When you’re young and investing for a far-off retirement date, the only risk you’re really concerned with is volatility—or how much your portfolio swings in value in response to good and bad economic news. Risk management, in this case, is mainly accomplished through building a properly diversified portfolio with an asset allocation to stocks and bonds in a proportion that allows you to meet your return goal while not exposing you to volatility you cannot handle.

The problem is that most advisors and individuals continue to view the asset allocation decision as the primary tool to manage the new risks that emerge as one nears and enters retirement. Of primary concern among these new risks is the Sequence of Returns Risk (SORR). The greater your portfolio’s volatility, the more exposed you are to the negative exponential effects a bad sequence of returns can have on your portfolio’s longevity, placing you at a greater risk of exhausting your resources prematurely.

The good news is there are other tools and strategies better geared toward managing SORR. As a bonus, many of these tools and strategies allow you to maintain a higher allocation to stocks (and, thus, return potential) than would otherwise be the case as you enter and enjoy your retirement.

The Definition of Risk

Most know if you invest all your money in a single stock, you risk the loss of your investment. In 1941, General Motors made 44% of all the cars in the US, and it had become one of the world’s largest corporations. In June 2009, General Motors filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, wiping out shareholder stock value. If you had all of your portfolio invested in GM, you’d be in trouble. A portfolio of individual stocks exposes you to unsystemic (or company-specific) risk. This kind of risk exposes you to permanent loss. This is why diversification of your investments has long been stressed as best practice.

Fortunately, investors today have access to a wide variety of low-cost, tax-efficient, well-constructed index fund ETFs. With only a couple of index fund holdings, investors can build portfolios that give them exposure to thousands of different companies across the globe. When you have a properly diversified portfolio, risk is no longer defined by permanent loss but rather by volatility (i.e. standard deviation). When times get tough, your portfolio’s value will fall as economic conditions threaten the performance of all companies. Still, if you can hold steady, values will return when the economic threat dissipates. Even if a few companies went bankrupt, your portfolio wouldn’t really feel it since their individual effect on your portfolio gets diluted or diversified away.

More information here:

An Appropriate Amount of Investing Risk

25 Things You Must Do Before You Retire (and Here’s a Checklist to Help)

Your Asset Allocation Controls Your Volatility

Once you have built a diversified portfolio, your asset allocation decision between stocks and bonds controls your level of volatility. Stocks have higher return potential than bonds, but they also add more risk in terms of their possible variation in value. In other words, the greater the proportion of your portfolio allocated to stocks, the greater the potential variation in value swings you can expect.

The risk of being too exposed to bonds (or conservativeness) is that your long-term returns will suffer (especially after inflation). The risk of being too exposed to stock (or aggressiveness) is that you risk selling at the bottom of a market downturn because you cannot “stomach” the decline and then you most likely miss the recovery, making what was a paper loss an actual loss.

Introduction to Sequence of Returns Risk

Most WCI readers will be familiar with the concepts of diversification and the asset allocation decision. Less familiar to many is the concept of SORR and the danger it poses as you near and start retirement.

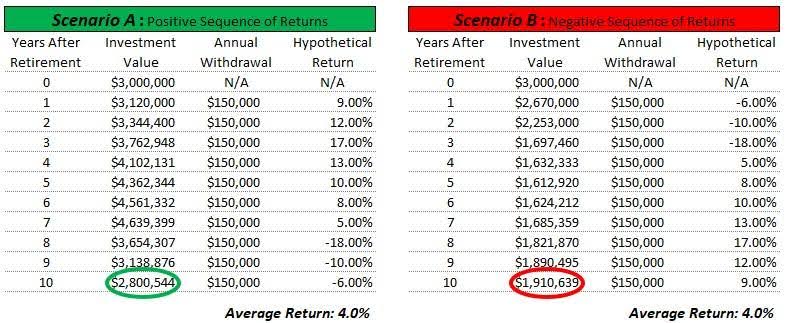

When amounts of money are coming into or out of a portfolio, the average return on a portfolio matters much less so than the actual sequence of returns you experience. For example, suppose you had two retirees (A and B) start with $3 million portfolios, and each take $150,000 in annual withdrawals:

You can see that both retirees earned the same average return of 4% on their portfolios over the 10 years, but retiree B is left with ~$890,000 (or 32%) less.

The retiree in Scenario B was irreparably harmed by continuing to withdraw $150,000 per year from assets that were down in value earlier in retirement. Not only did it take more assets to generate the $150,000 per year because of depressed market prices, but those assets were also gone from the portfolio and unable to participate in the ensuing impressive market rebound in years 4 through 10. The timing of outflows under Scenario B in the presence of a negative sequence of returns had a material adverse impact on the retiree.

More information here:

4 Methods of Reducing Sequence of Returns Risk

The “Retirement Red Zone”

Prudential Insurance coined the term “Retirement Red Zone” to represent the five years before and after retirement where an individual is most exposed to Sequence of Returns Risk. In the prior example, Retiree B showed what could happen if you experience a negative sequence of returns just after retiring.

But what about the risk leading up to retirement?

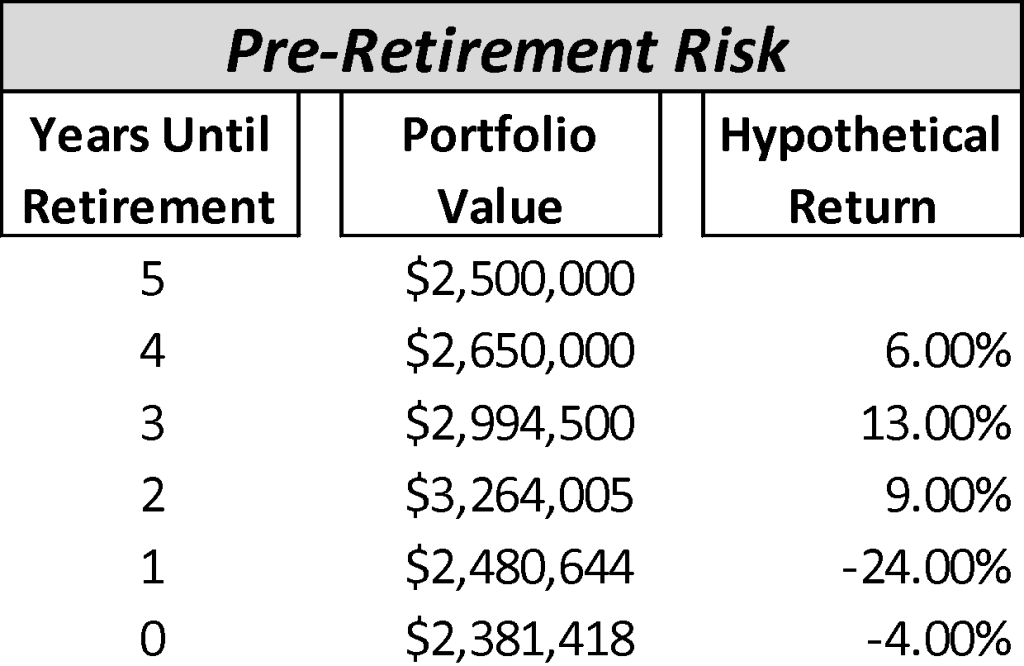

Your portfolio’s value in the five years leading up to retirement will be determined mostly by your sequence of returns, as the relative impact of contributions is dwarfed by the effect of compounding returns. For example, say a couple is five years from planned retirement with an investment portfolio of $2.5 million. Working with their retirement specialist, they determined that $3 million would be the proper portfolio target to support their desired retirement lifestyle. In this case, assuming no contributions to simplify the example, this couple would only need to earn a 3.71% average annual rate of return to close the gap and meet their goal. Closing this gap sounds easy, given the historical average annual return from a 60% stock/40% bond portfolio. Vanguard’s LifeStrategy Moderate Growth Fund (VSMGX), which tracks a diversified 60% stock and 40% bond portfolio, has returned an average of 7.35% over the last 30 years (since 1994).

Here is where SORR comes into play. What if, two years before retirement, this couple experiences the following negative sequence of returns?

Experiencing this negative sequence of returns so close to the couple’s planned retirement date turned what once looked like an easy glide path into retirement into a shortfall of over $600,000 by their planned retirement date.

More information here:

The 4% Rule and Safe Withdrawal Rates

The Silliness of the Safe Withdrawal Rate Movement

Asset Allocation Is the Wrong Tool for the Job

For decades, industry professionals have known about SORR. It is the Sequence of Returns Risk that causes the wide variation of outcomes in Monte Carlo simulation analyses. It is also why you’ve probably heard of the ridiculous rule of thumb: “Hold no more than 100 less your age in stock.” The financial advisory industry’s narrow focus on money management (and collecting fees on the size of a portfolio) has led to the asset allocation decision being the only tool in their toolbox.

Trying to manage your Sequence of Returns Risk through your asset allocation decision is a bit like trying to eat spaghetti with a spoon. It’s not the best tool for the job. If a spoon is your only option, it will have to do. Clearly, if you reduced your stock exposure—and thus your portfolio’s potential volatility—you would lessen your exposure to a negative sequence of returns. But this strategy does little to mitigate the real cause of the problem, and you are giving up higher potential returns that are critical to your portfolio’s longevity and standard of living in retirement.

The Right Tools for the Job

Use a fork instead. The harm that a negative sequence of returns can have is caused by having to sell and withdraw assets when values are down. The key is to have a game plan in place that allows you to avoid selling off assets at steep losses to fund needed expenses. Following are some strategies/tools made for this task:

Adequate Savings Buffer and Income Ladder

Having an adequate savings buffer combined with a 12- to 18-month income ladder to ride out the average recession will dramatically reduce the impact a negative sequence of returns could have on your portfolio. If you pre-fund 12-18 months of your income needs when markets are “high,” you will not be forced to sell off assets at a steep discount should markets fall suddenly in response to a negative economic event. Instead, you would simply cease buying new rungs on the ladder until markets recover.

Home Equity Line of Credit or a Pledged Asset Line of Credit

Having access to a Home Equity Line of Credit or a Pledged Asset Line of Credit (a brokerage-secured line of credit) can fund a “shock spending event” or income needed after your ladder runs out (assuming markets were still down). It is much better to pay a little interest expense for a brief time than to sell an asset at a 20%+ loss. Given bear markets have only exceeded 24 months one time since the Great Depression (during the 2000-2002 Dot Com Bust), you likely won’t need to borrow for long. Plus, interest rates are lowest at this point in the economic cycle as the Federal Reserve decreases rates to fight the economic downturn. Having access to a credit line to protect against a disaster can also reduce how much of a savings buffer you need to maintain, which means more can remain invested.

Rules-Based Flexible Spending Strategy

While not an easily implemented DIY solution, employing a rules-based flexible spending strategy that uses guardrails to inform when increases are allowed or decreases are needed will help you manage your SORR over the long term. You have no idea what path of returns you will be on during your 30+ year retirement. This is why a Monte Carlo analysis usually shows a very broad range of outcomes, spanning perhaps from running out of money too soon to passing away with more money than you started. A rules-based flexible spending strategy corrects the flawed Monte Carlo analysis assumption that changes couldn’t or wouldn’t be made along the way in response to what is happening in reality. A rules-based flexible spending strategy will ensure you make spending reductions in advance of reaching a danger zone while also ensuring you are increasing your spending along the way if you end up with a good path of returns so you can always make the most out of your retirement.

Most financial advisors focus on money management and “specialize” in accumulation. Little thought is given to strategies outside of the money management process. Retirement, or decumulation, is a different animal that exposes one to many new risks that must be identified and managed. I hope you have come to see there are better ways to manage your Sequence of Returns Risk than simply reducing your asset allocation to stock.

How do you plan to manage SORR as you get close to retirement? What other risks will you try to mitigate?