At The White Coat Investor, we talk about risk and cost frequently—usually in terms of the potential to make money or the possibility of losing it. As the first woman physician commercial astronaut who rode into space last year, I think about risk a little differently.

Achieving my lifelong goal of going to space was worth the 40 years of work it took to get there. I had to decide in advance that the potential cost of losing my life in pursuit of that goal was preferable to the alternative: never taking the chance at all. That decision framework—choosing intentionally rather than avoiding risk by default—has shaped every major inflection point in my career.

Not Letting the Fear of Failure Hold You Back

In my current role as a teacher and mentor to physicians who want to launch and build expert witness businesses, I see clear parallels. Many physicians want to develop new skills, increase financial flexibility, and regain a sense of professional agency. But fear of failure often holds them back. The good news is that clinical training already qualifies physicians to serve as experts. The harder step is deciding to lead and to build something new in the face of uncertainty.

One consistent thread in my work—as an educator and former Space Camp Crew Trainer—is helping people recognize and use skills they didn’t realize they already had. In the United States, our legal system relies on juries of our peers, most of whom have no medical training, to decide the outcome of complex medical malpractice cases. Physicians and other clinicians are uniquely qualified to serve as experts in this system—not as advocates, but as educators.

We already do this work every day in medicine: explaining diagnoses, risks, uncertainty, and outcomes to patients and families. Expert witness work is simply another venue for that same responsibility—to translate complex information clearly, accurately, and ethically.

When I was a Space Camp Crew Trainer in college, I taught high school students—only a few years younger than me—how to launch, fly, and land the space shuttle. I learned those skills by first attending camp myself, studying extensively, and then developing the confidence to teach others. That progression—learning, synthesizing, and teaching under pressure—is second nature to physicians.

It is also one of our most transferable and underappreciated professional skills.

More information here:

How Being an Expert Witness Can Make You a Better Doctor

How to Actually Get Paid as an Expert Witness (or Any Other Side Gig)

The Diversity of the Pathfinders

In studying the evolving traits of Blue Origin astronauts, the most prevalent trait among them is leadership. More recently, there has been a notable shift toward communication, storytelling, philanthropy, and education. These changes reflect a broader evolution in space exploration: from the singular goal of getting to space toward continuing that work for the benefit of Earth.

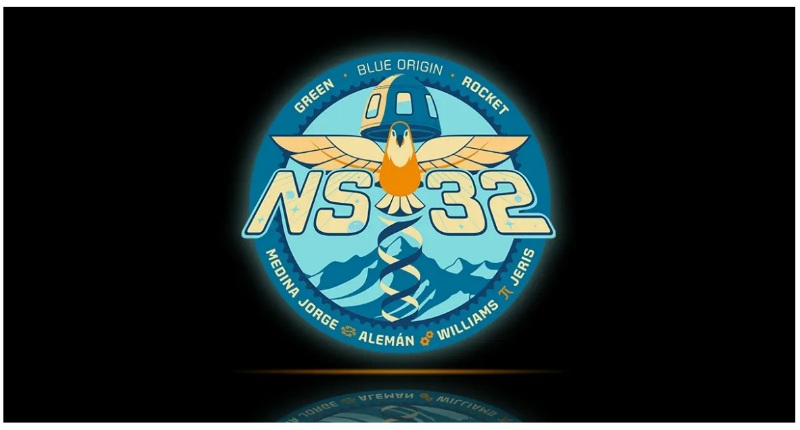

My crew of six called ourselves the Pathfinders because of our diverse paths to space, shown symbolically in our mission patch. The caduceus symbolizes my career as a physician. My crewmates had diverse backgrounds, including IT, education, diplomacy, entrepreneurship, and mountain climbing (to name just a few). Yes, Mark Rocket even has a career in rocketry (and hails from New Zealand, where the Kea bird lives)! Commercial astronaut crews continue to become more diverse in background, profession, and perspective—helping more of humanity see a potential path to space and the shared benefits that follow.

If we focus exclusively on potential loss, we miss the possibility of gain. Going to space, building businesses, and leading organizations has taught me that the larger the goal, the more difficult it is to achieve—but also the more meaningful the impact, both personally and for others.

Some critics derided the all-women NS-31 launch that occurred shortly before my flight, missing a key point. That mission was among the most diverse to date, not because they were all women but because of the breadth of skills, perspectives, and experiences represented. Never before had a crew come together with such range to communicate the meaning of space exploration, conduct research, and show how people from different backgrounds can unite around a shared goal.

More information here:

4 More Times When Doctors Were the Coolest People Ever

Redefining My Medical Career . . . Again

Since my flight in May 2025, I’m frequently asked what it was like to be in space. No, I didn’t see aliens. The landing was scarier than the launch—because if we failed to land safely, the rest of the mission wouldn’t have mattered. I’m also asked how, at age 51 and having achieved my greatest professional dreams, I return to everyday tasks like grocery shopping, checking the mail, or doing laundry.

The answer is that I do them joyfully. I do them knowing that I gave my goals everything I had—not just for my own fulfillment but to demonstrate to others that someone like me, who might look like them, can pursue extraordinary goals, too.

After landing, while being interviewed next to the capsule (you can see it in the video below), I was asked what qualities I possessed as a physician that also made me a good astronaut. My answer was love and compassion. Physicians don’t choose our patients; we care for whoever comes to us. One of the most profound moments of my flight was floating above the Earth and then instinctively turning inward to check on my crewmates—just as I would in a hospital or clinic, leading a team through complex work. That sense of responsibility and connectedness is shared by physicians and astronauts alike.

Expert witness work was one of the tools that allowed me to redefine my medical career and build additional financial flexibility, including real estate investing and the development of educational programs for other clinicians. I wish more physicians viewed expert witness work as a normal extension of medical professionalism—no different from peer review, regulatory service, or quality improvement. At its core, it is an exercise in leadership. Building up a tolerance for risk and enjoying the reward from accomplishing difficult things—tasks I worked on daily in my role as an expert witness building new businesses—were critical steps in my journey to space.

Choosing leadership means choosing action over inaction, despite risk. We often say difficult things aren’t “rocket science,” but consider the complexity and risk involved in building bridges, hospitals, or infrastructure that people rely on daily. Developing tolerance for hard things is what shapes us into the people—and professionals—we want to become.

When the engines of the New Shepard rocket ignite, it takes seven seconds to build enough thrust to lift off. You’re warned in advance that you will see flames and feel vibration—but you are not on fire. That reassurance matters. In space, I experienced three minutes of weightlessness, gazing at the Earth with the knowledge that decades of effort had culminated in that moment. The validation was priceless.

Whether you go to space, we all have a goal that helps us know we are living at our best. It starts with one step.

Have you taken risks in your career to make it a more fulfilling one? Did it work out the way you hoped? Why or why not? Was there something you could have done differently?