Have you ever looked at a Monte Carlo analysis of sustainable retirement spending and thought to yourself, “How could there be so much variability in potential outcomes?” That might especially be true given that the same asset allocation (or mix between stocks and bonds) drives the results.

A $20.8 Million Dispersion in Outcomes

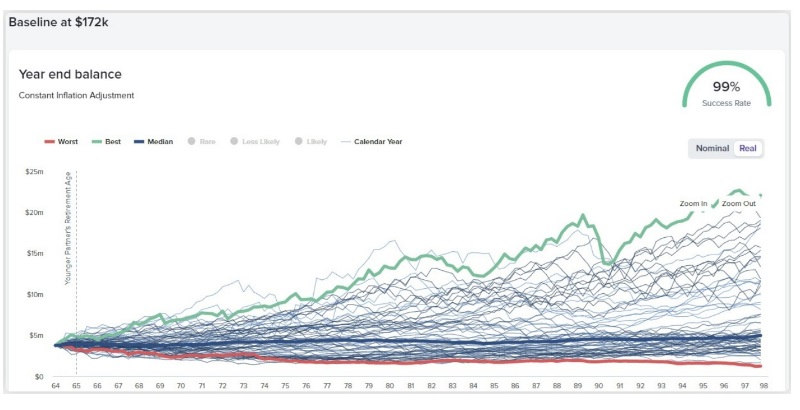

Here is an example of a 64-year-old couple with a $4 million portfolio (60% stock/40% bond) who plans to retire at age 65 and spend an inflation-adjusted $172,000 after-taxes per year from Social Security and portfolio income and withdrawals:

At a 99% probability of success rate (which is far too high, by the way), the variability of outcomes is striking. The worst-case actual historical observation (having started this retirement in November 1936), indicated by the red line, shows this couple would have passed at 98 years old with $1.22 million (real, inflation-adjusted dollars). The best-case actual historical observation (having started this retirement in July 1982), indicated by the green line, shows this couple would have passed with $22.03 million. This is a $20.81 million difference in possible outcomes based on actual historically experienced sequences of returns.

The standard of living that could be afforded in retirement under these different outcomes is wildly different. While we cannot know in advance the path of returns we will be blessed with during our retirement years, your choice of withdrawal strategy in retirement can have an enormous impact on your dispersion in outcomes and the quality of life you can lead while retired.

More information here:

The 4% Rule and Safe Withdrawal Rates

4 Methods of Reducing Sequence of Returns Risk

Total Return with Rebalancing (the Conventional Way)

The example presented illustrates a “total return with rebalancing” withdrawal strategy. It is, by far, the most prevalent strategy used by financial advisors and DIYers alike. This strategy chooses an asset allocation (typically a mix of stocks and bonds) based on a retiree’s goals and risk profile. Systematic withdrawals (e.g., monthly) from the portfolio, often based on maintaining a “safe withdrawal rate,” are funded by a combination of income, capital gains, and principal. The portfolio is rebalanced back to the target asset allocation on a pre-determined basis (quarterly or annually) by selling investments that have grown in value and reinvesting the proceeds in the investments that haven’t.

Total return with rebalancing is an easy withdrawal strategy to implement and delivers a predictable retirement “paycheck” because it is often based on a static withdrawal rate. It also captures the benefits of rebalancing, a forced mechanism to sell high and buy low consistently—one of the hardest things to do as an investor.

Despite its benefits, this approach has several significant shortcomings:

- It overly relies on asset allocation as the lever to control the sequence of returns risk (see our previous WCI guest post entitled “The Folly of Relying on Asset Allocation to Manage Sequence of Returns Risk”).

- It requires conservative asset allocations paired with static “safe” withdrawal rates, which tend to lead to underspending in retirement. Whether the couple in our example ended life with $1.22 million or $22.03 million, they never enjoyed spending or gifting more than $3.59 million from their portfolio while living.

- The steady, inflation-adjusted retirement “paycheck” approach does not mesh well with retiree spending research, showing that inflation-adjusted spending tends to decline over the course of retirement (J.P. Morgan Asset Management, David Blanchett, and more). In this case, steady spending leads to less available spending early in retirement when you're healthy and can enjoy it most and it provides more than needed later in retirement.

- It relies on “probability of success” as its measure. Is an 80%-90% probability of success suitable? What does it mean to fail? Is any probability of failing retirement even really acceptable? The point is that total return with rebalancing attempts to find the maximum safe withdrawal rate corresponding to the probability of success you’ve chosen and locks you into that level of spending, assuming you can’t (or won’t) change over a 30+ year retirement regardless of what actually has happened or is happening. The higher the probability of success you choose, the lower your withdrawal rate and the more you possibly leave on the table upon passing. This is why a 99% probability of success would be considered way too high. A 99% probability of success would have to set your sustainable spending so low that it could pass even the worst-case scenario (even though it is not probable).

- It fails to incorporate reality as it unfolds. If you found yourself on a great path of returns during the first 10 years of retirement and had twice what you started with, wouldn’t you want to increase spending and/or gifting? We have a lot of clients who have a secondary goal of gifting to their children once they know they are not at risk of becoming a financial burden to them. If we experienced a second Great Depression, would you not curtail your spending—at least some—out of fear?

The total return with rebalancing withdrawal approach is a great way to provide a stable cash flow in retirement and to maximize the amount of inheritance for your heirs, but it’s not the best way to maximize the joy you could derive from your wealth while living—whether it's through travel, shared experiences, or gifts you get to see enjoyed.

Bucket Strategy (or Time Segmentation)

The bucket strategy allocates money based on asset-liability matching, which matches future investment sales with planned expenses. Generally, there are three “buckets,” which can be separate investment accounts. As with all strategies, there’s leeway in how they’re designed.

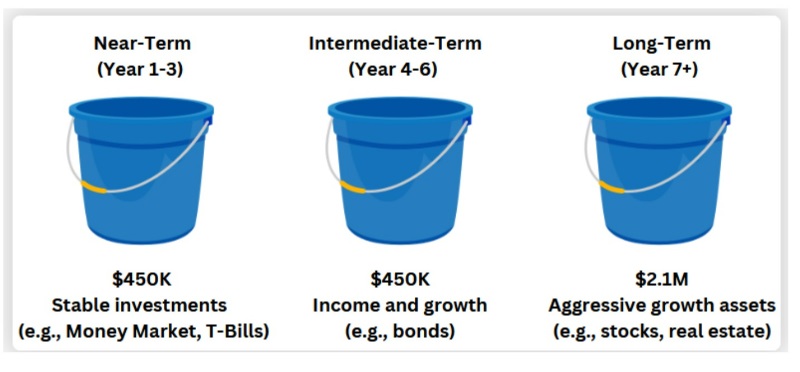

Here is an example of how a retiree with a $3 million investment portfolio could allocate their account if they planned on withdrawing $150,000 annually.

The near-term bucket would have the first three years of retirement spending invested in stable investments, like a money market fund and Treasury bills. The intermediate-term bucket would have the next three years of spending in investments that provide income and growth, like bonds. And the long-term bucket would be designated for your spending needs seven years out and beyond, invested aggressively for growth in stocks and real estate.

A significant benefit of bucketing is that it’s easy to understand and it plays nicely with our tendency to mental account. This helps retirees feel comfortable spending, which can be challenging during early retirement and heightened market volatility. It’s also customizable based on preferences (e.g., the near-term bucket can be extended to five years of spending for the risk-averse), and having a near-term bucket helps mitigate the sequence of returns risk.

But does bucketing help retirees avoid making unnecessary sacrifices? We don’t think so. Bucketing is really just total return with rebalancing in disguise. If we add the buckets in our example, we get a 70% stock/30% bond asset allocation. So, bucketing strategies suffer the same shortcomings as a total return with rebalancing withdrawal strategy.

Additionally, bucketing adds complexity to the rebalancing decision, as rules need to be created to “refill” the buckets. If buckets are not refilled, your investment portfolio becomes increasingly aggressive as you spend down your near- and intermediate-term buckets. And since rebalancing calls for selling growth assets to buy stable assets, some of the benefits of traditional rebalancing, where assets are sold based on how they have appreciated in value relative to other portfolio assets, can be lost.

Dynamic Withdrawal Strategies (or Flexible Spending Rules)

Dynamic withdrawal strategies create spending rules designed to change retirement income distributions based on actual market performance. Dynamic withdrawal strategies solve for the shortcomings presented by the total return with rebalancing and bucketing strategy approaches. Dynamic withdrawal strategies allow a retiree to start with an initial withdrawal rate exceeding the “safe withdrawal rate” allowed in the others because mid-course corrections can and will be made during bad and good markets as needed or allowed. Dynamic withdrawal strategies also provide comfort that a retiree won’t run out of money in retirement because changes will be required long before that can happen.

The tradeoff is that dynamic withdrawal strategies require a retiree to accept some level of variability in their retirement income. How much variability a retiree is willing (and able) to accept will be determined by an individual’s situation and the extent to which fixed expenses are covered by non-portfolio income sources (i.e., Social Security, pension, etc.). The good news is that most dynamic withdrawal strategies are customizable, and they can fit income variability and floor constraints.

The most popular form of dynamic withdrawal strategy uses rules to set upper and lower “guardrails” around some measure, typically withdrawal rate or portfolio value. The upper guardrail serves as the “prosperity rule,” when an increase in your withdrawal is warranted because the portfolio value exceeds the upper guardrail. The lower guardrail serves as the “preservation rule,” when a decrease in your withdrawal is required because the portfolio value fell below the lower guardrail. These guardrails keep a retiree on track and serve as signals when an increase in retirement income is warranted or when a decrease in retirement income may be necessary. Dynamic withdrawal strategies help retirees consume their portfolios more efficiently because they factor in both portfolio performance and spending (not just spending).

More information here:

Fear of the Decumulation Stage in Retirement

A Framework for Thinking About Retirement Income

What the Research Shows About Retirement Drawdown

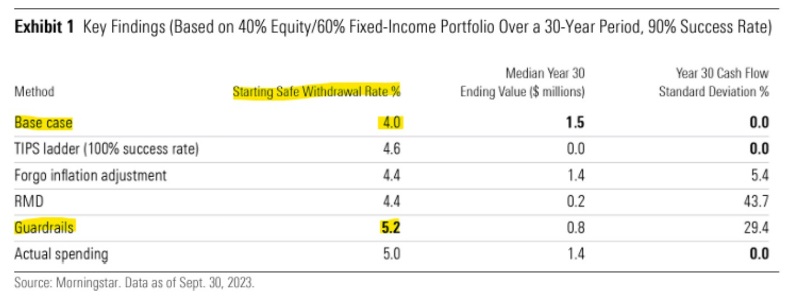

Morningstar provides some insightful findings in its research paper, “The State of Retirement Income: 2023,” as researchers modeled the safe retirement drawdown rate for 2023 (i.e., total return with rebalancing strategy) and then compared it to five other retirement withdrawal strategies. A summary of their key findings based on a 40% stock/60% bond portfolio over 30 years at a 90% probability of success rate follows:

The “Base case” method represents the conventional total return with a rebalancing and inflation adjustment approach. The “Guardrails” method is based on the popular Guyton-Klinger approach (more on this later). Morningstar’s research found that the guardrails dynamic withdrawal strategy provides the highest starting safe withdrawal rate at 5.2%. The guardrails approach provides 30% more retirement income than the total return with rebalancing approach, which over 30 years means a much higher quality of life and level of enjoyment. The cost for this higher starting withdrawal rate is a lower median Year 30 ending value (at $800,000 vs. $1.5 million) and greater cash flow volatility. Still, this tradeoff is well worth it for the vast majority of retirees we work with who would rather spend more while living and who can enjoy it or gift it while they can still see the benefit rather than having wealth transfer at death (even if a little more wealth could be transferred).

Dynamic withdrawal strategies are one of the most powerful tools retirement planners have in their tool chest. Vanguard, in its “Advisor’s Alpha,” and Morningstar, in its “Alpha, Beta, and Now . . . Gamma” research papers, both point to the material value of dynamic withdrawal strategies. Morningstar even goes so far as to say dynamic withdrawal strategies can create more value than all of the tax-management strategies combined (fortunately, these things aren’t mutually exclusive because we believe in both strongly and apply both in practice).

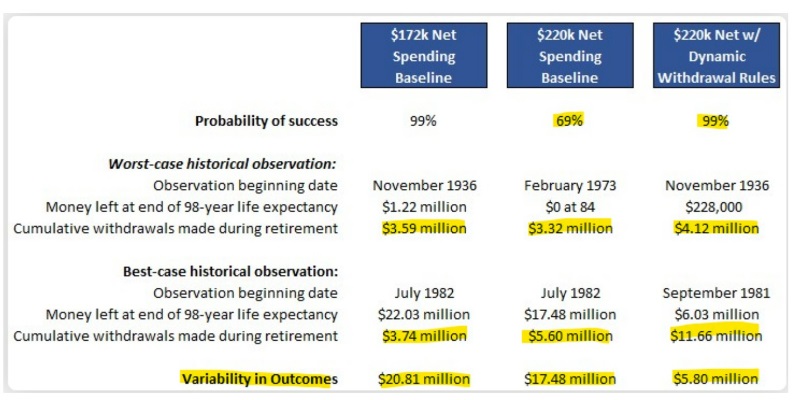

Expanding on our earlier example of a 64-year-old couple with a $4 million portfolio (60% stock/40% bond) who plans to retire at age 65 and spend an inflation-adjusted $172,000 after-taxes per year from Social Security and portfolio income and withdrawals. Following is a summary of the effects of raising their spending target to $220,000 after-taxes per year and the further effect of then overlaying on a dynamic withdrawal strategy:

The probability of success goes from dropping to 69% to improving to 99% (recall, dynamic withdrawal rules will require changes far before risking failure). Most importantly, cumulative withdrawals made during retirement are the highest under any scenario. The variability of outcomes narrows substantially, because you are spending/gifting more during retirement when you can.

More information here:

I’m Retiring in My Mid-40s; Here’s How I’ll Start Drawing Down My Accounts

Guardrails Strategies in Practice

If a guardrails strategy is so great, why doesn’t everyone use it? Short answer: they are challenging to implement in practice. Most guardrail rules are based on withdrawal rates (including the most popular guardrail strategy, Guyton-Klinger). Withdrawal rate-driven guardrail strategies are problematic because they rely on steady portfolio withdrawal rate patterns that seldom occur in reality. Your portfolio withdrawal rate (especially in earlier retirement) can jump around based on your sources and needs for retirement funding. For instance, perhaps you are two years away from claiming Social Security, so you need to take more temporarily from your portfolio until benefits kick in (i.e., take a higher withdrawal rate). Perhaps you are executing a Roth IRA conversion strategy requiring greater funding to meet temporarily higher tax liabilities. Of course, less would be needed later as tax liabilities drop. Withdrawal rate-driven guardrails, like Guyton-Klinger, don’t play nicely with these external realities.

The good news is that risk-based guardrails are an alternative approach that solves the withdrawal rate-driven guardrail shortcomings. The bad news is that it is even harder to implement without access to specialized retirement planning software. Shifting from withdrawal rates to risk provides a more holistic approach to spending adjustments that allow us to apply guardrails to the type of unique spending profiles we typically see in reality.

While a complete examination of risk-based guardrails exceeds the scope of this article, an example of a risk-based guardrail strategy could look as follows:

- Initial Withdrawal Rate: Begin by spending an amount that has an 80% probability of success.

- Upper Guardrail: If the probability of success rises to 100%, increase spending to a level with 20 points higher risk (80% probability of success).

- Lower Guardrail: If the probability of success falls to 25%, decrease spending to a level with 20 points lower risk (45% probability of success).

If your goal in retirement is to make the most of your assets while living so you can enjoy them, a risk-based guardrail dynamic withdrawal strategy will be the right choice for you.

What are your thoughts on a retirement withdrawal strategy? What would be your preferred option? Would you rather spend more retirement money now or leave more of it behind for your heirs and charities?