I've been telling people to “Live Like a Resident” since at least 2011, and while I do not claim to have come up with the phrase, I'm pretty sure I'm almost singlehandedly responsible for popularizing it. I was even pleased to hear Dave Ramsey using it recently on his show. However, we get enough pushback on it that it made the list of The White Coat Investor's Most Controversial Teachings.

Apparently, some people really don't like hearing that phrase. Perhaps most prominent was a thread from the WCI subreddit. The funniest part about that thread was the reaction to it on the WCI Forum. Reddit skews younger (mostly Gen Z and Millennials), while forums and Facebook groups skew older (mostly Gen X and Boomers). The whole discussion basically devolved into the Boomers/Xers saying the Millennials/Zers were lazy, undisciplined bums, and the Millennials/Zers saying the Boomers/Xers were out of touch and could have bought mansions for less than $500,000 while the younger generations can't even get a condo for less than seven figures.

What Does Live Like a Resident Mean?

Live Like a Resident (LLAR) is a principle, not some sort of exact prescription. It's a recognition that the greatest wealth-building tool for high-income professionals, like doctors, is their income. Harnessing this tool and turning your high income into wealth (i.e., a high net worth) is the key to financial success. No matter who you are, when it comes to personal finance, the secret to success is to spend less than you earn and to take the difference and use it to accomplish your financial goals like:

- Paying off debt

- Investing for the future (spending less now so you can spend more later)

- Buying stuff and experiences you want

- Giving to people and causes you believe in.

LLAR is a recognition that the easiest time to use a massive chunk of your income to build wealth is in the beginning, before you get used to the income. It's a behavioral finance thing. Last year, you lived on $60,000 because you made $60,000. What would happen if you STILL lived on $60,ooo while earning $360,000? Good things, most likely. Even with a higher tax burden ($100,000?), there would be $200,000 that could be used for a down payment on a dream home or to wipe out half (or even all) of your student loan burden or to catch up to your college roommates as far as retirement savings.

LLAR is a recognition that half of American households live on an income less than that of a resident. It's not some sort of a vow of poverty.

LLAR is a recognition that the first dollars you save are the best dollars, since they have the longest period of time for compound interest to work on them.

LLAR is a recognition that medical school is still a wise investment, even if you have to pay for the whole thing with borrowed money, because you can wipe out that debt quickly by LLAR after training.

Who Doesn't Have to Live Like a Resident?

So, who doesn't have to live like a resident? There are really three things to discuss here.

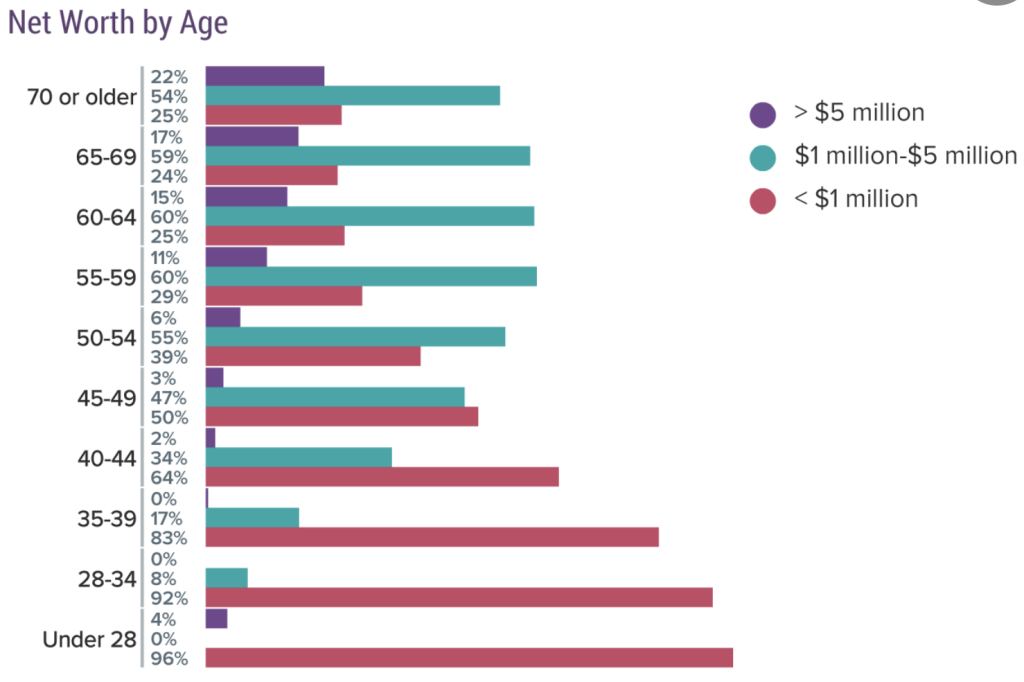

First, nobody HAS to live like a resident. It's always been optional. It's your money. Do whatever you want with it. If you want to live your whole career with financial stress and have a less-than-comfortable retirement, that's your choice. Physician net worth surveys repeatedly show that about 1/4 of doctors in their 60s aren't millionaires, and about 3/4 of them aren't pentamillionaires. Here's an example of one of those surveys:

What does it take to be a pentamillionaire? It takes saving $75,000 a year for 30 years and earning 5% real on it.

=FV(5%,30,-75000) = $4.98 million

That's it. And that's just the investments. After 30 years, most doctors also have a lot of home equity and a whole bunch of stuff. Yet 3/4 of doctors don't get there. In fact, over 10% of them don't even have a net worth of $500,000 by retirement time. But hey, do what you want with your money. Who cares that you're starting a decade later than your college peers and $300,000 behind the starting line? I'm sure you'll be fine. You'll make up for it somewhere down the line, I'm sure.

Did I lay on that sarcasm thick enough? Good.

But my point remains that I don't know any doctors who lived like a resident for 2-5 years that didn't end up in that top quartile (pentamillionairehood). I'm sure it's possible to get there without LLAR, but why chance it when it's practically guaranteed by doing so?

The second point is that NOBODY actually lived EXACTLY like a resident. We all spent a little bit more. The point of LLAR is to avoid the lifestyle explosion that typically accompanies an increase in income from $75,000-$400,000. Plenty of docs commit themselves to that new lifestyle before they even receive a single attending paycheck with a big fat mortgage and a couple of Tesla payments. Then, a few months later, when their student loan payments balloon, they find themselves living hand to mouth on $250,000, $350,000, $450,000, $550,000, or more. That's not a good feeling.

But almost no one ACTUALLY lives the exact lifestyle they had as a resident. Most of us gave ourselves a little raise. Heck, a 50% raise would be huge in corporate America, but it probably still qualifies as living like a resident. If you're earning $300,000 gross ($225,000 net) and you increase your spending from $60,000 to $90,000, you've still got $135,000 with which to build wealth. You can do a lot with that. But diets don't work if you're hungry, and LLAR doesn't work if you're feeling financially deprived. You've got to spend enough that you don't feel like you're making some huge sacrifice.

The final point is that the LLAR period is supposed to be short. In our case, it was four years, precisely the amount of time I owed the Air Force for paying for my medical school. In general, that period of time should be between 2-5 years. Not forever. If you're still LLARing at 45 (or maybe even as young as 35 for traditional students who did short residencies), you missed the point. The better your financial situation, the shorter your LLAR period should be. Ask yourself, “Where do I want to be when my LLAR period is over?” You get to choose, but a typical doc might say, “I want to accomplish the following during my LLAR period:

- Boost my emergency fund to $40,000

- Pay off my student loans

- Have a nest egg of $250,000

- Be living in a ‘doctor house' (define that however you like).”

Then you just adjust the length of the period to your own financial circumstances.

Owe $400,000 in student loans and work in a $250,000 private practice job in an HCOL area? You probably need five years. Parents paid for school and gave you a $250,000 20s fund, and you're making $800,000 in a medium-sized town in Indiana? You may not even need two years.

More information here:

Living Like a Resident Is the Answer

A Financial Love Letter to My Wife (and the Realities of Living Like a Resident)

Factors That May Affect Your LLAR Period

Multiple factors can shorten or lengthen your LLAR period. It's even possible to shorten that period to zero years, although I think there are still some behavioral finance benefits to having at least a short one—even if it is not mathematically necessary. Here is a list of factors to consider:

- Income (The more you make, the more you can spend while still rapidly wiping out loans and building a nest egg.)

- Size and interest rate of student loan burden (The more you owe and the higher the rate, the longer it takes to pay them off.)

- Eligibility for PSLF (PSLF eligibility is an awful lot like having your parents pay for most of school.)

- Cost of living (Higher tax rates, and especially higher housing costs, prolong the wealth-building process.)

- Spousal income (A resident married to an attending four years out may never have a LLAR period.)

- Actual or planned inheritance (If you're already wealthy, you don't have to work as hard to get wealthy.)

- Previous career/wealth (It works similarly to an inheritance.)

- Length of career (Yes, saving “just” 20% into boring old index funds should make you a pentamillionaire, so long as you can do it for three decades. No burnout. No disability. No change in your passion level. No desire to go part-time or on the parent track for a few years. Or maybe you should just hedge against some of those risks by LLARing for a few years and front-loading some of your lifetime financial tasks.)

- Number of dependents (Children, parents, and others all count.)

I still recommend docs have an LLAR period after training. But life is a Choose Your Own Adventure book. You get to choose how long your LLAR period is, and you get to choose how extreme it is.

What do you think? Did you LLAR? What did that look like? How long did it last? Are you glad you did it?