By Dr. Jim Dahle, WCI Founder

By Dr. Jim Dahle, WCI FounderInvesting is far more about risk control than it is about seeking returns. Wise investors take the minimum amount of risk necessary to reach their financial goals. Don't risk money you don't have to get money you don't need to impress others who you don't care about.

However, you can't spend (or eat) risk. Returns spend the same if you took a lot of risk or not. A great way to run out of money is to not take on enough risk in a portfolio to ensure real (after-inflation) growth of your assets. While there is a general correlating relationship between risk and return (more risk = more return), there is plenty of risk out there that is never rewarded. The classic example is the uncompensated risk of investing in individual stocks. If a risk can be easily diversified away (as individual stock risk can be), why would you expect to be rewarded for taking it?

Risk-Adjusted Returns

The concept of risk-adjusted returns is important to understand. You want the best returns you can get for any given level of risk. While methods of calculating returns are relatively standardized and agreed upon, risk is far harder to measure. The easiest measurement of risk is simply the probability of an outcome vs. its impact. The higher the probability of a bad outcome and the worse its impact on your life, the riskier that investment is for you. For example, say you put all of your money into a brand-new cryptocurrency. Not only is it highly likely to go bust, but if/when it does, it will have a massive impact on your financial life.

The actual risk of most investments is extremely difficult to measure. The true risk is permanent loss of capital, aka “deep risk,” and Bill Bernstein divided it into:

- Inflation

- Deflation

- Confiscation

- Devastation

Novice investors, however, are far more focused on “shallow risk,” aka volatility. While the true likelihood and impact of the deep risks are unknown and unknowable, volatility is readily measured, at least in the past. Thus, most risk-adjusted returns use the return and adjust it for volatility using some sort of volatility measure.

More information here:

How to Think About Risk and Why It’s So Hard to Quantify

Sharpe Ratio

In 1966, William Sharpe came up with the Sharpe Ratio (aka the Sharpe Index or Sharpe Measure) as part of the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM), and it has been widely used since to provide “risk-adjusted returns.” The Sharpe Ratio is simply the return of the investment minus the “risk-free return” (i.e. that return provided by a cash investment such as Treasury bills) all divided by the standard deviation. All else equal, a higher Sharpe Ratio is better, and Sharpe Ratios over 1 are considered quite good. A negative Sharpe Ratio means the investment underperformed cash. Theoretically, if you borrow to invest in something with a positive Sharpe Ratio, you should come out ahead over the long run.

If you achieve a 10% return from your stock market investment and cash is paying 4% and the standard deviation of the market is 15%, then your Sharpe Ratio is (10% – 4%)/15 % = 0.4. When I wrote this, per Morningstar, the Sharpe Ratio for the Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund over the last decade was 0.75. That doesn't seem all that good until you compare it to some alternatives. The riskier (and lower performing over the last 10 years) Vanguard Small Cap Value Index Fund had a Sharpe Ratio of 0.56. The REIT Index Fund had a Sharpe Ratio of 0.39. The Total Bond Market Fund had a Sharpe Ratio of 0.06 over that same 10-year time period.

Using various asset classes with high returns and low correlation in a portfolio can lower the portfolio's volatility and, thus, increase its Sharpe Ratio. An investor should not care about the performance of the individual asset classes in the portfolio but only about the overall performance.

Treynor Ratio

The Sharpe Ratio is not the only way to risk-adjust returns. The Treynor Ratio uses “beta” in the denominator instead of standard deviation. Beta measures systematic risk, i.e. market risk. The weakness of the Treynor Ratio is that it can make an undiversified portfolio look better than it actually is. However, when a portfolio is appropriately diversified, a Treynor Ratio is considered more useful than a Sharpe Ratio.

Sortino Ratio

Yet another measure of risk-adjusted returns is the Sortino Ratio. The Sortino ratio only uses downside deviation to adjust its returns. Its creators correctly figure that nobody minds upside volatility.

More information here:

Yes, Risk Tolerance Can Be Modified: You Just Have to Rewire Your Brain

Criticisms of Risk-Adjusted Returns

There are a number of problems with risk-adjusted returns. While useful in theory, the idea in practice breaks down significantly for several reasons.

#1 Nobody Cares About the Past

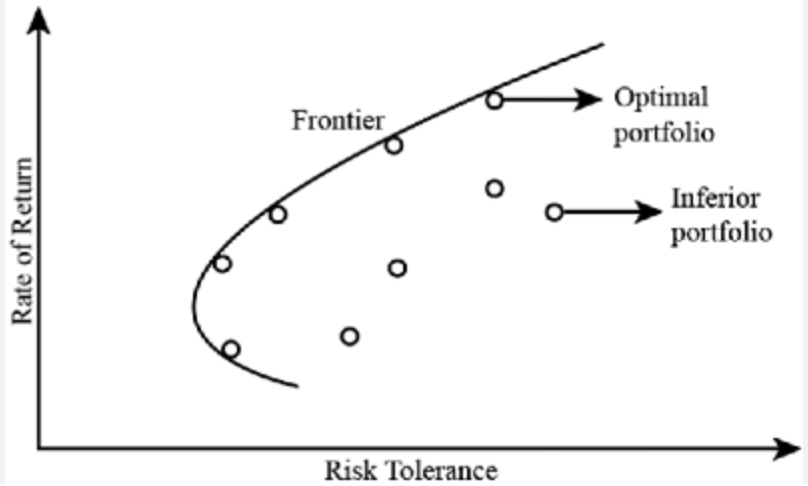

You can only accurately calculate any of these ratios for the past. While you can use projected returns and projected volatility, your cloudy crystal ball is only so accurate. The underlying assumption here is that the future will at least resemble the past and that is not necessarily accurate, especially when only looking at short time periods (a decade or less) in the past. A similar situation exists with the “Efficient Frontier,” which can also only be known retrospectively.

#2 Distributions Aren't Normal

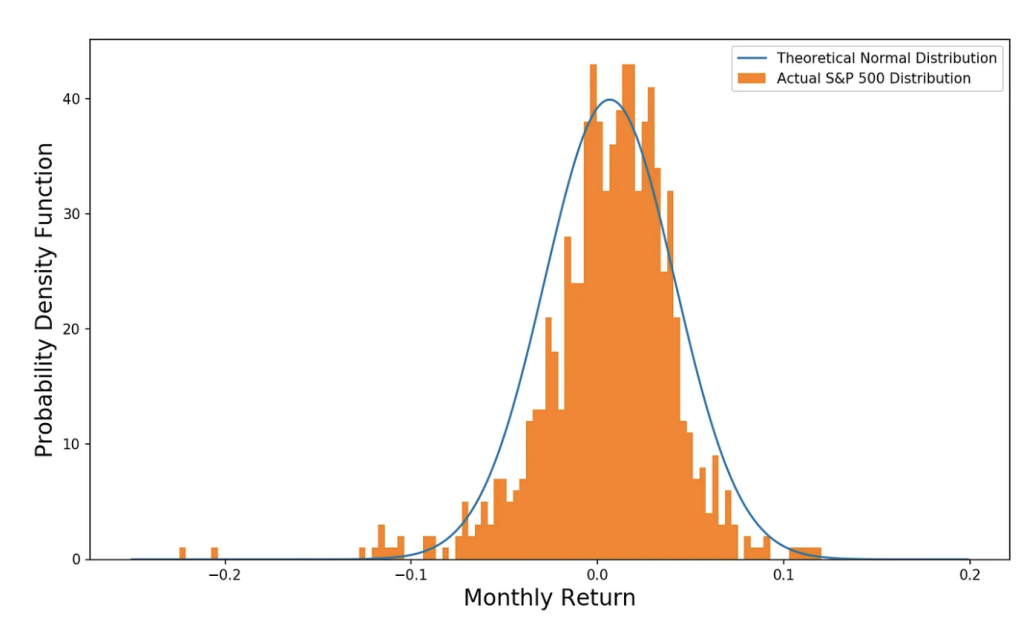

Statistically speaking, the Sharpe Ratio assumes that distributions are normal. Well, they aren't. They have “fat tails,” meaning that rare events, both positive and negative, are more common than they would be in a normal distribution. Essentially, the market is more volatile than you would think given its standard deviation. The longer the time period, the less normal stock market returns become. On a monthly basis, they look mostly normal in this chart by Tony Yiu.

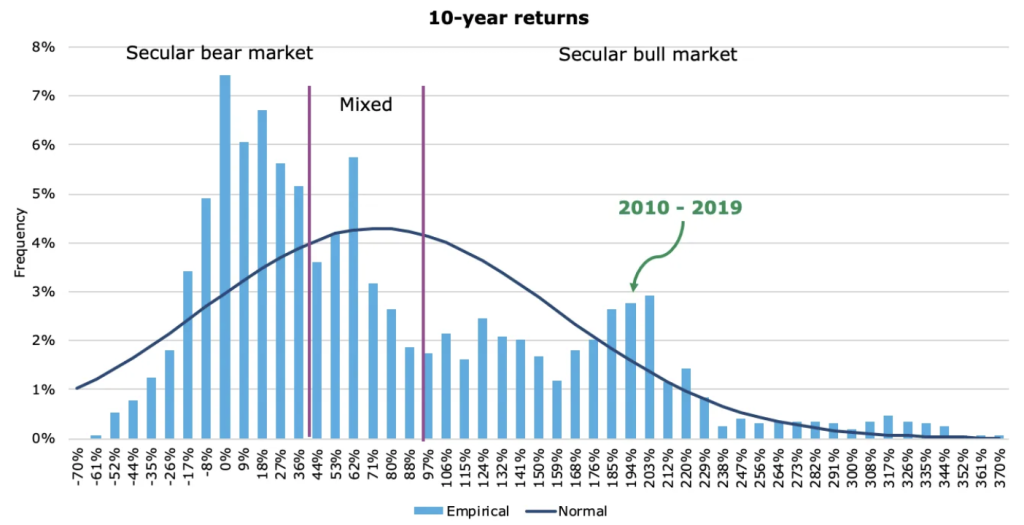

But consider the work of Joachim Klement, who also looked at three- and 10-year returns.

#3 It Measures a Risk You Shouldn't Care About

All of these measures use volatility as a proxy for risk. The risk I really care about over my long investment horizon is not volatility. I'm perfectly fine with volatility. In fact, volatility affords me numerous opportunities during my career to buy low. While lowering volatility might help me sleep better at night, it probably won't do much for the eventual outcome. Avoiding and minimizing the effects of deep risks, as difficult as that might be, seems a much better place to spend my energy.

#4 It Fails for Investments That Are Infrequently Marked to Market

Private real estate has been shown to be less volatile and has a better Sharpe Ratio than public real estate, such as REITs traded on the stock market. However, part of that may simply be a function of the difficulty of measuring the volatility of a non-traded asset. Is it really less volatile, or is the volatility just hidden by the fact that the property is only appraised once a year or less?

While the concept of adjusting your returns for risk is a worthy endeavor, the actual tools to do this leave us short. Be careful when somebody trots out risk-adjusted returns in an attempt to convince you to invest with them—especially when the investments, asset classes, and portfolios being compared are not similar.

What do you think? How do you use Sharpe Ratios and other measurements of risk? Do you try to “risk-adjust” your returns? Why or why not?