The Paris Olympic Games begin this week, where the whole world comes together for 16 days to care passionately about the 3,000-meter steeplechase, Greco-Roman wrestling, artistic/synchronized swimming, and trampoline gymnastics before we all forget these events even exist until four years from now.

It should come as no surprise that some Olympic athletes went on to become doctors—reportedly more than 100 of them in the US alone. So, in the spirit of the Olympic games and all the peace and love they bring to the world (actually, that was Woodstock, but you know what I mean), let’s celebrate those athletes who sacrificed their physical well-being for their country before giving their mental acuity and life-saving abilities to the world.

Here are a few of my favorite examples of US Olympians who became doctors.

Olympians Who Became Doctors

Tenley Albright

Figure skating has been one of the most popular Winter Olympic sports for decades. Olympic medalists introduce themselves to US audiences and bathe in the adulation of their country because of their superhuman ability to land double Axels and triple Lutzes. Think of Dorothy Hamill, Peggy Fleming, Kristi Yamaguchi, and Tara Lapinski (and 1988 bronze medalist Debi Thomas, who later became an orthopedic surgeon).

But before all of them, there was Tenley Albright, a polio survivor and the first US woman to win a gold medal in figure skating in 1956 who became beloved in the aftermath. She eschewed the chance to be a professional figure skater and attended Harvard Medical School instead, where she was one of just five women to graduate from her class. Interestingly, she never actually graduated from college before her acceptance into medical school (she had to interview seven times before Harvard deemed her medical school-worthy despite her lack of a college diploma).

Perhaps she was partially inspired by her father. After winning an Olympic silver medal in 1952, she was set to compete in 1956, but she badly cut her ankle only a few weeks before the competition, putting her meet in jeopardy. Her father, however, was a surgeon, and he treated her wound. She later became a surgeon herself.

“At that time little girls weren’t expected to have career plans,” the 89-year-old Albright said, via the United States Olympic and Paralympic Museum. “But I remember thinking I would be a doctor from the time I was playing with my dolls. By the time I was 8, certainly, I was fascinated about what made people tick.”

More information here:

Pickleball’s Newest Sensation Is a First-Year Medical Student Who Just Came Out of Nowhere

Ron Karnaugh

As swimmer Ron Karnaugh prepared himself to participate in the 200 individual medley swimming event in the 1992 Summer Olympics in Barcelona, his proud father, Peter, met his son’s eye and waved to him at the Opening Ceremonies. Moments later, Peter suffered a fatal heart attack, changing Ron’s life forever.

“It's something I'll never forget,” Karnaugh told the AMA Journal of Ethics in 2000. “Not a day goes by that I don't think about it. For a year or two, it was really hard to cope with, thinking why me and why did this happen at the Olympics, which was supposed to be the best week of my life. But having gone through medical school, I see how people live and die every day, and I feel really grateful for the time that I had with him.”

Ultimately, Karnaugh decided to swim his races, and he ended up finishing sixth in the 200 IM final.

After experiencing the unexpected death of his 61-year-old father and watching his mom fight throat cancer, Karnaugh decided to swim the open lane to medicine. He graduated from New Jersey Medical School in 1997 but deferred his post-graduate training to rededicate himself to swimming even though he was already in his early 30s. Karnaugh, who broke the American record in the 200 IM in 1993, finished third in the 200 IM at the 1998 World Championships, but he failed to make the 2000 Olympic team.

Looking back, the PM&R physician who specializes in interventional pain medicine drew inspiration from those who tried to help his father.

“Seeing how meaningful it was for the physician to help my own parents,” Karnaugh said, via Hackensack Meridian Health, “that was the catalyst for my own interest in medicine.”

Benjamin Spock

Benjamin Spock was one of the most famous doctors in America, thanks to his mega-selling The Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care (the only book to outsell Spock’s 1946 work that moved more than 50 million copies in the 20th century was the Bible). His ideas on parenthood were revolutionary at the time (he was big on the idea of parents being more nurturing to their children while also telling parents that they should be more self-confident in their own abilities), and he rode that wave to a life of fame.

And he was also pretty awesome at rowing, winning a gold medal along with seven teammates from Yale in the 1924 Paris Olympics. How dominant was Spock’s crew? They beat the second-place Canadians by more than 15 seconds (or nearly four boat lengths).

As Spock later said, “You’re not meant to win a race that short by as much as a boat length.”

Some of Spock’s parenting ideas were or have since become controversial—he recommended a vegan diet for children over the age of 2, and in early editions of his book, he used only “he” pronouns when mentioning a baby and mostly ignored the impact of fathers—and he later transformed into a radical political figure. But no other person impacted Baby Boomers and how they then raised their own children more than Dr. Spock the Olympic champion.

Abby Johnston

Abby Johnston was already a 2012 Olympic silver medalist in diving when she bumped into Gevvie Stone at a McDonald’s in the Athlete’s Village in London. The two met while standing in line, and after some get-to-know-you conversation, Stone revealed to Johnston that she had managed to train for her Olympic performance in rowing even while attending medical school.

That struck a chord with Johnston.

“Starting medical school didn't necessarily mean an end to the athletic career,” Stone told ESPN.

With that in mind, Johnston got into Duke medical school after placing second in the 3-meter synchronized diving event in London, and despite all the hours she spent learning to become a doctor, Johnston managed to snag a spot on the 2016 Olympic team as well.

She asked Duke to basically swap her second and third years of medical schooling (she would do research, which is normally what happens in the third year, in her second year, and then put off clinical rotations, which is what normally happens in the second year, until after the Rio Olympics in her third year). Duke gave her the thumbs up.

“I think I do better when I have multiple things going on so I'm not just focused on diving—because I can be really hard on myself,” she said in 2015.

The seven-time national titlist finished 12th at the Olympics in 2016. Two days later, the now-ER doc began her psychiatry rotation.

“I think athletics has a lot of parallels to medicine,” she told OnlineMedEd. “There’s a lot of teamwork, of course, especially in the emergency department. You’re working with techs, nurses, and [the] pharmacy to try and address the problem.

“I also think being in the emergency room is a bit of an adrenaline rush, just like competitions. You don’t know what is coming through the door, and you have to make a game plan before the person gets there. What supplies do we need? What support do we need? What other residents or trauma team members need to be present? I think that, for me, it gives me that adrenaline rush that I once thrived off in athletics.”

Eric Heiden

Though this post wasn't meant to be a roundup of every Olympian who became a doctor, we've received a number of emails and comments about Eric Heiden, one of the greatest US speedskaters in history who went on to become an orthopedic surgeon. So, yeah, maybe not including him in the original post was an oversight on my part. Let's correct that now.

Heiden won five gold medals at the Lake Placid Winter Olympics in 1980 (from the distance events to the sprints), the first time anybody had ever done that, while also setting four Olympic records and a world record. After he retired from speedskating, he became a world-class cyclist and competed in the 1986 Tour de France. Later, he graduated from Stanford's medical school and became an orthopedic surgeon specializing in sports medicine.

Along with Roger Bannister, Heiden is one of the great athletes ever to wear a stethoscope and a white coat.

And he's certainly got his fans in the WCI community. As one commenter wrote below who went to medical school with him: “He was a very approachable classmate and had the most impressive gastrocnemius muscles I have [ever] seen.”

Money Song of the Week

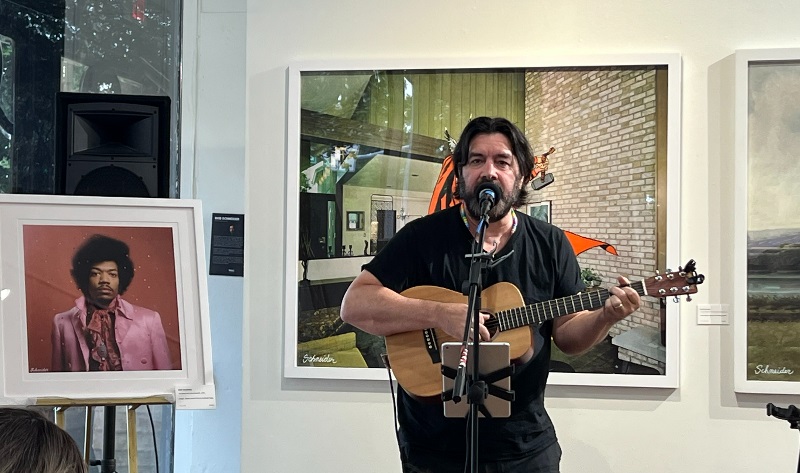

My wife and I went to an art gallery a couple of weeks ago with some friends, and the highlight of the showing was a sitdown interview with Bob Schneider, an Austin, Texas singer-songwriter fixture who’s been writing and releasing clever tunes for decades.

I didn’t know much about Schneider, but he played a few songs after the gallery curator and he talked about his visual art. And I think I began to understand. From the three songs he played in front of a couple dozen people at the art gallery, I could hear a little Tom Waits and a little Lin Manuel-Miranda and a little G. Love and Special Sauce.

He had some interesting visual art (the one I liked best you can see below, placed to Schneider’s right—it’s an AI-generated portrait of Jimi Hendrix that also looks a little like Andre 3000 with confetti scattered across the canvas). The piece is interesting and a little strange, but most of all, it’s fun. Which was also the tone of Schneider’s mini-concert. Interesting and fun and a little off-kilter.

Bob Schneider next to his AI-generated Jimi Hendrix portrait. If you zoom in, you can see the confetti on the portrait

Schneider, the former frontman for The Ugly Americans and The Scabs, has written more than 1,000 songs, and I didn’t really have time to go through his extensive catalog to find a true money song. But let’s go with I’m Good Now, a tune that was released in 2004 and tells the tale of a man on the run who moves to Mexico and meets a doctor who ends up tragically dying—and what they both learn in the process.

At least, that’s my guess. I really have no idea if that’s what this song is supposed to mean. As Schneider sings,

“As she ran home he lay on the floor dying/Wondering about the things he'd done/Thinking about his life and the fun he'd had/Choices that he made and roads he had taken/And he thought about his kids and all the crazy things he did/And he wondered if anything at all really matters.”

I suppose there’s a lesson in there. Live in the present, enjoy what you have when you have it, leave the world a little better than how you left it, maybe sprinkle a little confetti behind. Because in the end, we’re all headed to the same place anyway. Hopefully when it’s all over, we’ll all be good too.

More information here:

Every Money Song of the Week Ever Published

Tweet of the Week

If you can master this skill, it’ll help you win the game.

“Lack of FOMO” has to be one of the most important investing skills.

— Morgan Housel (@morganhousel) May 13, 2022

What other high-level athletes do you know of who eventually became doctors? Can you imagine the kind of dedication they must have to pull off those kinds of accomplishments?