loss of tax-exempt earnings while deployed and tax-exempt allowances. They should generally make Roth contributions and convert anything they can. Even if they stay in and eventually qualify for a pension, they should still do Roth since that pension will be filling up the lower brackets.

Optionality = Tax-deferred

A nice benefit of making tax-deferred contributions now (or not doing a Roth conversion now) is that you retain the option to do a conversion later, potentially at a much lower tax rate. That optionality has value.

Supersavers = Roth

The more you save for retirement, the more you'll have in retirement. That usually means the more tax you'll pay in retirement. Thus, the more you save, the more likely you are to benefit from Roth contributions and conversions for that money you'll spend in retirement. If you save a lot of money in tax-deferred accounts, it's entirely possible to actually have a true “RMD Problem.” I define this as having a higher tax rate on your RMDs than you saved when you were contributing the money.

Let's consider a couple that makes $500,000 a year but puts $70,000 into his solo 401(k), $80,000 into his defined benefit/cash balance plan, $30,000 (with match) into her 403(b), and $23,500 into her 457(b). That's $203,500 per year in tax-deferred contributions. If they do this for 30 years and earn a real 5% on it, that'll add up to

=FV(5%,30,-203500) = $13,500,000

The RMD on that at age 75 will be about $541,000 in today's dollars. That'll get them all the way into the 35% bracket even without any other taxable income or one of them becoming a widow or widower. And those RMDs will double by the time they're 90. Yet during their peak earnings years, they were only in the 24% bracket. If you're really putting a ton of money into retirement accounts every year and you plan to work and save for a long time, you should consider doing Roth contributions and conversions along the way, especially if it is you who will be spending that money later. This might not be as necessary if most of that tax-deferred money will go to charity or a lower tax bracket heir, of course.

High investment returns also have a similar effect to being a supersaver. Of course, it's generally easier to predict your future savings behavior than your future investment returns.

More information here:

Supersavers and the Roth vs. Tax-Deferred 401(k) Dilemma

Rising Tax Brackets = Roth

Some investors are absolutely convinced the US government will be raising the tax brackets substantially in the future. This isn't as big of a deal as most of these people fear. They'll still be pulling most of their tax-deferred money out at lower tax rates even if every tax bracket goes up 3%, 5%, or even 10%, which would be a huge increase in taxation. But that is a factor that should lead one to make more Roth contributions and conversions. But if you think the US government is going to melt down or disappear altogether, you might as well get your tax breaks while you can with tax-deferred contributions and avoid conversions.

Early Retirees = Tax-deferred

The earlier you retire, the more likely making tax-deferred contributions now will work out well for you. Not only does that mean less time to save up a huge nest egg (so not as much of a supersaver issue) and more years to do Roth conversions later, but there are a few other things too. For example, while you can withdraw Roth contributions tax and penalty-free prior to age 59 1/2 using the Substantially Equal Periodic Payments (SEPP or 72T) rule, the earnings are taxable before age 59 1/2. They were already going to be taxable for tax-deferred contributions, but you lose a big benefit of Roth accounts for that money. (Although to be fair, most early retirees have relatively large taxable accounts and perhaps a 457(b) account and often enough Roth contributions to get them to age 59 1/2 anyway). There is also less guaranteed income in early retirement (this is pre SS years and few buy SPIAs that young). Early retirees were also generally higher income earners to be able to save all that money up, so there is likely a relatively larger arbitrage between their marginal tax bracket while working and in early retirement.

Heirs That Don't Know About IRD = Roth

If you end up being so wealthy that your estate has to pay estate taxes, your heirs can get a tax break on inherited tax-deferred IRA withdrawals they take. This is generally referred to as Income with Respect to a Decedent (IRD). But lots of heirs and their advisors and accountants may not know to take this deduction. If you want to eliminate their need to know about this, you can do more Roth contributions and conversions.

Current Mix of Accounts

The Roth contribution/conversion decision also relies a bit on what you already have. Tax diversification can be handy in retirement. If all your current retirement money is Roth, then you should give more consideration to some tax-deferred contributions. If almost all of your current savings are tax-deferred, Roth contributions and conversions are likely a little more valuable to you than if you've already got a 50/50 mix.

Phaseouts

Unfortunately, there is more to your marginal tax rate than just tax brackets. There is more to your marginal tax rate than your tax bracket and your ACA subsidy or IRMAA premium. In fact, there are all kinds of phaseouts in the tax code where your marginal tax rate can get very high over a pretty narrow range of income. If your income is expected to be in or near one of those ranges, that provides a compelling argument for tax-deferred contributions (in the accumulation phase) or tax-free withdrawals (in the decumulation phase).

College Aid

The children of most WCIers aren't going to qualify for any need-based aid due to the high income and high assets of the family. But if your children are, then retirement account decisions can affect that number. During the accumulation years, tax-deferred contributions lower your income. Retirement account money isn't counted toward your Student Aid Index (SAI), so if your retirement/taxable ratio is larger due to Roth contributions and conversions, that's a good thing. During decumulation years, tax-free withdrawals help keep your SAI lower.

Don't Beat Yourself Up

As you can see, there are a plethora of factors that affect the Roth contribution/conversion decision. It's not even close to easy to decide much of the time. Many relevant factors are currently unknown and probably unknowable (your future income, future returns, future tax brackets, future RMD rules, future family situation, the tax brackets of your heirs, etc.). You're not going to get this right every year. You'll blow it a few times. That's OK. Give yourself some grace. Sometimes it works out fine.

For example, when I was in the military in a low tax bracket, we made tax-deferred contributions to the TSP. There was no Roth TSP available anyway. But we didn't convert it all to Roth the year I left the military. I thought for many years that was a mistake. However, now it appears that we'll be leaving more to charity than we have in tax-deferred accounts, so it'll work out fine in the end. We didn't make a mistake after all.

Remember that you're choosing not between good and bad but between good and better.

What do you think? What factors did I forget? What else went into your calculus when making this decision?