A cash balance plan is an amazing vehicle that allows high-income doctors to accumulate significant tax-deferred assets over a relatively short term.

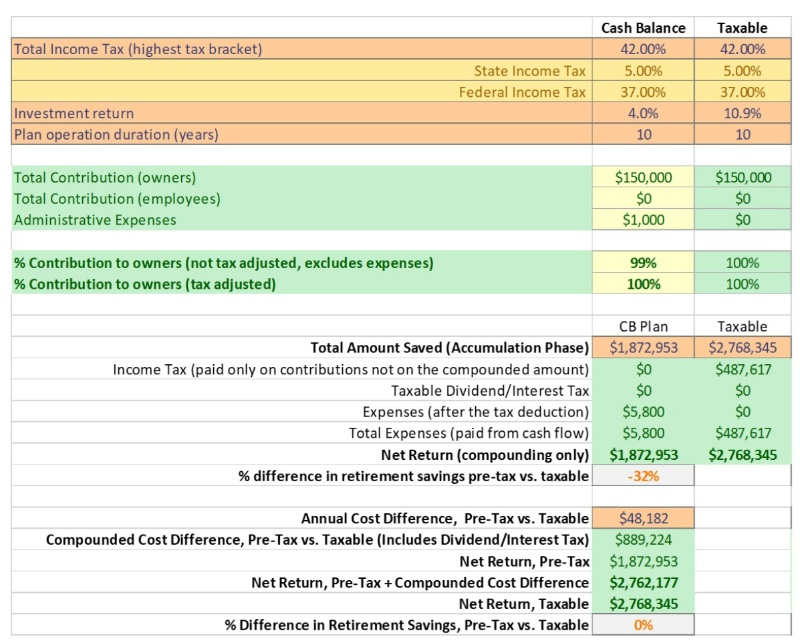

In 2025, a lifetime maximum for a 58-year-old is about $4 million, and this can be accumulated over a 10-year period. There are big advantages to maximizing tax-deferred account contributions for those in the highest tax brackets. It can be demonstrated (see chart below) that, over a 10-year period, a cash balance plan is very advantageous vs. a taxable account for those in the highest tax brackets. It would take an average taxable account rate of return of between 10%-12% to just break even with a cash balance plan with an interest crediting rate (ICR) of 4% (assuming 37% federal and 0%-10% state brackets). Moreover, there is a Roth conversion strategy that is available for those with high tax-deferred account balances, typically implemented in retirement, that can substantially decrease the tax liability while allowing massive Roth account growth, so having a large tax-deferred bucket is an advantage rather than a disadvantage vs. having all of the money in a taxable account.

The chart shows the break-even return calculation of a cash balance plan vs. taxable, with a generous assumption that no dividend/capital gains taxes were paid in the taxable portfolio. With taxes included, the break-even return could be as high as 12%. The annual cost difference accounts for the fact that additional money from cash flow was used to pay taxes. That could have been invested instead. Identical results can be obtained if the taxable contribution amount is decreased by the amount paid in taxes. This illustration assumes no NHCE employees, which is true for group practices where only partners are employed. For practices with employees, the analysis will need to include the extra employer contribution cost.

While a cash balance can be a great plan for the right type of medical or dental practice, there are several issues that can potentially make it a risky and costly investment. One of the most common scenarios in a group practice is when a partner leaves or retires. Everything is fine until they want to take a distribution. Things can go sideways when a distribution is requested if the value of plan assets has fallen significantly. Even if the plan was fully funded when the partner’s distribution account value was calculated, if at actual distribution time the value of plan assets falls, absent any planning, the plan sponsor would be liable for making up the shortfall. This means that the departing participant will get 100% of their account value, and the plan sponsor (all the partners) will contribute money to the plan to make up the losses. While this situation can be completely avoided, the practice leadership should have the knowledge to make sure this does not happen with some prior planning.

Another situation is an underfunded or an overfunded plan due to portfolio volatility. When a plan is underfunded, the partners must make up the difference in the year when the underfunding occurs. While this can sometimes be pushed into the next plan year, it is not advisable due to the potential snowballing effect. An overfunded plan has an opposite issue—if the return is higher than the crediting rate, the government, at plan termination, will end up taking 90% or more of the overfunded amount in the form of excise taxes. So, under some circumstances, overfunding could become an issue as well.

It is very common to see cash balance plan investments managed improperly. It is fairly common to see actively managed portfolios with lots of turnover consisting of multiple actively managed funds with high expense ratios or, worse, individual stocks or even illiquid investments that are hard to redeem quickly. For most cash balance plans, there is an additional Assets Under Management (AUM) fee applied to the plan assets. It is also quite common that the plan adviser is not an ERISA 3(38) fiduciary, so all the liability for investment performance falls on the shoulders of the plan sponsor. Most such advisers are not very knowledgeable about cash balance plans and how to properly construct the right type of portfolios that are appropriate for such plans. Because the majority of advisers charge AUM, some may even try to oppose reasonable strategies that reduce this AUM (and hence their fees), such as “terminate and restart” (discussed below) which can be a great tool to minimize plan risk due to portfolio volatility.

Due to the complexity of cash balance plans, there is a general lack of understanding of the inner workings of these plans by the plan sponsors who adopt them and by their advisers. This can lead to adverse scenarios that can easily be avoided with the right type of planning. In this article, we will review the cash balance plan basics and discuss ways in which the risk to the practice can be minimized by implementing advanced planning strategies—including how to handle distributions to departing partners when there is a shortfall, appropriate investment management to align with liabilities, and alternative plan design considerations (such as actual rate of return vs. fixed rate of return, PBGC vs. non-PBGC plan design, in-service distributions and “terminate and restart” strategy).

Cash Balance Plan Overview

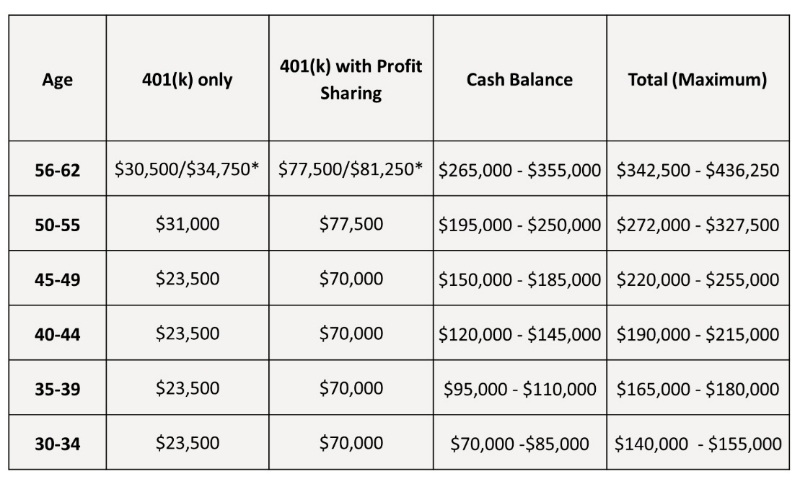

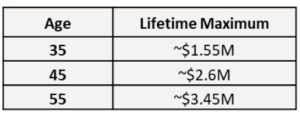

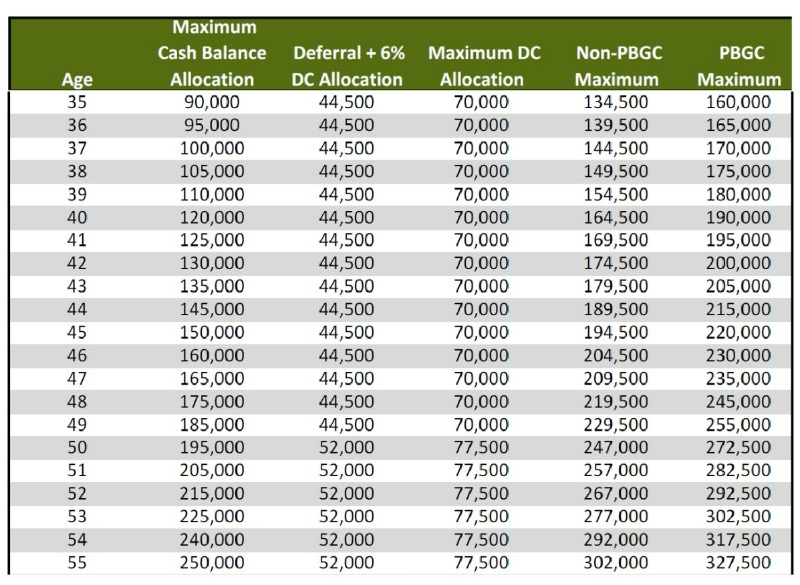

First, some key facts on how a cash balance plan works. A cash balance plan allows owners/partners to accumulate a lump sum based on their age and compensation. Partners/owners can specify their annual contribution amount based on their age and compensation (see chart above). Partner contribution is calculated using age and W-2, and it assumes a maximum plan duration of 10 years. At the end of the 10-year period, assuming that they’ve made maximum possible contributions, each partner will receive a lump sum known as their ‘lifetime maximum’ (see chart below). If the plan remains open after a partner has reached their lifetime maximum, they can only get the crediting rate, and no further contributions would be possible.Over time, your plan will be amended to allow for inflation adjustments, which means your final lump sum (and subsequent contributions) will be increased over the course of 10 years. These types of adjustments happen about once every three years.

Lifetime maximum amounts for 2025 (not including inflation adjustments).

Cash balance plans have a hypothetical crediting rate (aka ICR or Interest Crediting Rate), and participant assets are credited this rate each year. Cash balance plans are valued each year to be 100% funded. If the plan return is lower than ICR, the plan sponsor will make an extra contribution into the plan, and if the return is higher than ICR, the plan sponsor's contribution will be lower. In most cases, over 90% of the total plan contribution will be given to the partners/owners, so a small underfunding is fine, as most of the extra contribution is given by the partners to themselves.

A cash balance plan, first and foremost, is a way to lower your tax liability, and it should not be treated as an investment account. One thing to keep in mind is that it does not matter what the return on the assets is in a cash balance plan. This is because your lump sum distribution amount does not depend on asset performance. It only depends on age and W-2, and if one maximizes their contribution, this amount will be fixed. If the investment return is lower, your contribution will increase, and if it is higher, it will go down. After 10 years, the lump sum will be the same whether the assets returned 3% or 10%. In the case of a 10% return, this will significantly decrease the amount that can be contributed on an annual basis (or it can lead to eventual overfunding of the plan).

Given that we expect to pay out 100% of the assets to departing participants and on plan termination, having either not enough return (underfunding) or too much return (overfunding) is one of the biggest concerns that we must address. In the case of underfunding, we run into the issue of making distributions to retired/terminated participants who must receive 100% of their account value (as of the last valuation completed), so if the account value fell below that, the plan sponsor must make up the shortfall. In the case of overfunding, there are ways to use up the extra return up to a point, and this would require keeping the cash balance plan open. Some of this money can be moved to a 401(k), but no tax deduction can be claimed. And if the overfunding is high, it might take a long time to use up this money if all participants have already maxed out their CB contributions.

In short, having a rate of return higher than the plan’s crediting rate can lead to issues, and if the plan must be terminated for whatever reason, there is a possibility that any excess would be taxed by the government at a rate of 90% or higher.

More information here:

Cash Balance Plans: Another Retirement Account for Professionals

Top 10 Cash Balance Plan Mistakes to Avoid

Departing Partners with Large Balances

One of the biggest issues group cash balance plans will experience is when partners with large account balances leave the group and request distributions from the cash balance plan. Valuation is done for the prior year, so if, between Dec. 31 and the distribution time, the value of plan assets went down, the partners will still get 100% of their assets as of Dec. 31. The plan sponsor then would have to make up the difference, unless prior arrangements were made. This often comes as a surprise for both the plan sponsor and partners, but it should not be. This is a standard feature of cash balance plans. The only time it becomes an issue is when the assets of the partners who are leaving are significant ($500,000 or larger). This means that if a partner is leaving with $500,000, and the difference between the Dec. 31 valuation and the distribution time is, say, 10%, the plan is responsible for $50,000 since the partner will receive the entire $500,000 on distribution. If the distributed amount is higher, say $1 million, we may be looking at numbers in the $100,000 ballpark.

To avoid this type of situation, several steps need to be taken. The first step is to educate the partners and the plan sponsor on this type of scenario. The second step is to take action to implement an approach to mitigate this. One way to do that is to include specific clauses in the partnership agreement, where each partner is obligated to make up their own portion of the shortfall to the plan. The partnership agreement can be amended to provide for an additional contribution to be made by departing partners when necessary to fund the plan for distributions. The third step is to ensure that when the partner leaves the practice, there is money left over to cover any shortfall, whether via a plan contribution or outside of the plan. The details of this arrangement can be worked out by both ERISA and practice attorneys.

While there may be concerns regarding ERISA vs. contract law enforcement, it is better to be proactive than end up holding the bag when no planning is done to mitigate this type of scenario.

Minimizing the Risk to Your Plan

Groups can take additional steps to minimize the risk to their plan and to ensure that the plan is managed prudently, and we’ll consider each of these points in more detail below:

- Implement a low volatility portfolio.

- Consider an actual rate of return (ARR) plan, where only shortfalls below 0% are made up at distribution (so if your plan has a high crediting rate, the difference can be lower if you only make up the loss up to what you have contributed, not up to the crediting rate). This type of plan design is not for every practice, but this can also mitigate the requirement to make up the shortfall up to the crediting rate by remaining partners. Not everyone wants to increase contributions during down years, and this can potentially address that issue.

- Consider terminating and restarting your cash balance plan if it has been around for at least 7-10 years.

- Amend the plan document to allow for in-service distributions to participants starting at age 59 and ½.

Portfolio and Funding Volatility Explained

The underlying cause of many of the issues faced by the practices that adopt a cash balance plan is portfolio volatility. There is a general misunderstanding of how this affects many aspects of the plan’s operation, including funding volatility, distributions to partners, and plan termination. Higher volatility simply means a larger range of expected plan returns. Quite often, the Interest Crediting Rate (ICR) for many older cash balance plans is 5%, and many advisory firms build stock-heavy portfolios trying to match the ICR with returns. This comes from the mistaken belief that portfolios should be constructed to “match” or “beat” the ICR.

In cash balance plans, that’s not how things work. Volatility can easily result in an underfunded or an overfunded plan, and this can adversely impact the plan’s operation, including forcing the plan to make up losses while providing distributions to departing partners (if arrangements have not been made to mitigate this) and potentially having issues with plan termination. Cash balance plans for smaller practices typically last for 10 years, but for larger practices, they can last a lot longer than that if there are enough partners who can still participate (and if there is at least 40% participation, which is a key requirement for any cash balance plan).

However, there are many scenarios under which cash balance plans must be terminated relatively quickly without much notice. Mergers, dissolutions, and adverse business conditions are some of the reasons cash balance plans can be terminated early, which can result in asset liquidation under potentially unfavorable circumstances. Underfunding would lead to potentially large contributions, while overfunding can lead to excise taxes on any gains above the ICR (especially if there is no ability to use up the gains over time). All these issues are caused by excessive and unpredictable volatility. Thus, avoiding volatility as much as possible is the name of the game here, as this will minimize the risk to the plan.

Stocks introduce extra volatility, which means that if we want to minimize our risk, stocks should be avoided at all cost. What about matching the ICR, you might ask? Even if we really tried, there is no way anyone can match an ICR without using illiquid and/or complex investment products. Average returns even for the least volatile portfolios of bond funds will have a spread around the ICR that we cannot control. What we can control is how big this spread is, and while we can attempt to minimize it, we cannot guarantee that our average return will be exactly ICR. That, however, is not an issue if we have the lowest possible volatility. Having some underfunding or some overfunding is acceptable if it is relatively small and does not cause the same issues as large underfunding and overfunding (several percentage points vs. 10%+, for example).

Funding volatility happens when differences between portfolio returns and ICR necessitate extra contributions (or diminish your available contribution amount), and this is amplified as individual account balances reach $500,000 and above. If your account balance is $1 million, a 5% underperformance relative to the ICR will result in an extra $50,000 contribution, while a 5% outperformance relative to ICR will diminish one’s potential contribution amount by $50,000. A higher ICR will result in a larger funding volatility, and so will a high volatility investment portfolio. Funding volatility is especially an issue when there is underperformance.

A plan can be frozen if the group does not want to make up the shortfall in the same year, but if underperformance continues, this can snowball into a larger shortfall. Funding volatility is a significant issue that must be addressed thoroughly so that it does not become a problem later once the assets in the plan grow.

More information here:

Comparing 14 Types of Retirement Accounts

Portfolio Design to Minimize Funding Volatility

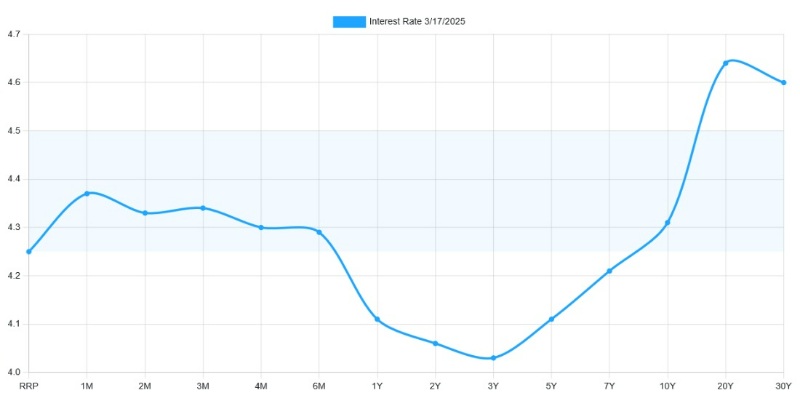

US Treasuries yield curve example (2025). Note how the yield curve is inverted, with shorter maturity bonds yielding more than intermediate maturity ones.

Now that we have established that volatility is not our friend and that we are not rewarded for beating the crediting rate, especially when the downside is very likely, the question is: what should our portfolio look like?

Here are the design constraints for an ideal cash balance plan portfolio:

- While a typical small practice cash balance plan has a hypothetical 10-year horizon, this type of plan is often terminated with very little notice.

- We should invest in such a way as to minimize drawdowns, and we should attempt to insulate our portfolio as much as possible from market fluctuations.

- Our portfolio should provide a consistent return that is relatively steady.

- Drastic changes in interest rates should not affect our portfolio in a major way.

It is quite clear that, with these constraints, stocks will not add any value to this portfolio because they will make it less predictable and more volatile. Bonds should also be selected carefully. Duration is a measure of bond risk, and bonds with higher duration lost 10%+ in 2022 when interest rates rose quickly. From the chart above, it is obvious that, at least in 2025 (if the yield curve remains the same), we can stick to the shorter end of the yield curve without having to take extra risk to get more yield.

One big risk for any portfolio that has bonds in it is the interest rate risk. Thus, a laddered bond portfolio should be designed to withstand big changes in interest rates. When interest rates go down, the price of bonds goes up, and when bond prices fall due to interest rates going up (which is what happened in 2022), we expect our portfolio to fall a lot less than the total bond market index because we do not have much exposure to the longer maturities or corporate bonds. Still, such a portfolio can drop as much as 3%-4% in a relatively short period of time (compared to 10%+ for many other bonds, including the total bond market index).

Due to the volatility experienced in 2022, this is the best approach, given how short our horizon is. On the other hand, your 401(k) plan could be invested as riskily as you would like, given that the cash balance plan is all bonds. You can consider your cash balance plan as your bond allocation, and you can build up your 401(k) and taxable allocation to be more aggressive. This way, we get the best of all worlds, and you get your cash balance plan working as a tax shelter rather than as a speculative investment that can make your life harder than it has to be. After about 10 years, you could move the cash balance plan investment into a 401(k) plan and rebalance into a more aggressive allocation.

Fixed vs. Variable/Actual Rate of Return (ARR)

So far, we have discussed a fixed crediting rate. While a fixed rate of return plan has a crediting rate between 3%-5% (with the rate typically being set between 3%-4%), some might want to have a higher rate of return than that. Others might want to decrease the funding volatility and address the issues related to paying out terminated participants when the plan portfolio has a loss. There is another type of crediting rate called actual rate of return, aka market return, where the investment return can be variable. There is a lot of misunderstanding about this type of plan.

Here are some key points regarding the actual rate of return plan.

- The annual interest crediting rate will be an actual rate of return up to 5%. There are some plans with rates as high as 6%, but those are very rare.

- When the return is less than 5%, it will be allocated in proportion to the starting account balances.

- A participant's distribution cannot be less than the sum of the total allocations, and this is only applied at distribution.

- The only time the plan would be considered underfunded would be when the cumulative return is negative and you are looking to pay out a participant.

- There will be only a single annual valuation and returns will be allocated at the end of the year, so the assets do not accrue credits until the end of the year valuation (vs. a fixed crediting rate where interest is accrued throughout the year). This means that any distributions will be taken at the beginning of the year, and not throughout the year (as is possible in a fixed rate of return CB plan).

- If the return exceeds 5%, the overfunded amount can be used to offset future contributions. If the overfunding becomes sizable, the plan can be amended to allocate the excess among the partners. With large overfunding, we are still in the same domain as with fixed rate plans—too much of an overfunding in a terminating cash balance plan that is maxed out will lead to potential excise tax issues.

At first glance, this type of plan allows for a higher rate of return (typically capped at 5%), and participants do not have to make extra contributions into the plan even with a return below 0%. However, when distributions are made, participants simply get the sum of their credits/contributions at whatever return the plan portfolio produced. This eliminates the funding volatility (as the only time the plan is underfunded is when the return goes below zero) and this also avoids the issue where a participant gets 100% of their account value and must make themselves whole if the distribution amount is less than the valuation amount.

Some might think this type of plan would allow for higher risk-taking to potentially get a higher rate of return. In fact, it is the opposite: given the higher uncertainty, we should be a lot more careful since taking too much risk can result in a lower pot of money after 10 years. While we can potentially get as much as 5% return if we are lucky, we can also have a negative return if we're unlucky. If a higher-risk portfolio is used, volatility will go up, and we might end up with a lot less money than with a fixed rate of return that uses a low volatility bond portfolio.

Ten years is not a particularly long-term investing horizon, so anything can happen. It also turns out that due to testing complexities, actual rate of return works only when partners/owners are the only ones participating in a cash balance plan. Given all the above, when presented with the fixed vs. variable options, many plan sponsors opt for a lower fixed ICR vs. a higher variable one.

In-Service Distributions

Another good way to lower the risk of your cash balance plan is to allow in-service distributions to participants who are at least 59 ½. Typically, any participant who is 62 years old can request in-service distribution of their assets into a 401(k) plan. This is a good idea because many older participants will more than likely have larger account balances, so if they can move their money to their 401(k) plan or an IRA, this will keep the assets in the plan from growing too rapidly.

Another option is to allow in-service distributions at age 59 ½. This usually requires the plan to be funded at 110%, but this is not an issue, as actuaries have different ways in which to arrive at that number without requiring much, if any, additional money to be contributed. These types of distributions are typically allowed to be made once a year, and the logistics would be provided to the plan sponsor by the actuaries.

PBGC vs. Non-PBGC Cash Balance Plans

PBGC vs. non-PBGC contributions (2024). The main difference is the 6% profit-sharing limitation in a non-PBGC covered cash balance plan.

This is a topic that always comes up with smaller practices—especially when the practice has fewer than 25 partners and staff or if the potential cash balance plan will have fewer than 25 participants even if the practice is larger. Once there are more than 25 participants in the plan, it is covered by PBGC (Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation). This coverage continues even if the number of participants becomes less than 25 in the future. As a result of PBGC coverage, two things happen: 1) annual premiums are paid to PBGC (a $106 flat rate or a $52 variable rate per participant in 2025), and 2) maximum profit-sharing (PS) contribution is possible in the 401(k) plan (up to $70,000 in 2025). Absent PBGC coverage, 401(k) profit-sharing allocation is usually limited to 6% (as you can see in the chart above).

In 2025, for example, 6% PS would be $21,000 based on $350,000 compensation, so the maximum 401(k) and PS contribution would be $44,500. Maximum PS would be about 13% in a PBGC-covered plan. This is about a $25,500 difference, and some partners may be unhappy if they cannot max out their PS. In addition, there may also be some partners who do not want to participate in the cash balance plan but who would still want to max out their 401(k) contribution. There are several options to handle this in a group that will have fewer than 25 participants.

If the group is never going to get to 25 participants and there are only partners in the group, the Mega Backdoor Roth would be an option. In this case, $25,500 can be contributed via after-tax and converted to Roth inside the 401(k) plan. Alternatively, those who only want to contribute the 401(k) maximum of $70,000 may simply contribute the difference to the cash balance plan. This may be less than ideal, but it is still an option.

If the group has more than 25 partners and/or staff, it may be possible to make the plan into a PBGC by bringing several partners and/or staff into the plan to get at least 25 participants. This can be achieved by giving those participants a meaningful benefit, which for partners can range from $5,000-$20,000, depending on demographics. This is a relatively small price to pay to make sure that all participants can max out their 401(k). If the plan has at least 25 participants and all these participants stay in the plan for three years, “meaningful benefit” participants can simply stop contributing, and the plan still retains PBGC status with the maximum 401(k) contribution option for all participants.

More information here:

The 15 Questions You Need to Answer to Build Your Investment Portfolio

Plan Termination and Restart

If your group has had a cash balance plan for at least five years, you probably wondered whether you can somehow get the money from the cash balance plan into your 401(k) plan. There is a strategy known as “terminate and restart,” and it is a legal strategy provided that several key conditions are met. First, there must be substantial changes to the plan design, and second, the plan must have been around long enough so that the actuaries are comfortable terminating and restarting it.

There are two major reasons to terminate and restart your cash balance plan. No. 1 is the desire to move your money from your cash balance plan into your 401(k) plan for a potentially higher rate of return. No. 2 is to minimize the funding volatility risk, which becomes a real concern once the assets in the plan grow. Even with a conservative portfolio, funding volatility can still be a concern once the plan has been around for a decade or longer. Unfortunately, neither of these is a valid reason to terminate and restart the plan.

Some of the valid reasons for terminating and restarting your plan include changing the plan’s interest crediting rate, redesigning the plan due to a major shift in demographics, and merging with another practice. Some practices may have more than one opportunity to terminate and restart, but this is not something that is guaranteed for each practice. In general, this strategy can be implemented closer to the 10-year mark than to the five-year mark. While terminate and restart is a viable and legal strategy, one thing is certain—there is no way to put this on a schedule (such as terminating and restarting every five years).

There are several practical reasons for changing the design of your cash balance plan. Some plans are designed with a high fixed rate of return (typically around 5%), so to decrease potential funding volatility in the future, a lower fixed rate (between 3%-4%) can be selected. If the plan is not individually designed and has contribution ranges with caps for all participants, this may be a reason to redesign the plan to allow participants to maximize their contributions. Some plans can be designed with an actual rate of return if the demographics are favorable. At this point, it should be clear that having a lower crediting rate does not mean that you are somehow getting a lower return on your investments. Your lifetime maximum is in no way affected by the crediting rate, so the only reason to go with a lower rate would be either to allow for a more favorable design (especially if you have staff) or to have a lower rate to minimize funding volatility in the future.

The Bottom Line

A cash balance plan is a great tax shelter for high-income doctors, but because most of these plans are set up by actuaries who have a very narrow focus or advisers who may not have the best understanding of how cash balance plans work, plan sponsors need to get a better idea of what is involved and how to avoid the types of issues that can potentially prove costly.

Each practice may have different needs and demographics, so it is important to make sure that your plan is designed with your practice’s best interests in mind. Your practice might be a good candidate to terminate your plan and start a new one that is redesigned to better fit the needs of the practice. It is doubtful that anyone would object to making changes to the plan if the interests of all partners are protected. It is also important to educate any current and incoming partners about their obligations under your plan to make sure that all partners are aware of the benefits and the risks.

It is always a good idea to select independent service providers who can advise the plan sponsor on the best plan design for the practice and who can also provide fiduciary advice to the plan sponsor on all aspects of their retirement plan needs. Especially for larger practices, it is critical to manage future risk by taking the steps outlined above. It should not cost extra to implement and maintain a top-notch cash balance plan—most of the best strategies described in this article should be part of the standard set of services and advice your plan should receive from your service providers.

Have you used a cash balance plan? What were the pros and the cons? Would you use one again if given the chance?