By Dr. Jim Dahle, WCI Founder

By Dr. Jim Dahle, WCI FounderAs I've gotten older, I've noticed a trend. Many doctors think there was a “golden age” of medicine where doctors made dramatically more than they make now. And when was the golden age of medicine? The actual dates of this supposed “golden age,” of course, are extremely variable. It always seems like the golden age ended 5-10 years before the doctor talking about it came out of training.

When I was in medical school in 1999-2003, the golden age was before HMOs became popular in the 1990s. But what's happened to average physician incomes during my career? Well, they've gone up, even after accounting for inflation. While the increases in each decade are not the same and while there are plenty of worrisome trends, there have always been worrisome trends. In this post, we'll go over the data, and you'll see what I mean.

Dr. Shippen's Records

Dr. William Shippen kept payment records from his practice beginning about the time of the American Revolution. Many patients paid in kind with goods rather than cash. He was making good money on smallpox inoculations and “male-midwifery” (aka obstetrics). But he was paid in everything from bread (a baker) to lottery tickets to a “bad painting.” He also dabbled in real estate investing. While he only made 3 pounds sterling from treating a Spanish diplomat, he made 350 pounds sterling renting him a house. He was the head of the Continental Army Medical Department. A senior surgeon at that time was paid $4 a day plus six rations. That's $4 per day x 365 days = $1,460 a year. Given that the average income back then was $65 a year, that surgeon was raking in the money. Maybe the Revolutionary War was the “golden age” for doctors.

Physician Income in the 1800s

In the early 1800s, there just weren't very many paying patients so doctors often had second jobs—such as school teacher, hotel operator, or farmer. One was even a superior court judge.

Physician Wealth in the UK

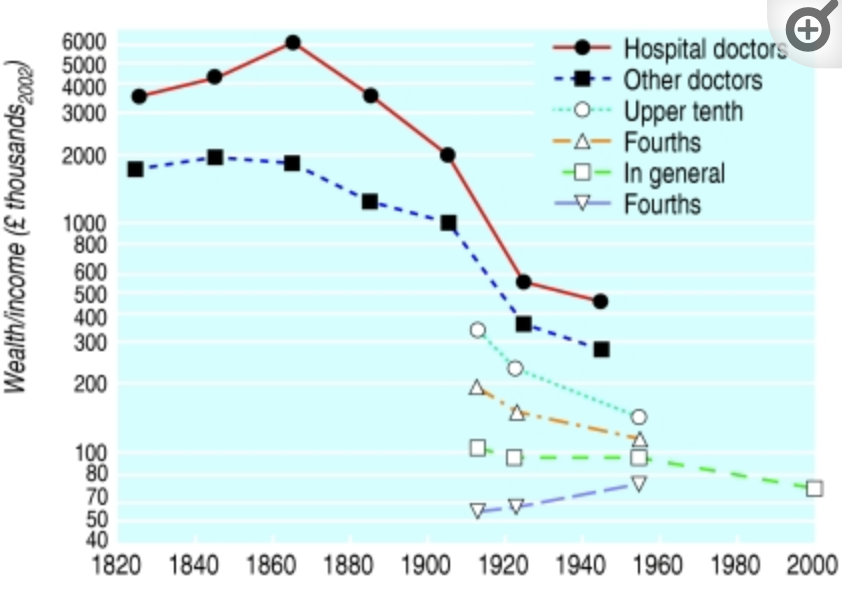

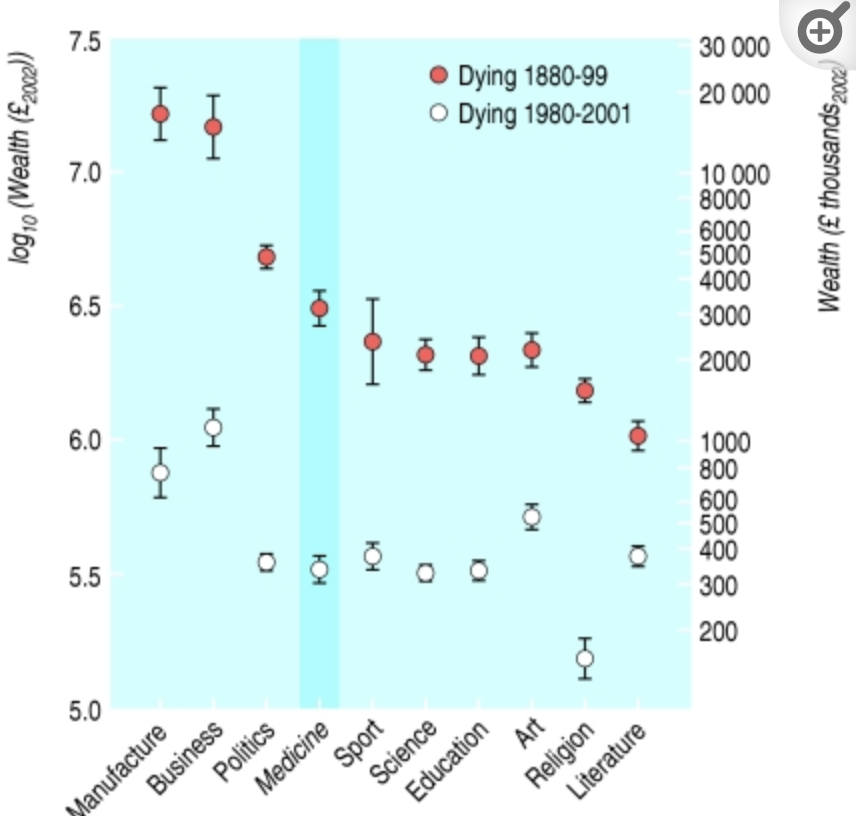

A very interesting article about the wealth (not income) of “distinguished doctors” in the UK showed a significant decline between 1860-2001.

From this, it appears the “golden age” was from 1840-1880. I'm a little skeptical, though, as the same article showed this for everyone else:

Saying people were wealthier in 1880 than in 1980 just doesn't pass the sniff test for me.

More information here:

The Most Athletic Doctor Ever and Andy Warhol’s Cookie Jar Collection

Physician Incomes Between 1914-1929

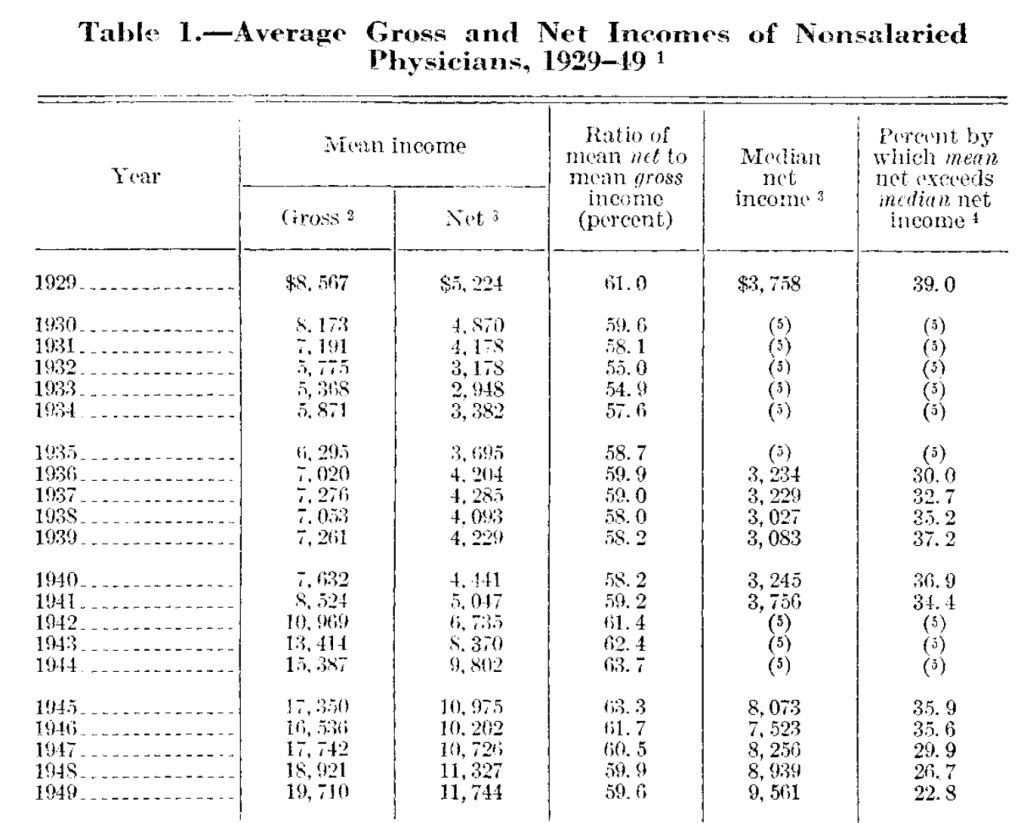

The earliest data set I could find on physician salaries begins in 1929.

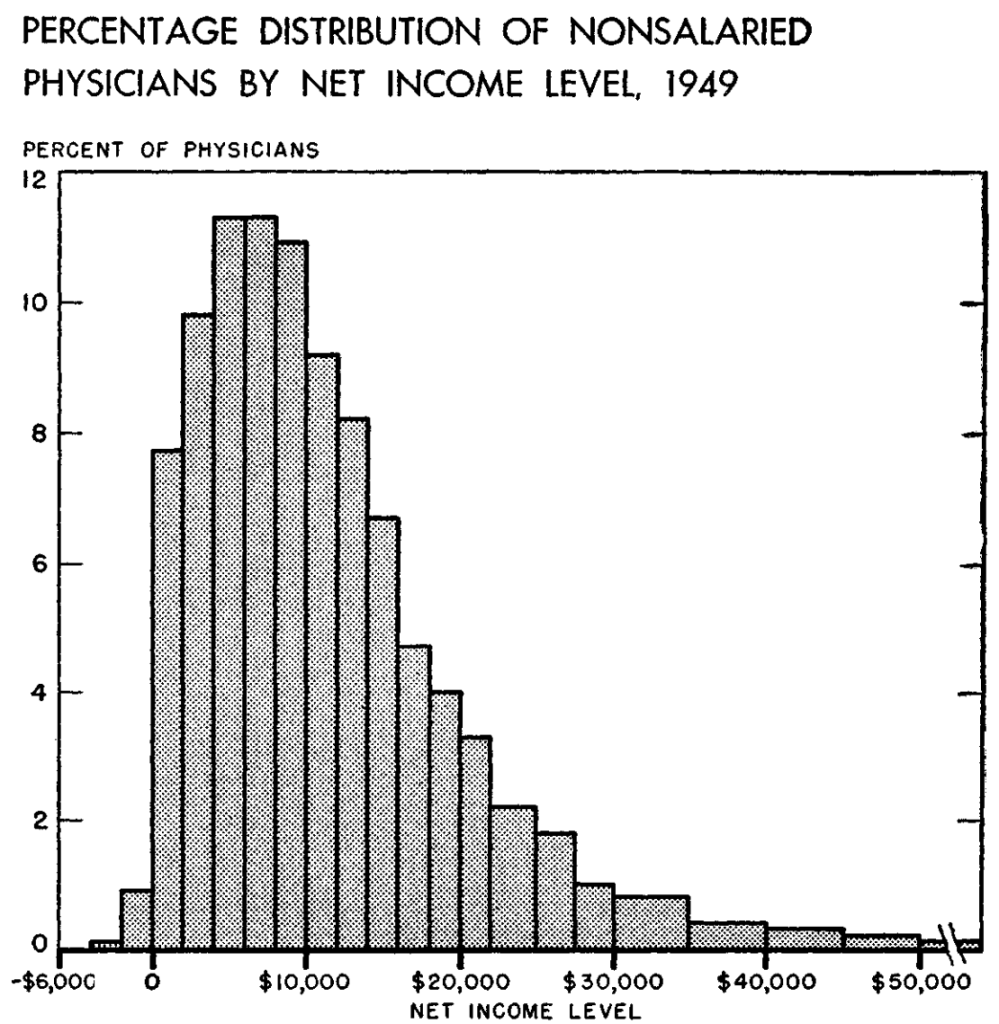

This was kind of a tough time to be a doc, though. About HALF of the country's 129,000 doctors in 1941 were recruited into the Armed Services for World War II. But here's how incomes shaped up in 1949:

I thought this was interesting because, just like now, there was a very wide range of incomes among docs 75 years ago. It's always hard to sort out all of this stuff, given the effects of inflation. So, let's compare this 1949 income of $19,710 to the senior surgeon in 1776 ($1,460) and the 2023 Medscape Salary Survey figure ($352,000).

Adjusted for inflation to 2023 dollars:

- 1776: $51,129

- 1949: $252,288

- 2023: $352,000

Hard to look at that and conclude the “golden age” was before 1949.

The Medusa and the Snail

A very interesting excerpt from this 1974 book reads as follows:

“I had forgotten what things were like in the good old days of medicine, and how different . . . I found in the other day while glancing through the yearbook of my class at Harvard Medical School at the time of graduation, in 1937 . . . Coons, as editor, decided to do something more ambitious for the yearbook than simply record the class statistics, and prepared a long questionnaire which was sent to all the alumni of the medical school from the classes which had graduated 10, 20, and 30 years earlier . . . To everyone's surprise 60% of the 265 alumni filled out the questionnaire and returned it . . . The findings of greatest interest, presented in some detail in the yearbook, concerned the net incomes of the alumni, which were, by the standards of the day, significantly higher than the AMA's figures for American physicians in general . . . We knew that interns and residents got room and board but no salary to speak of. We were glad to hear that Harvard graduates did better financially once out in practice . . .”

The median net income of the group of 165 HMS graduates, 10-30 years out of school, was between $5,000-$10,000 a year [about $80,000-$160,000 in 2024 dollars]. In the 10-year class, 43% made less than $5,000. Only five men earned over $20,000 [~$354,000 in today's money] and a single surgeon, 20 years out, made $50,000 [more than $1 million today]. Seven graduates of the class of 1927 had incomes below $2,500 [about $44,000].

The alumni were invited to send in comments along with the questionnaire, in a space marked “Remarks,” with the understanding that since so much of the form was directed at finding out how much money they were making, they might like to say something about life in general. As it turned out, most of the “Remarks” were also about money, a typical comment being the following: ‘I am satisfied with medicine as a life's work. However, I should recommend it only for the man who has plenty of money back of him. Many men never make much in medicine.' Forty-one years ago, that was the way it was [author Lewis Thomas wrote this in the 1970s].”

I loved the reference to the “good old days” in a book published in 1974 and talking about a survey done in 1937. The more things change, the more they stay the same. But residents used to live at the hospital and work for nothing but room and board. That doesn't sound like the golden age to me compared to how residents now are being paid about the average American household income.

More information here:

A Doc Created the Coolest Shoe in the Whole World

Physician Incomes in the 1950s

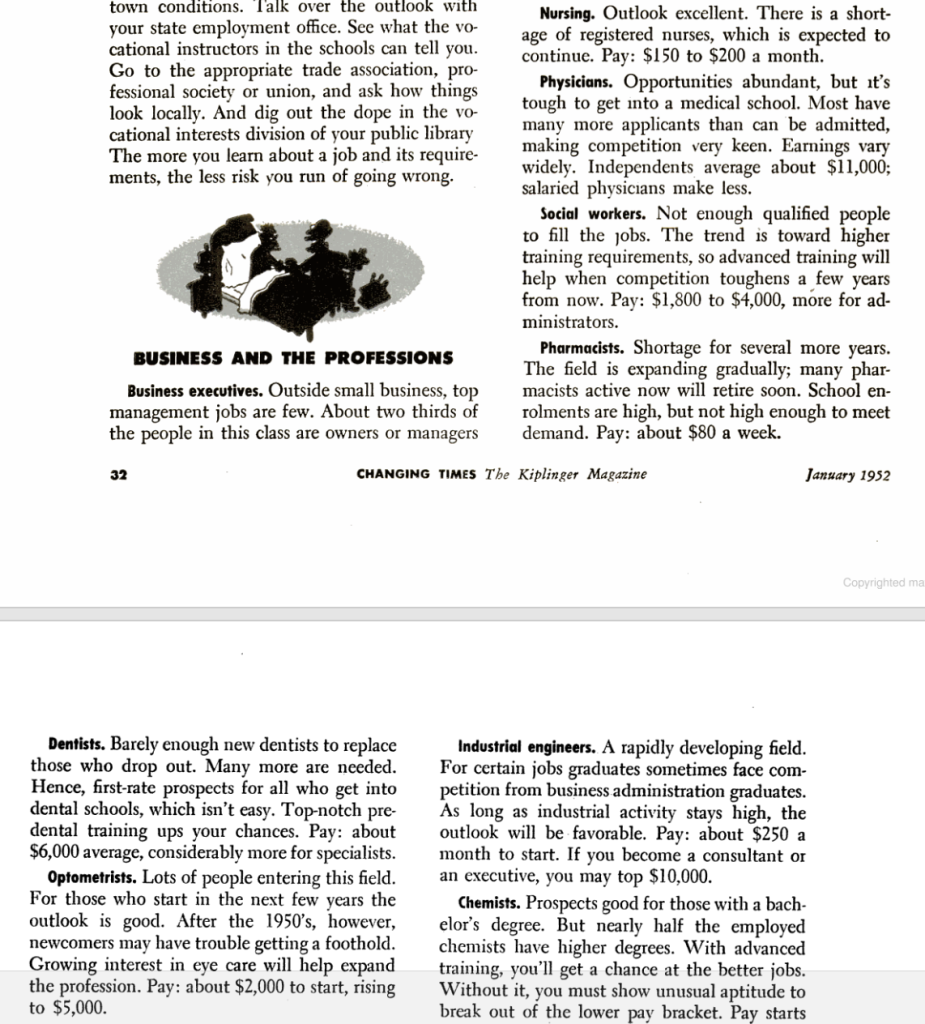

Here's a fun article from the 1950s that talks about nurses ($2,000), physicians ($11,000), dentists ($6,000), pharmacists ($4,000), and optometrists ($2,000-$5,000).

Is Physician Income Affected by Employer Health Insurance and Medicare?

In response to World War II-related inflation, the Wage Stabilization Act was passed in 1942. In response to that, employers started offering benefits, such as health insurance, instead of giving raises. These insurance companies apparently didn't negotiate much and just paid whatever doctors asked. Medicare and Medicaid went into effect in 1965, modeled on the earlier private medical insurance plans. Surgeon Richard Patterson describes the effects, promoting the oft-held view that the 1980s were the “golden age”:

“For decades, physician income had tracked cost of living increases very closely. Employer-provided insurance plans produced a significantly higher rate of growth, and Medicare blew the walls out. Private practice physicians experienced raw collection rates (without discount or fee schedule negotiation) of 98%. Doctors who were no more than ordinary in ability could, if sufficiently affable and available for their referring colleagues, realize incomes that vaulted them into the highest percentiles. Doctors suddenly had the wherewithal to invest heavily in the stock market and shopping centers, to buy airplanes and island retreats, and the health sector was mainly immune to cyclic contractions in the general economy. Just because ‘rich doctor' was a new phenomenon does not mean that it was not embraced as the just and proper standard and expectation. It became a redundancy.

Then things changed. Spiraling costs prompted controls on physician reimbursement, and doctors have experienced income reductions in real, inflation-adjusted dollars, and all that preceded the Great Recession. A colleague joined his father’s surgical practice. He was disposing of some records after his father’s death around 2000, and he came across what Blue Cross paid his father for gallbladder surgery in the 1980s. It was about 150% more that BC was paying my colleague in 2000, and that’s not even adjusting for inflation. Since inflation in the costs of running a medical practice is higher than the general inflation rate, that reduction in real income is substantial.”

But were the 1980s as good as doctors seem to think? Let's look at the data.

Physician Income in the 1970s

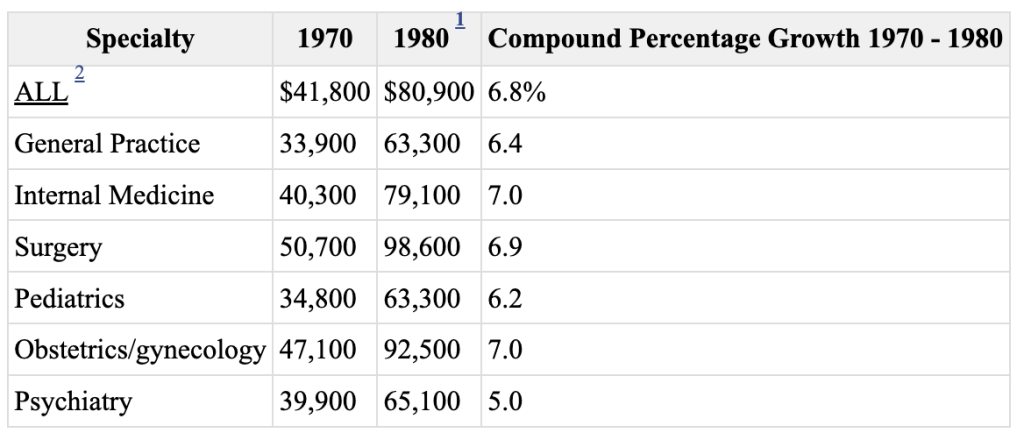

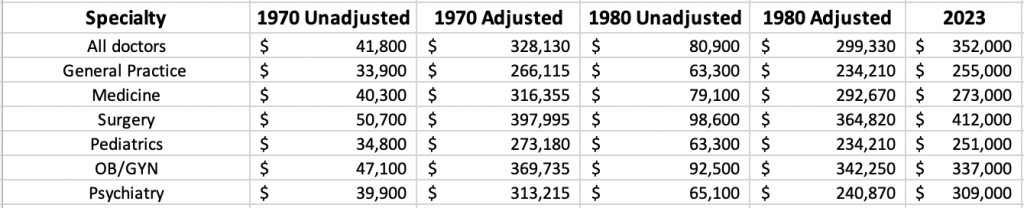

Let's start with this chart comparing 1970 to 1980.

Let's adjust each of these data points to 2023 dollars and compare them to the Medscape compensation report figures for each of those specialties and see what we get.

Now, I'm just a simple doc with some elementary spreadsheet skills, but, if anything, doctors were better off in 1970 than in 1980 and sometimes (but not usually) even better off in 1970 than in 2023 on an inflation-adjusted basis. It varies by specialty, but, in general, physician incomes ARE NOT dramatically less in 2023 than they were in 1980. That means 1980 (15 years after Medicare) was NOT some sort of golden age for physician incomes, at least on average. Physician incomes have ALWAYS been highly variable. The intraspecialty income range has always been dramatically higher than the interspecialty variation. If you're comparing an average physician's salary to a very high physician's salary from an earlier time, you're really not comparing apples to apples.

More information here:

Living Our Lives in a Dual-Physician Income Household

Here’s How Much We Make, Save, and Spend as ‘Moderate Earners’

1960 to Present

In fact, data suggests that physicians have done just fine and better than many professions over the last 60 years.

This chart is adjusted for inflation and basically says that doctors in 2015 were making 3X what doctors were making in 1960, 2X what doctors were making in 1980, and 50% more than doctors were making in 1985. I think this chart does explain the “1980s as the golden era” idea, though. Look at the slope of the line from 1980-1990 and then from 2000-2010. Real incomes weren't higher, but they were increasing faster in the 1980s.

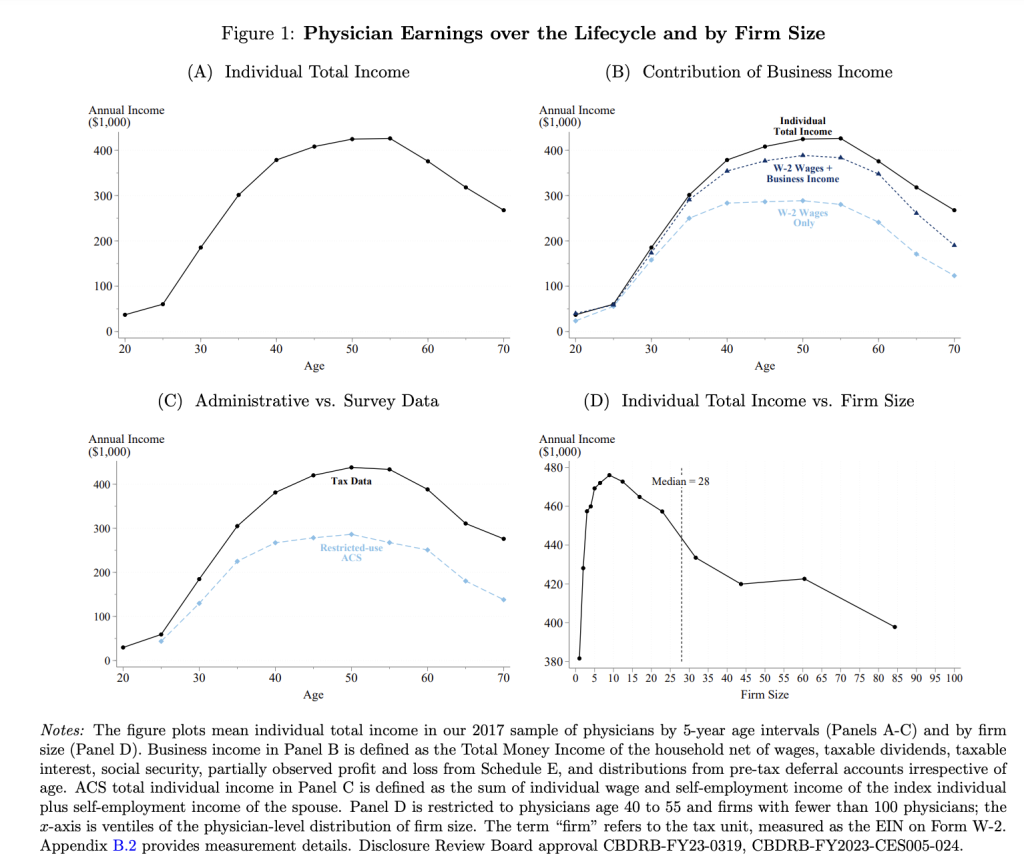

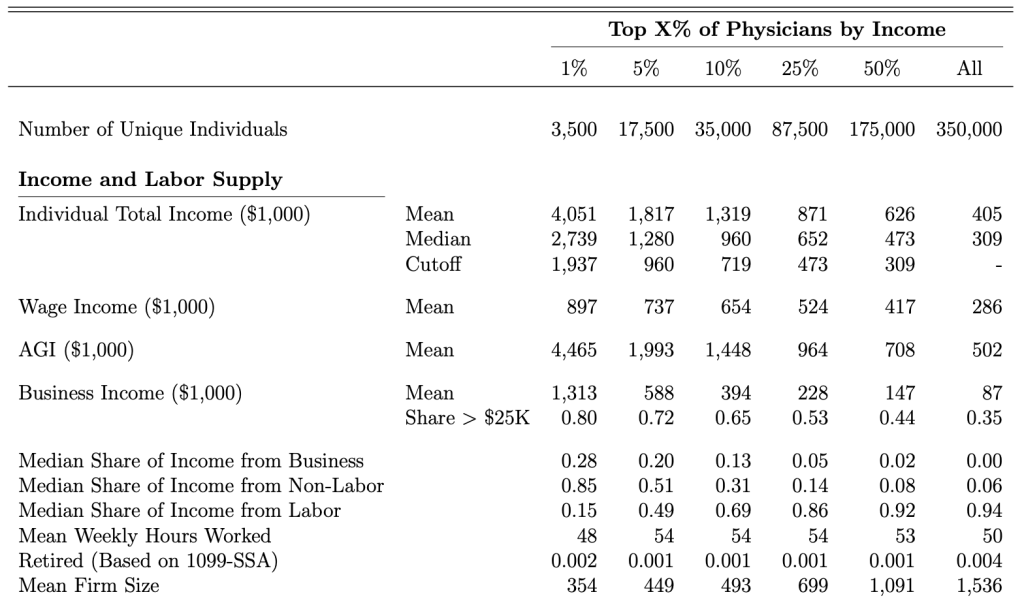

There is also a very interesting 2023 paper that looked at physician income tax returns from 2005-2017. While it doesn't do much to compare doctors to doctors in prior decades, it does suggest that doctors are doing even better these days than many people think and it contains lots of interesting figures. Let's go through a few:

In A, I was surprised to see physician earnings peak in their late 50s just like they do for most other professions. In B, I thought the comparison of wages to wages + business income to total income from the tax returns was interesting. In D, it suggests that the best-paid physicians are in groups with about a dozen docs. Apparently, medium-sized partnerships are better than solo practices and huge groups, but a huge group is still better than a solo practice.

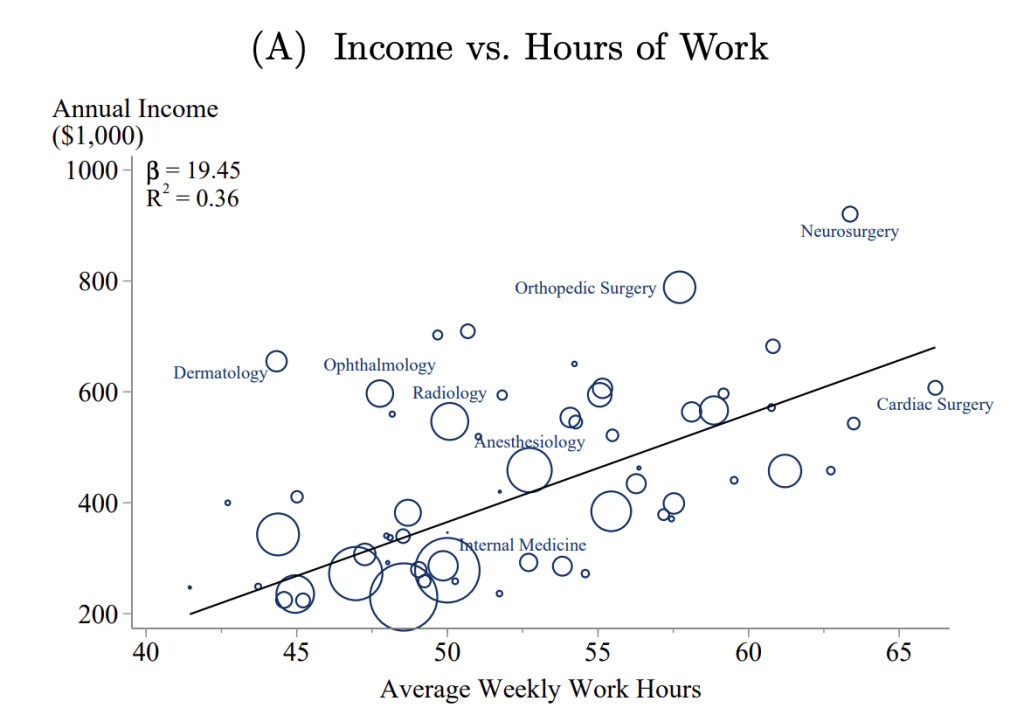

I don't think anyone is surprised to see Dermatology come out of this comparison smelling like a rose. I bet EM would have looked pretty good, too, if it had been included.

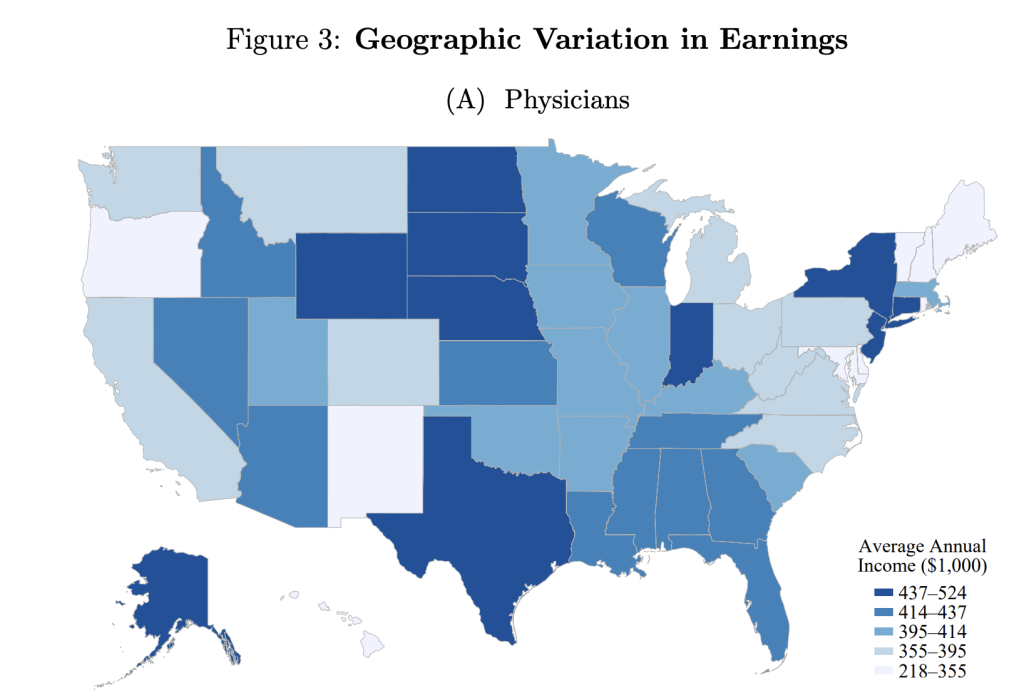

Geographic arbitrage, anyone? Maybe if you think you missed the golden age of medicine it's because you settled down in the wrong place. Portland (either one) might be prettier than Amarillo, Sioux Falls, and Indianapolis, but the golden age might just be now in the latter three places.

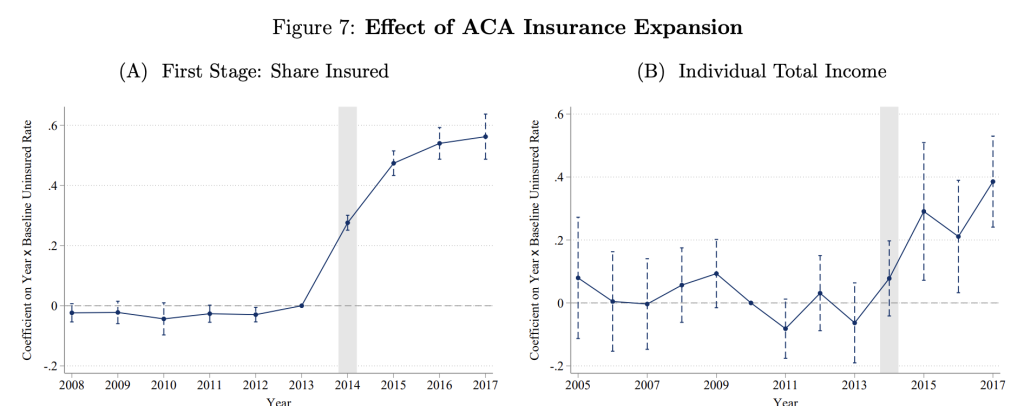

And for those of you who think Obamacare ruined your life, you might want to check the data:

Feeling competitive? Want to know if you're in the top 1%, 5%, or 10% of docs? There's a chart for that too:

The median individual physician total income is $309,000. That means $473,000 gets you into the top 25%, $719,000 gets you into the top 10%, $960,000 gets you into the top 5%, and almost $2 million gets you into the top 1%. And there are a few doctors out there absolutely killing it, such that the mean of the top 1% is $4 million. Again, if you're feeling like you missed the golden age of medicine, maybe it's just you. Maybe you need a new job. Or to start your own business. Or to move to a new state. Or to work more. Or to have spent more time training in a higher-paying specialty.

What Happened to the Big Squeeze?

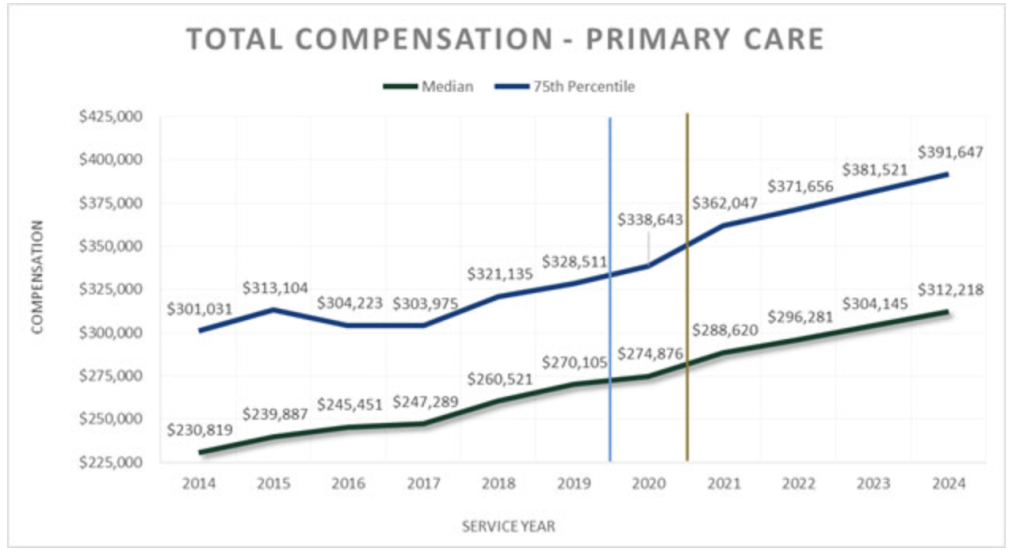

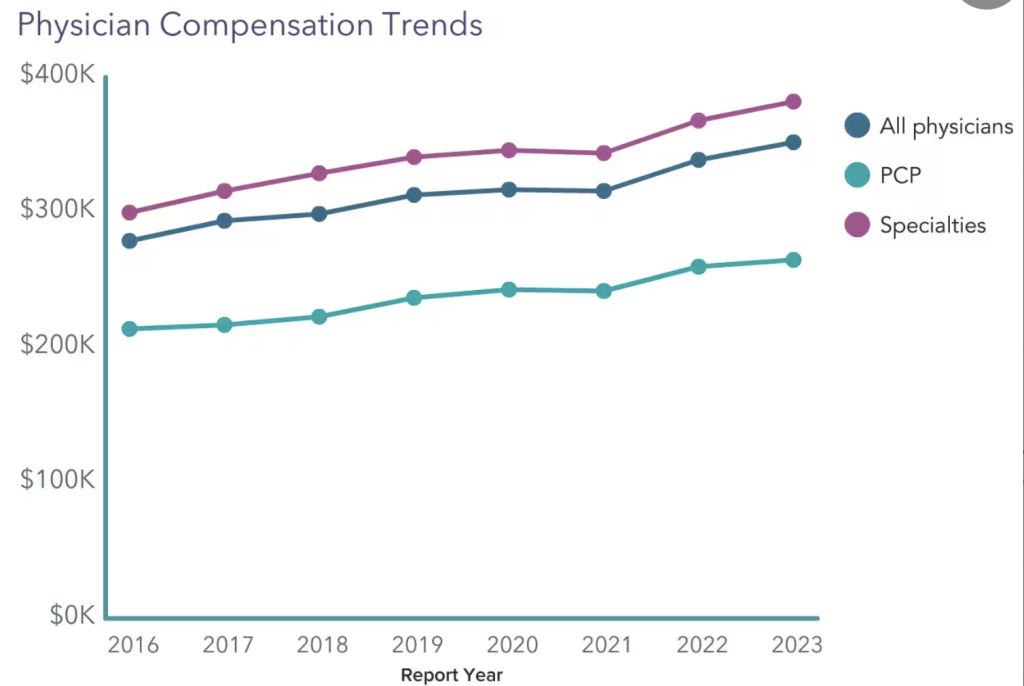

That was an interesting field trip into that paper, but let's get back to our main thesis—that there was no golden age of physician income. Lots of primary care docs, in particular, feel squeezed. I talked about the “big squeeze” in the original WCI book written in 2013 and published in 2014. I talked about how demands on physicians were increasing, salaries were not really increasing much, and (especially) that the cost of becoming a doctor was skyrocketing. The trends I feared when I wrote that in 2013 have, for the most part, failed to materialize. Take a look at primary care incomes:

The Medscape survey shows a similar trend.

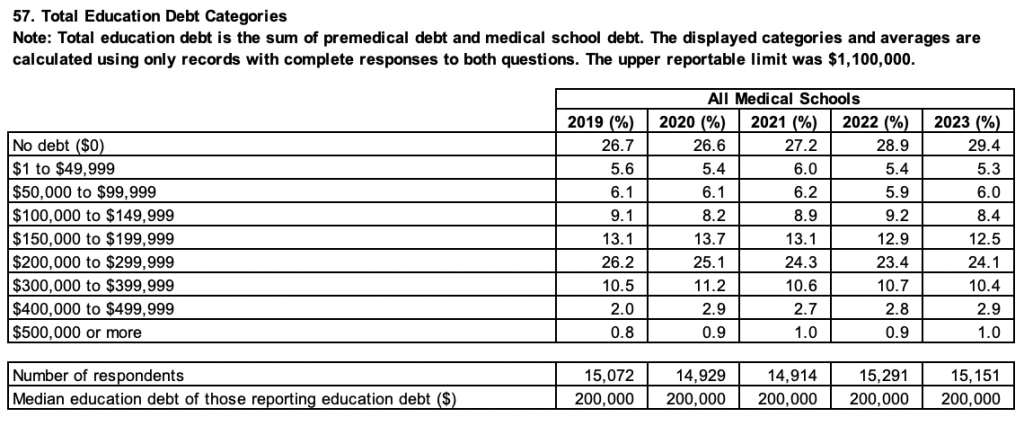

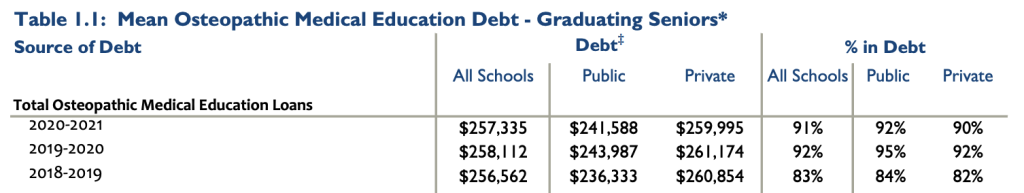

Those seem, at least, to be keeping up with inflation, no? And yes, tuition is going up, but med school indebtedness is not.

Fewer students are indebted. The average debt is not increasing. Incomes are rising. It's not much of a squeeze. It's worse for DOs, but it isn't worsening for them either.

And with PSLF becoming ever more generous, it's hard to argue for a squeeze.

More information here:

Here’s How Much We Make, Save, and Spend as ‘Moderate Earners’

The Counterargument

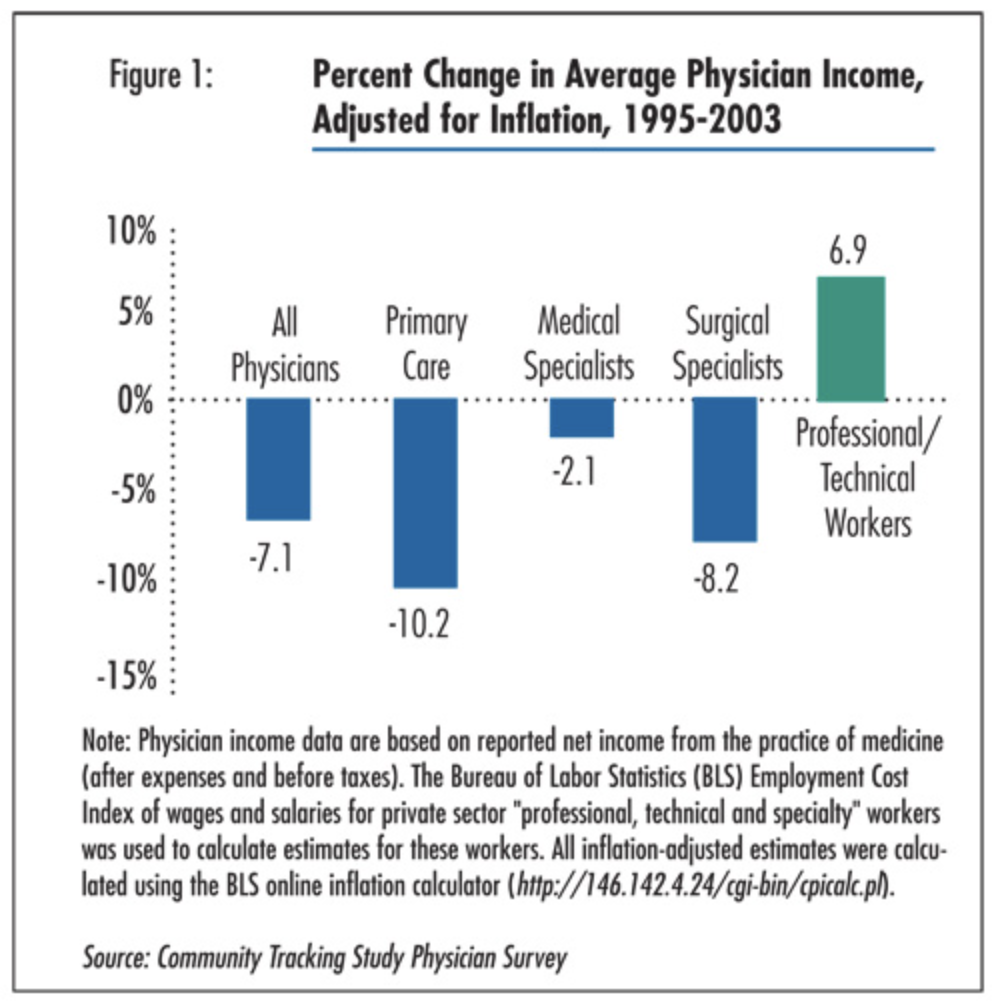

Now, I can find some data that suggests that there have been periods when physician incomes actually decreased, at least on an inflation-adjusted basis. Here's a survey from 1995-2003.

And I have seen data on Medicare reimbursements not keeping up with inflation. But I cannot find anything long-term that suggests a trend of lower physician incomes, even when adjusted for inflation.

My Worries

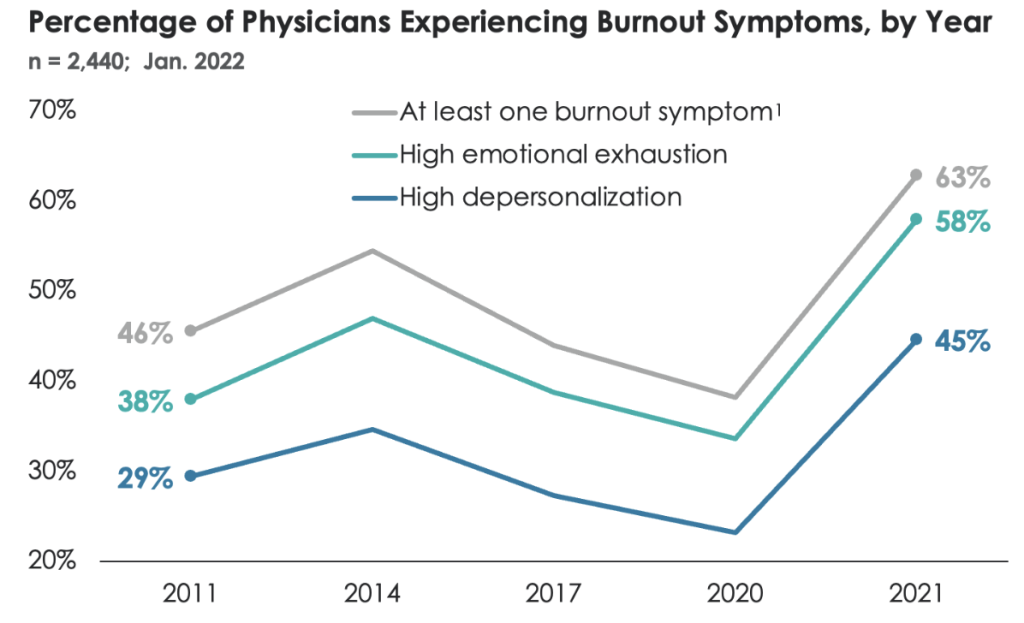

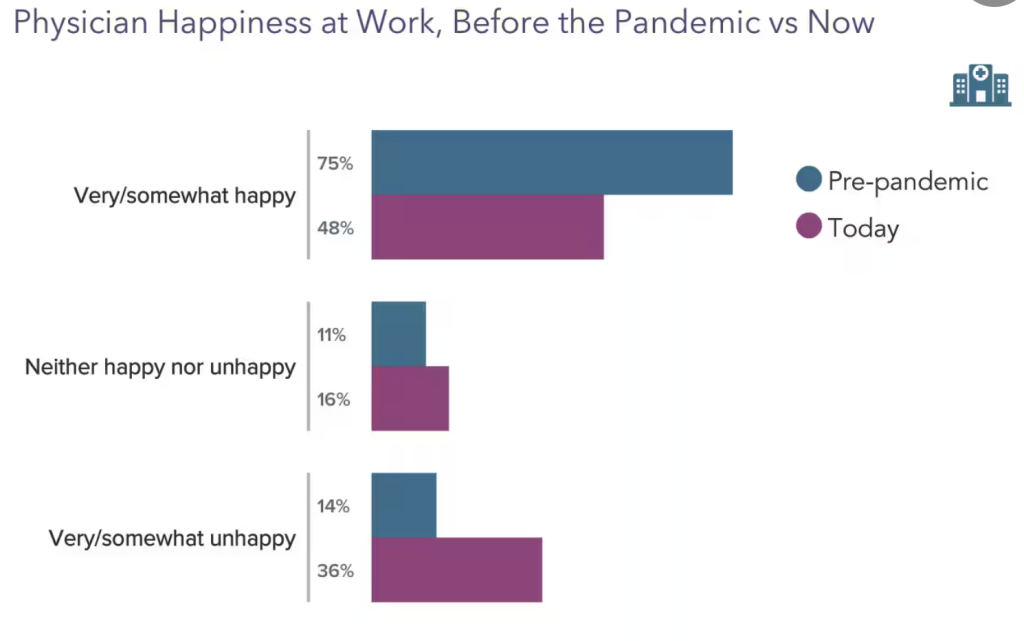

There are a couple of trends that I do worry about. The first is the increasing trend toward employment and away from ownership. From 2012-2022, the percentage of self-employed doctors dropped from 60% to 47%. As a general rule, owners earn more and are happier because they have more control over how their work is done. The second is that burnout continues to increase and happiness at work continues to decrease by just about any measurement.

Yes, I do think those two statistics are related. But I can't relate them to physician income. If there is a “golden age” for physician incomes, one can argue that it is just as much now as it was during any other time in history.

Looking to increase your income or renegotiate an existing contract? Hop on over to the WCI physician contract review page, where you can find vetted lawyers and compare your contract to other docs.

What do you think? Was there a golden age of medicine? Why or why not?