By Dr. Jim Dahle, WCI Founder

By Dr. Jim Dahle, WCI FounderIf you have been around personal finance for long, you have probably heard of “The 5-Year Rule.” However, if you're like me, you couldn't really explain the 5-Year Rule to your spouse without looking it up and spending 15 minutes understanding it again. You know why? Mostly because there are four of them. This post will be a reference post for all of us for the next time we can't quite remember what the 5-Year Rule is.

5-Year Rule #1: The 5-Year Rule for Roth Conversions

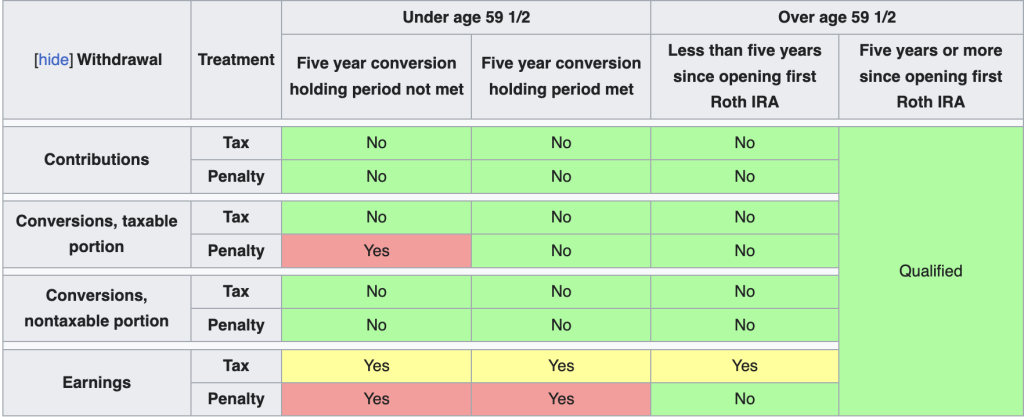

This is probably the most important rule—and the one that affects financial planning most frequently. This rule determines whether you can withdraw PRINCIPAL that came from a Roth CONVERSION PENALTY-FREE. Essentially, you must wait five tax years from the time of a Roth conversion before you can withdraw that principal free of the 10% early withdrawal penalty UNLESS you meet one of the other ways to qualify to have penalty-free withdrawals (such as being 59 ½). Thus, this rule really only applies to early retirees who want to spend Roth principal (that came from a conversion) before age 59 ½. Each Roth conversion has its own five-year clock. Note that this rule does not apply to non-taxable conversions (Backdoor Roth IRAs, Mega Backdoor Roth IRAs).

Chances are good you're not going to get caught up in this rule. That's because Roth IRA withdrawals come out in the following order:

- Contributions

- Conversions

- Earnings

If you don't churn through your contributions in the first five years, you're fine. Plus, when you do withdraw converted principal, you start with the first conversion you ever did and work your way forward. That means if you've done four Roth conversions over the years and three of them have already met their 5-Year Rules, you can probably live off the first three until that final one has met its own 5-Year Rule. Note that violating this rule does not result in you having to pay income taxes on the withdrawal since you are withdrawing principal that has already been taxed. It just means you have to pay a 10% early withdrawal penalty on the withdrawal.

Why Does This Rule Exist?

This rule exists to prevent you from withdrawing money from your traditional IRA before age 59 ½ without paying the 10% penalty simply by first converting it to a Roth IRA before withdrawing it. Essentially, the rule says you can still do this; you just have to wait five years after the conversion. FIRE folk who want to retire at 42 and live on Roth IRA principal might want to make sure they have that conversion done by age 37. Note that earnings on the Roth IRA still can't come out penalty-free until the Age 59 ½ rule (or another exception including death, disability, first home, or the Substantially Equal Periodic Payments rule) is met.

The Backdoor Roth IRA Exception

Note, however, that there is an exception if the conversion is of post-tax dollars. As explained in a nice chart in the Bogleheads Wiki on Roth IRAs:

The conversion of the non-taxable portion of a contribution does NOT have an associated penalty.

More information here:

59 ½ Rule — How to Get to Your Money Before ‘Retirement Age’

5-Year Rule #2: The 5-Year Rule for Roth Contributions

This 5-Year Rule is used to determine whether the withdrawal of EARNINGS that came from a Roth IRA CONTRIBUTION will be TAX-FREE. Remember that contributions always come out tax-free. Earnings generally do, too, but only if all of the requirements are met, one of which is this 5-Year Rule. This rule is in addition to the other rules (such as being at least 59 ½ or having a valid exception to that rule) that allow for tax-free withdrawals of earnings.

The rule is that five tax years must have passed from the time of the first contribution to any Roth IRA before withdrawals of earnings from all Roth IRAs are tax-free. Technically, the five-year period could be as short as three years and eight months since you could put in a contribution for a given tax year on April 15 of the next year. For example, let's say you make a 2020 contribution on April 15, 2021. 2020 counts. So does 2021. Then, 2022, 2023, and 2024 pass. On January 1, 2025, you can withdraw the money tax-free (assuming you meet the other requirements). But you cannot make a tax-free withdrawal of earnings before that.

Note that the clock starts after the first time you make any contribution to any Roth IRA. All four of my children have already met the 5-Year Rule since they made their first IRA contribution years ago. But if, for some bizarre reason, you never contributed to a Roth IRA until you were 57, you couldn't make tax-free withdrawals of earnings at age 59 ½. You'd have to wait until age 62.

You can also start this five-year clock by converting money from a traditional IRA (or 401(k)) into a Roth IRA or by rolling money from a Roth 401(k) into a Roth IRA). Note that there is only one Roth IRA contribution clock, no matter how many contributions or Roth IRAs you have. If one Roth IRA has met this requirement, they all have.

While death is an exception to the early withdrawal penalty, it is not an exception to the 5-Year (contribution) Rule. If someone opened a Roth IRA and then died the next year and the heir took out earnings prior to five years passing, they would have to pay income taxes on those earnings. That's unlikely because the principal comes out first and they could stretch out that Roth IRA for up to 10 years, but it could happen if they wanted all that money right away.

Complicated enough for you? Just wait. This rule also applies to Roth 401(k) contributions. But instead of there only being one clock, each Roth 401(k) has its own clock. And all of those clocks are separate from the Roth IRA clock. If you combine two Roth 401(k)s, you do get to use the one with the longer clock, but if you roll a Roth 401(k) that has met its 5-Year Rule into a Roth IRA, the Roth IRA does not get to use the Roth 401(k) clock. Crazy right? But them's the rules.

The bottom line for this rule is that it really should not catch very many people. Very few people who have a Roth IRA will not have it for at least five years before they start withdrawing from it. And even if they do need to withdraw from it, they can just take out the principal and wait on the earnings. But if you're in some kind of unique situation where this rule could apply, you should be aware of it.

Why Does This Rule Exist?

This rule is simply to encourage people to use Roth IRAs for long-term saving/investing for retirement. Without it, people could contribute to a Roth IRA at age 58 and pull it out at age 60 with two years of tax-free growth without really making a long-term investment toward their retirement. Or perhaps they could use it to save up for six months to make a house down payment (one of the exceptions to the Age 59 ½ rule). The government wants you to use this tax-free account for retirement.

5-Year Rule #3: The 5-Year Rule of Inherited IRAs

The third 5-Year Rule out there has to do with inherited IRAs. There are a lot of options when it comes to taking money out of an inherited IRA. They have also been changing recently, so the rules have been seemingly different every year for the last few years. Whether and how one who has inherited an IRA has to take Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) from it depends on when the owner died and what their relationship was. Generally speaking, one must have distributed the entire IRA by the end of the 10th year after the year in which the IRA owner died. This is “The 10-Year Rule.” One can still stretch the IRA tax protection for 10 years but not for a lifetime like one could before 2020. I've called this the New Stretch IRA. By the way, the IRS has now clarified that one must take RMDs from an inherited traditional IRA (Roth IRAs are an exception) each year of those 10 years, but only if the decent was already taking RMDs. In that case, you cannot just wait until the 10th year and take it all out like people initially believed. However, if the decedent was not taking RMDs yet, you can wait until the end of the tenth year and take it all out then if you want.

There are exceptions to the 10-Year Rule for certain Eligible Defined Beneficiaries (EDBs) including someone who is:

- The IRA owner's spouse

- The IRA owner's child until they reach 18

- An individual not more than 10 years younger than the IRA owner

- Disabled

- Chronically ill

If the heir is an EDB, they basically have the old stretch IRA, where you can stretch that IRA over your entire lifespan. Once a child has hit 18, the 10-Year Rule starts, and then they have the New Stretch IRA. Spouses also have the option to move the money into their own IRA.

So, where does the 5-Year Rule come in? Before 2020, a person who inherited an IRA had two options to avoid taking money out of the inherited IRA right away. They could take the money out via RMDs based on their own lifetime expectancy, or they could avoid taking out any RMDs, so long as they took all the money out within five years. That rule still applies to an inherited IRA if the owner died before 2020.

However, if an owner dies after 2020, there is also a 5-Year Rule IF the beneficiary is not a person. For example, if the IRA owner designates a business, a trust, a charity, or just their estate (which is what happens if no beneficiary is named), there are no RMDs. But all the money must be distributed by the end of the fifth year following the death of the IRA owner. It can be distributed more quickly but not any more slowly. There is a little exception for trusts that the IRA describes this way in Pub 590-B.

“A trust can't be a designated beneficiary even if it is a named beneficiary. However, the beneficiaries of a trust will be treated as having been designated beneficiaries for purposes of determining Required Minimum Distributions after the owner’s death.”

I think the IRS is saying that an IRA naming a trust as a beneficiary can be stretched over a lifetime (rather than five years) as long as the trust beneficiaries are EDBs and over 10 years if the beneficiaries are individuals who are not EDBs. Otherwise, it's five years.

Why Does This Rule Exist?

Prior to 2020, the 5-Year Rule was just an option you could take if you wanted. People probably mostly took it when they forgot to take out RMDs and didn't want to pay that big fat 50% excise tax on missed RMDs. It allowed them to avoid hassling with RMDs, too. You could just take it all out in year 4 or 5 and never bother with figuring out RMDs. Since 2020, it basically discourages people from leaving IRAs to anyone but real people. It seems to me that Congress wants you to leave your IRA to your spouse, kid, brother, friend, or somebody disabled or ill instead of your family-limited partnership. This is one way they encourage you to do so.

More information here:

5-Year Rule #4: The Social Security 5-Year Rule

There is one more 5-Year Rule to be aware of. To collect Social Security disability, one of the requirements is to have worked and paid into the system during five of the last 10 years. Social Security is not just about old-age payments. There are also disability payments and survivor benefits. The 5-Year Rule only applies to disability. Unlike many pensions that base the benefit amount on the last 3-5 years of working, Social Security old-age benefits are based on your 35 years of highest pay. The 5-Year Rule has nothing to do with this benefit.

Why Does This Rule Exist?

Simply put, taxpayers don't want to pay you disability benefits if you haven't worked for decades. They reason, “Why would you deserve disability payments when you're not working anyway?” and “Why should we pay you a benefit if you haven't been paying into the system regularly?”

Four separate 5-Year Rules with varying levels of complexity and contradictory rules. No wonder we can't keep them all straight.

What do you think? How do you keep all of these 5-Year Rules straight? Has any of them ever affected you?