Years ago, people worried about the rapidly escalating cost of a college education. So, parents started saving. Even the government got involved eventually with the creation of Coverdell Education Savings Accounts and 529s. That all seems so Boomer now—or at least Gen X. The housing crisis in our country makes the task of coming up with $100,000 or even $300,000 to pay for your child's education seem downright trivial.

Salt Lake County, where I call home, is far from the high-cost-of-living areas (HCOLAs) of the Bay Area, Washington DC, Boston, LA, or Manhattan. Yet the median cost of a home purchased in Salt Lake in July 2025 was $589,500. The median household income in Salt Lake County was $94,658. How much income does somebody need to afford the median house? Assuming they can somehow come up with a 20% ($117,900) down payment, my 2X rule (mortgage should be no more than 2X gross income) would suggest an income of ($589,500-$117,900)/2 = $235,800. The median salary for a dentist in 2024, per the Bureau of Labor Statistics, was $179,210. The ADA says it is $218,710. But either way, your child's household income will need to be higher than that of a dentist—at least an associate dentist—for them to afford the median home in my county. And forget it if you want a home where your kids go to a well-regarded school. Those are mostly seven-figure homes.

This is particularly true now that we live in a world with normalized interest rates. At 6.5%, a 30-year mortgage of $471,600 is over $3,000 a month ($36,000 per year), not including property taxes or insurance.

The children of most WCIers will earn less than their parents on an inflation-adjusted basis. The only way they're going to have the ability to buy the median home in many geographic areas—much less a home comparable to the one they grew up in—will be with parental help. Thus, many WCIers are very interested in assisting their children with home ownership. This is not necessarily a bad thing. As Bill Perkins famously pointed out in his personal finance insta-classic Die with Zero, an inheritance between 25 and 35 is far more useful than one received at age 60. This post will discuss the pluses and minuses of the various methods to assist them.

Before we get into the list, however, I think it is worth spending a minute pointing out that it is best to help others from a position of strength. I often run into parents who start 529s for their kids before they ever pay off their own student loans. Likewise, it seems a bit silly to start saving for your child's house before you have even paid for your own. It is much easier, both cash-flow wise and behaviorally, to save for “extras” like helping others when you no longer have any payments of your own. Just like your child can get a loan for their education (or choose a cheaper school), your child can get a mortgage (or buy a cheaper house), but nobody is going to loan you money on which to retire. If you want to help others, help yourself first. Although cultures vary, I think it's a little rude to help your child buy a home expecting that there will be a little room in it for you to live out your last couple of decades.

10 Ways to Help Your Child into a House

Here are 10 different methods to help your child with their housing costs, along with the pros and cons of each.

#1 Invite Them into Your Home

A commonly used method is to simply let your child live with you. It is very common these days for college students and even college graduates to still live at home, even if they're employed and otherwise making progress in life. Not to mention the “classic” 29-year-old son playing video games in the basement 14 hours a day. Even in a married-with-children scenario, living in the basement for a few months while saving up a down payment can be very helpful. The length of this arrangement is highly variable, but I suppose it is even possible to live together until the death of the parent, so the child could inherit the house.

While I wouldn't want to live with my parents, it's hard to argue that this is not a very cost-efficient (and tax-efficient) method. The cons, besides having to live with your parent(s), include the possibility of getting evicted over your refusal to eat your carrots or some other silly thing. If you assumed you were going to live there for a much longer time period, perhaps you had not saved up enough to ever live your desired lifestyle independently.

#2 Leave Them Your Home

A very tax-efficient way to help your child with housing is to leave them your home upon your death. Not only do they get a home, but they get a step up in basis, so if they wanted to sell it, neither party has to pay any capital gains taxes on it. While capital gains taxes paid on occupied homes used to be pretty rare, that $250,000 ($500,000 married) exclusion is much more commonly reached these days due to the housing crisis and the fact that it was never indexed to inflation. It doesn't apply if you die and they inherit the home, though. The major downside to this approach? Your kid will probably be 60 or so by the time you die. Who wants to wait until then to own a home?

More information here:

How to Buy a House the Right Way

#3 Co-Sign for Their Mortgage

One of the dumber ways to help your children get a home is to co-sign for their mortgage. The lender not only considers their income and assets but also yours. This makes it much more likely for them to qualify for a mortgage so they can get into a house that can start appreciating and so they can stop “throwing money away on rent.” The problem is that you've helped them buy a home they can't actually afford. Mortgage lenders have guidelines for a reason, and they're pretty reasonable. More than reasonable, actually. If you're borrowing as much as a lender will give you, you're probably buying too much home. If you're borrowing even more than a lender will give you (because you're using a co-signer), you're definitely buying too much home. Unless something changes in your future (a dramatically higher income, a big inheritance, or some other windfall), there's a good chance this won't end well.

I speak from experience on this. Katie's parents co-signed for our first home, a condo we bought as I started medical school. We sold that $80,000 condo for $83,000 four years later, but we lost money on it due to the transaction costs. We had no business buying a home at that stage of our lives, but somehow the four of us all bought into that famous realtor/bank-driven marketing about the American Dream and throwing money away.

The biggest issue with co-signing for a loan is when things go badly. When your kid stops paying the mortgage, you're legally on the hook for it. Your credit score will tank, and you'll end up in court eventually if you don't start paying the mortgage on their behalf. Now, everybody has a foreclosure on their record.

Just don't do it. My in-laws got lucky. We scraped together our mortgage payments and all the other expenses for four years, so it never cost them anything but the hassle of qualifying for a mortgage. But they took on risk they shouldn't have taken. If you want to help your kids buy a house, use one of the other methods on this list instead.

#4 Buy Them a House

Do you have a lot more than you need and really want to help your kids build wealth despite the housing crisis? Then just give them enough money to buy a house. Yup, the whole thing. A $700,000 house? Give them $700,000. The upside is they will never have a mortgage. Your grandkids will never be foreclosed and evicted. Maybe they'll even live a little closer to you than they could otherwise afford, so you can see those little darlings a lot more frequently. Imagine how fast you could build your own wealth if you never had a mortgage. That would be awesome, right? That's the opportunity you're now giving your kid. Obviously, you need to make sure the kid can afford the property taxes, insurance, utilities, furnishings, maintenance, and all the other expenses of home ownership, but that's a lot easier when you get rid of the principal and interest payments (ask me how I know).

What are the downsides? The first one is that $700,000 (or whatever) that you used to own is no longer yours. If you need that money later, you'd better hope your kid really did save and invest the difference and feels so grateful to you that they'll be equally generous with you.

Another significant downside may be the cost of liquidating that huge chunk of money. There might be commissions or other fees. There will probably be taxes (and maybe penalties, too, if you pull it out of a retirement account). Which brings us to option #4(a).

#4(a) Gift Them Appreciated Shares

Instead of selling your appreciated investments and giving them cash, why not give them appreciated shares like you would to charity? While their tax bracket isn't 0%, it's probably lower than yours. Better for them to pay capital gains taxes at 0% or even 15% than for you to pay them at 23.8%.

Now, let's continue on with the long list of downsides of giving your children enough money to buy a home. One of the biggest concerns was discussed in that 1990s personal finance classic The Millionaire Next Door in a chapter called Economic Outpatient Care. Basically, the idea was that people who get a lot from their parents, especially if they get money every year to live a higher-level lifestyle than they can afford, don't do a very good job of building wealth. There's more nuance to it, but that was the general idea. If you give your kid $700,000 (or whatever), what is that going to do to their work ethic? How about their spending level and their savings rate and how they invest and their career decisions and their relationship decisions and more? You better believe it is going to have some effects, and it's unlikely that all (or even most) of them will be positive.

Another problem with a huge gift is that the IRS doesn't allow tax-free unlimited gifting to individuals. If they did, rich people would just give all their money away to their heirs on their deathbed and avoid any estate taxes. If you give someone more than $19,000 in a given year [2025 — visit our annual numbers page to get the most up-to-date figures], you have to file a gift tax return and start using up some of your estate tax exemption, currently $15 million ($30 million married) [2025]. If you're rich enough that you're considering giving your kid enough money to buy an entire house, you're probably rich enough to eventually have an estate tax problem and you'll need that exemption. Some states have lower exemption amounts than $15 million, too—some are as low as $1 million (cough, Oregon, cough), and sometimes the tax rate is very high (cough, Washington state, cough). It's best to look into it.

Most doctors won't ever be wealthy enough to have a federal estate tax problem, but most doctors aren't gifting houses to their kids either. What can you do to get around this gift tax return issue? That brings us to #4(b).

#4(b) Gift Shares of an LLC Every Year

Form an LLC (technically a family LLC since all members of the LLC are in the same family). Have the LLC buy the house. Then, you gift shares of the LLC equivalent to the gift tax exclusion each year until the kid owns the entire house. Now, I know that feels like it will take forever, especially if the house is appreciating faster than about $20,000 per year, but keep in mind that EVERYONE can give ANYONE that $20,000ish a year. You can give $20,000 a year to your kid, and so can your spouse. And you can give $20,000 a year to your kid's spouse. And so can your spouse. That's $80,000 a year without having to file gift tax returns. Over a decade or so, you should have the ability to gift your kid an entire house without ever having to file a gift tax return, much less use up any of your estate tax exemption.

A significant downside may be a higher interest rate since the main owner of the house, at least initially, is not living in it. Occupiers tend to get lower interest rates from lenders than investors do.

#4(c) Use a Trust

Another great option for gifting is to do it years in advance. If you have an irrevocable trust set up that lists your child as one of the beneficiaries and the trust is allowed to distribute money for the purchase of a home, it can do so without any gift/estate tax consequences to you. The gift/estate tax consequences came at the time you funded the irrevocable trust and don't apply to all the growth on that money in between “contribution” and “withdrawal.” Income taxes do apply, of course.

#4(d) Use Your Roth IRA

Another option is to take advantage of the list of IRA penalty exceptions. Normally, you cannot withdraw money from an IRA prior to age 59 1/2 without paying a penalty. However, one of the exceptions to that rule is that up to $10,000 of earnings can be withdrawn penalty-free if used for a “first-time home purchase” (defined as no home ownership in the prior three years except a mobile home or a home owned together with a former spouse). Plus, the principal of a Roth IRA can always be removed tax- and penalty-free. The additional downside is that the money is no longer in a Roth IRA growing in a tax-free, asset-protected way. You can't just take out whatever money you want from a Roth. The first money out is contributions, then converted amounts, and then earnings. Five-year rules may also apply.

#5 Help Them with a Down Payment

Most WCIers can't afford to gift their children an entire home, especially if it's a big family. Most of them probably can help a little with a gift. That “little” might be $20,000 or it might be $200,000. However much it is, there are plenty of ways to think about this.

#5(a) An Outright Gift

Just like you can cut them a check (or give them appreciated shares) for the entire house, you can do it for a 20% down payment or part of the down payment. A 20% down payment allows your child to get a better mortgage loan and avoid Private Mortgage Insurance (PMI). You're so nice to help them do that. The downsides are all the same for gifting them enough to buy the whole home, but perhaps you reduce the Economic Outpatient Care problem and the risk of you actually needing that money later.

#5(b) A Match

Maybe you can reduce the Economic Outpatient Care problem by employing a technique suggested to me by WCI COO Brett Stevens—matching their own down payment savings 4:1 (or some other ratio). If they save up $20,000, you gift them $80,000. If they save up $1,000, you gift them $4,000. This incentivizes them to save as much as they can as fast as they can.

#5(c) A Slowly Forgiven Loan

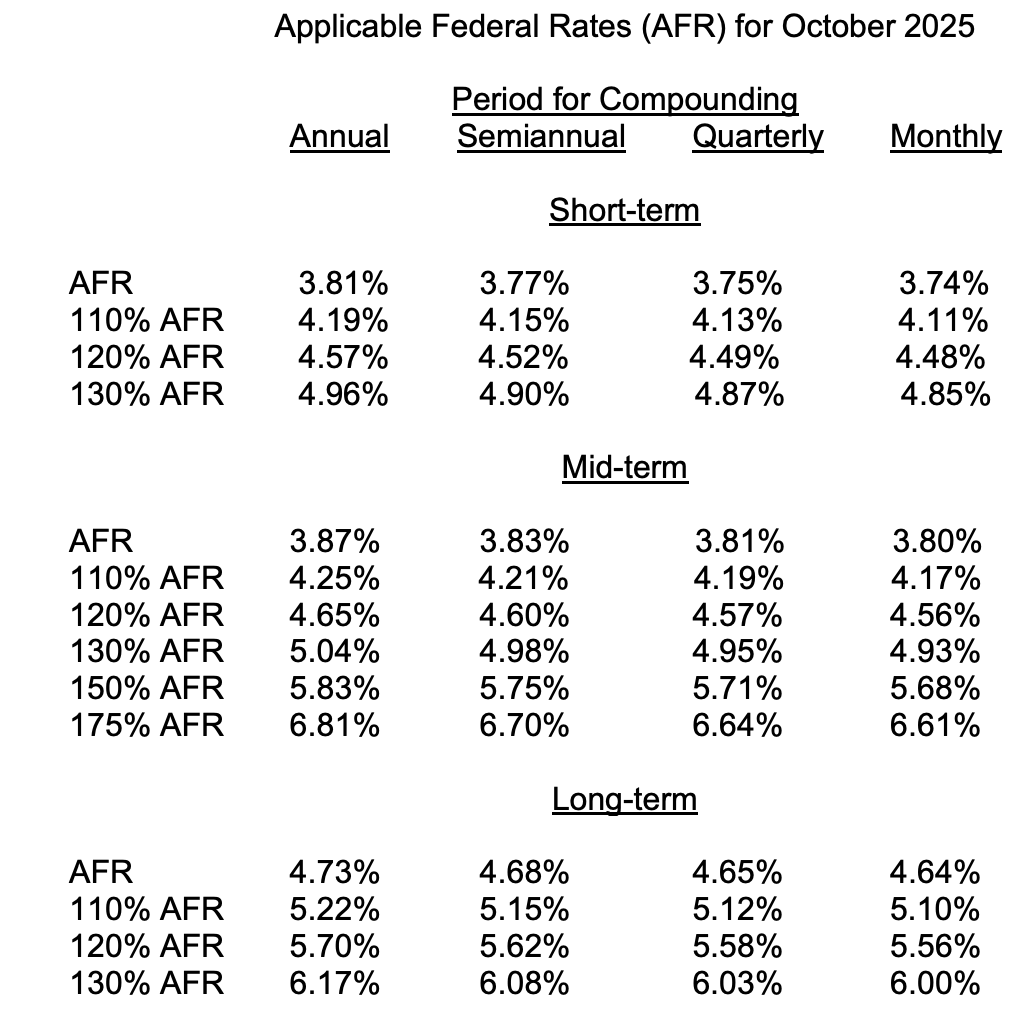

Another option to avoid using up your exemption or having to file gift tax returns is to loan them the money and then forgive the loan gradually using the annual gift tax exclusion amount. Note that when you loan a family member money, you can't just set the terms to whatever you want. The IRS has rules that apply to personal loans. You have to charge a specified interest rate, and you must pay taxes on that interest. These interest rates are known as “Applicable Federal Rates” (AFR), and whether you charge them or not, you'll pay taxes on them. As of October 2025, the rates looked like this:

Short term is less than four years; long term is more than nine years. This requirement to charge interest only applies to loans of $10,000 or more. The IRS will charge you taxes on the interest, whether it is actually paid to you or not. To make matters worse, unpaid interest above and beyond the annual gift/estate tax exclusion amount will require you to file a gift tax return and reduce your estate tax exemption amount.

The bottom line is that you can give your family member a better interest rate than the bank (4.7% beats 6.3%) but not dramatically better. You can use the gift tax exclusion amount to reduce the principal each year. Keep solid records of loan activity.

More information here:

#6 Use 529 Money to Help Buy a Home

Another unique strategy can be used if you have significant 529 accounts. While you cannot buy a home using 529 money (mortgage payments are NOT an approved expense), the parent can buy the home and the child can pay the parent rent using 529 money. At the end of college, the home equity generated can be gifted to the child. The downsides are all the same as those of just gifting them the money in the first place (plus some additional complexity), but it's possible you could get a little more money out of 529s tax-free this way. Be sure not to charge/pay more rent than the school's Cost of Attendance figures.

#7 Loan Them a Down Payment

Some parents have the means to loan their child some money for a down payment but not enough to gift it to them. You still have to charge them interest at the applicable AFR, and to make matters worse, many lenders do not allow for borrowed funds to count as a down payment. So, even if you gift them the down payment, it's best to do it a few months in advance so the lender doesn't ask too many questions about where that down payment really came from. If they find out that money really is a loan, the lender will likely charge you a higher interest rate for the mortgage, plus PMI, if they extend the mortgage at all. Yes, you can make the loan a few months in advance and try to hide it from the mortgage lender, but we generally refer to that strategy as “fraud.”

An additional downside of loaning your children money is that it changes the relationship. Dave Ramsey says that Thanksgiving dinner doesn't taste the same when you owe money to someone else at the table. I think that's probably true. What are you going to do if your children default on the loan? Are you really going to foreclose on the house? The house your grandbabies live in? Really? No. You're probably committing to gifting the money whether or not you can afford to do so. Don't loan more than you can afford to gift.

Thankfully, if you can't afford to gift them the money, you probably don't have an estate tax problem to worry about, so at least that eventual gift won't result in an additional tax.

#8 Be Their Mortgage Lender

Some wealthy families will just loan the entire mortgage to reduce the interest rate paid. This has all the same downsides as loaning them a 20% down payment multiplied by five. But if it all works out fine, the child gets a lower interest rate, the parents make about what they would have in a money market fund, and the financial and relationship risks all get swept under the rug. There is, of course, also the option to forgive all or part of the loan via gifts at any time. And if the loan is still there at the time of the parent's death, there hopefully will be enough of an inheritance left to pay it off. The child, of course, can refinance at any time and pay off the loan, too.

If you go this route, be sure to formalize the agreement and documents, and pay taxes on the interest earned. Both parties had better treat it like a real loan.

#9 Family Offset Mortgage

Here's another creative one I just learned about recently. This is known as a “Family Offset Mortgage” (FMO) or “Parent Offset Mortgage.” Basically, the child's mortgage is linked to a special bank account with the parents' cash in it. That cash functionally reduces the mortgage amount, lowering the loan-to-value ratio. That means the child borrows less for a home and has a lower monthly payment.

Imagine there is an $800,000 home, and you put $200,000 into the special linked account. The child now has a $600,000 mortgage. Cool, right? This will reduce the child's monthly payments or the term of their loan, but there is no gift made or gift tax return to worry about. Sometimes, the account still allows the parent to access some of their savings.

There are downsides, of course. The main one is that the parent is not paid interest for their savings. The interest rate on the loan probably isn't that great either. These are not yet widely available either, so you may end up having to keep cash in a bank that you otherwise would not use. If the parents do access the cash, the mortgage payment usually has to go up, and you usually can't access all of the money.

#10 Put Your Child's Name on the Title of Your Home

Want a dumber idea than co-signing for your kid's mortgage? Put their name on the title of your home. Then, when you die, it becomes theirs! Awesome, right? It's just like #2 above . . . except for that little step up in basis you no longer get. I can't think of any reason to put your kid's name on your title that is good enough to overcome that issue.

But what if you co-own the child's home? This is essentially 4(b) above, and it can be a method to slowly give them the home. Your share can even be left to them at the time of your death, and they would get a step up in basis on that portion.

More information here:

5 Ways to Set Up Your Kids Financially Without Ruining Them

The Worst Financial Gifts to Give Your Kids

Can You Rank the Options?

Some of these are obviously better than others. If I had to rank them from best to worst, I'd put them in this order:

- Use your trust to gift them a down payment or the entire home.

- Invite them into your home for a defined period of time to save up for theirs.

- Leave them your home if they're still struggling with buying one in late career.

- A match for their down payment savings.

- An outright gift toward their down payment (possibly using appreciated shares).

- Co-ownership via LLC with regular, defined gifts of equity.

- Family offset mortgage.

- A slowly forgiven loan of the down payment or the entire house.

- Use Roth IRA money as a gift or a loan.

- Be a long-term mortgage lender for part or all of the entire home.

- Use 529 money.

- Co-sign for their loan.

- Put their name on your title.

Reasonable people can disagree on the exact order, but try to avoid the bottom third of the list. It's OK to just say, “No.” Your parents didn't help you with your home, did they? And you made out OK. They probably will, too. Eventually. Hopefully.

What We Plan to Do

We haven't spent a lot of time talking about this, but we are considering some of the options near the top of the list. We already have a trust in place with most of “our” wealth, and the kids are all secondary beneficiaries of that trust. While our estate plan right now is a small 20s fund plus 1/3 of their inheritance at 40, 50, or 60, we're seriously considering modifying that to allow for an earlier distribution to be used to pay for part or all of a house. With both a 21-year-old and a 10-year-old, we don't know what that will look like exactly. But we probably still have a few years to figure it out. We worry about Economic Outpatient Care but hope we can overcome that issue with good financial education and teaching of character.

We like the idea of matching down payment savings. We've done matches before with their cousins in the 529s, but the only match our kids have ever earned is the 100% “parent match” into their Roth IRAs as teenagers for their jobs. But this reminds me of the school of thought that children paying for their college education with borrowed money is somehow good for them, even if the parents can afford to pay for it. I just don't agree with that. And we (well, the trust) can certainly afford to pay for some sort of reasonable home even at today's prices.

We're also sort of willing to let them come live with us for a short period of time. While I've told them they're moving out at 18 from the time they were 5 or so, their mother is a little more lenient, at least while they're on breaks from college. But after college, I've told them the deal. They can stay with us, but they have to pay rent. The rent is very reasonable ($100 a month) at the beginning, but it goes up $100 a month indefinitely. Eventually, they'll move out. Even Momma's cooking isn't that good.

If you're wealthy enough, start thinking about how you are going to help your children get into a home. This is a much bigger deal than it used to be, and it's now far more expensive than most educations.

What do you think? Will you help your children get into a home? How?