By Dr. Jim Dahle, WCI Founder

By Dr. Jim Dahle, WCI FounderI hate writing about negotiation. Every time I do, my spouse, children, employees, partners, and business associates start using all of the suggested techniques ON ME. However, doctors and other high income professionals are often completely naive about the basics of negotiation. Many of them fail to even recognize when they are in a negotiation situation.

The truth is you are probably negotiating with somebody just about every day. With many people and many negotiations, the most important thing is to preserve the relationship. That's why you're so willing to outright lose so many negotiations with your spouse; you gain far more from the overall relationship than you're losing in any given negotiation.

12 Negotiation Techniques You Should Know

Some negotiations are a much bigger deal than others. While reading the rest of this post, we're mostly talking about business relationships, such as a partnership agreement or an employment contract. This post contains just a sampling of common, basic negotiation techniques. Understand how they work and profit.

#1 Know Your Worth and Theirs

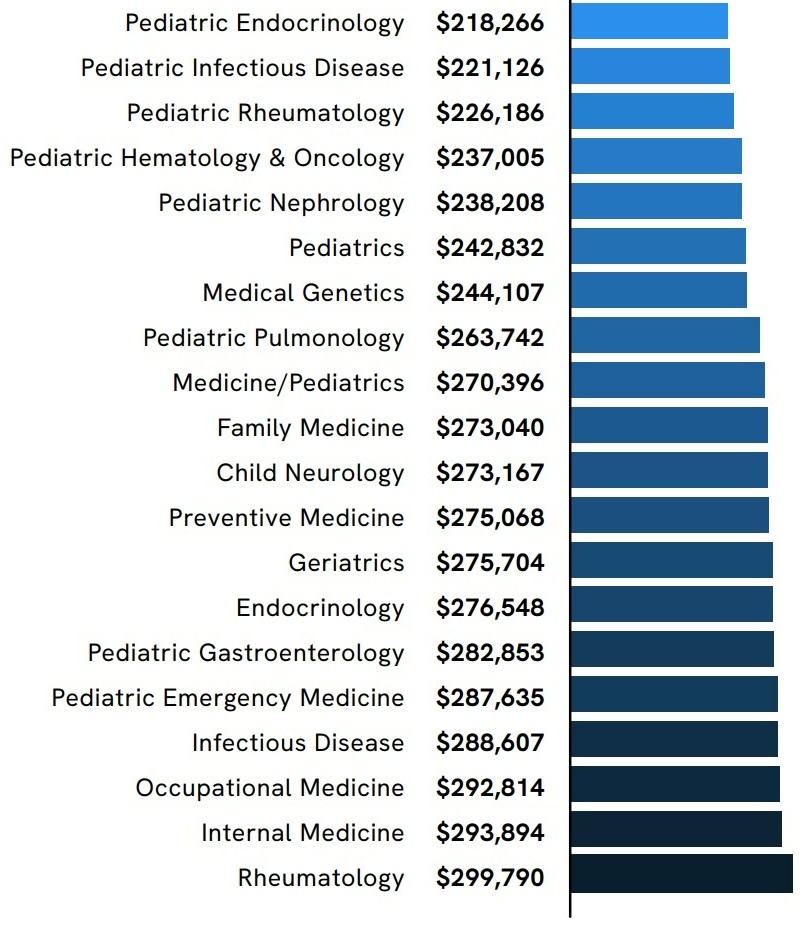

I'm amazed when I meet graduating residents and new attendings who have no idea what the average income in their field is, much less what the 10th, 25th, 75th, and 90th percentiles are. I'm surprised that even an idealistic MS3 would choose a specialty without some idea of how it stacks up income-wise in the field of medicine. At a minimum, pay attention to the salary surveys shared here and on other sites. For example, here's the 2024 Medscape Salary Survey:

Here's some 2023 data from Doximity about the highest- and lowest-paid specialties:

There is more free data out there, but the best and most current data—such as that from MGMA—takes a lot of money to assemble and, thus, costs money to get. It was more than $3,000 to get it the last time I checked, but the cheap way to get the data you care about is to hire a firm that has already purchased it, such as the physician contract review firms we recommend (including Resolve). You can also learn plenty just by talking to colleagues and peers about their incomes. When looking at salary surveys, remember that these figures are often

- Just salaries and may not include profit-sharing and other ownership payments,

- Just averages, half of people are earning more,

- Often months or even years old.

Most doctors also underestimate the range of physician incomes. They don't realize that intraspecialty variation is far wider than interspecialty variation. An older survey showing percentile data for emergency medicine demonstrates this intraspecialty variation well:

As you can see, the 10th percentile for employees at that time was just $213,000, and the 90th percentile for partners was $510,000. That's almost $300,000 in variation, more than the variation in average salaries between pediatrics and cardiology.

In any negotiation, you want to know what you're worth, what your negotiating partner is worth, and how important that relationship is to you.

More information here:

3 Negotiation Tips to Give You the Critical Advantage

How to Negotiate for a Physician Signing Bonus

#2 Know Your BATNA

You are in the strongest negotiation position when you have a solid Best Alternative To a Negotiated Agreement (BATNA). For example, your BATNA might be a job offer down the street that you are perfectly willing to take. “The hospital down the street is offering $550,000 and six weeks of paid vacation. I'd love to stay here, but you need to at least match what they're offering for me.”

That puts you in a far better position than someone who says, “Doximity says the average person in my specialty is making $480,000, and I'm only making $460,000. You should give me a raise.” In that situation, the employer wonders how serious you are about looking for another job. In the first situation, the employer knows you already have and are about to walk out the door if they don't give you a substantial raise. Which is more powerful?

#3 Acquire More Information

Information is power. That's why I hate negotiating with my high-level employees! They know all about us and our business, what we make and how we make it, and often what everyone else in the company is making. Sometimes they've known me for more than four decades! However, in any negotiation, the more you know about . . .

- Your negotiating partner's situation, desires, frustrations, and goals

- Your field in general

- Your productivity

- Your coworkers

- Your own situation

. . . the better off you're going to be. You can get information from all kinds of places, including the partners themselves. They often reveal far more than they intend, and all of that information is gold in a negotiation.

#4 Never Throw Out the First Offer

A standard negotiation technique taught for decades, probably for millennia, is to never throw out the first offer, especially if you don't have a lot of information. Many people are surprised that the first offer is better than they thought they would ever get. When you throw out the first offer ignorantly, you are often leaving a lot of money on the table.

#5 Is That the Best You Can Do?

One of my favorite questions to ask—and it ideally comes right after that first offer—is, “Is that the best you can do?” That often produces a second, better offer before you've even had to make a counteroffer or start negotiating. People often come into negotiations with a low-ball offer, leaving some meat on the bone knowing they'll likely have to give up something later in the negotiation to get an agreement. Asking this question puts them in the position of either lying to you, dodging the question, or shortening the negotiation by telling you what they're really willing to give you. This might also be a good place to end the negotiation with a phrase such as, “I think we're just too far apart.” For example, if their “best offer” is $150,000 and you know you're worth $300,000, you might not want to waste any more time and effort.

More information here:

There Was No Golden Age of Medicine (at Least for Physician Incomes)

Here’s How Much We Make, Save, and Spend as ‘Moderate Earners’

#6 Never Split the Difference

This is another classic negotiating technique. Your negotiating partner may try to take advantage of the fact that splitting the difference feels “fair” by trying to anchor their offer at some ridiculous number. Imagine an employment contract negotiation for a gastroenterologist where the employee offers to work for $450,000. The conniving administrator comes back with $380,000, then begrudgingly offers to split the difference as if they are doing the doc a favor. Well, $415,000 is not a fair deal when you're worth $450,000. Don't split the difference; know what you're worth.

It reminds me of when we bought our current house in 2010. We knew it was going up for sale before it went on the market. We had just looked at all 30 houses for sale in the area. We knew better than anyone else in the world what that house was worth. So, we were surprised to see it listed at $550,000. That number just felt too far apart; we didn't even bother putting in an offer. A few weeks later, the sellers dropped the price to $525,000, and we put in an offer for what it was worth: $475,000. They were insulted! In the end, they sold it to us for $482,000, and even that was probably too much. None of the other 30 houses we had looked at sold in the next six months.

#7 The Pregnant Pause

Most people are uncomfortable with silence. Some are VERY uncomfortable. So, when you provide it with a “pregnant pause,” they will often say all kinds of things that work to your advantage. They may make a concession similar to the “Is that the best you can do?” situation. They may also reveal more information that is useful to you in the negotiation. Be more comfortable with silence, and it will probably work to your benefit.

#8 Point Out Hypocrisy Innocently

I have often been in a negotiation when what is being requested is hypocritical. Standing up and screaming at someone that they are a hypocrite is unlikely to help you achieve your goals. Kill them with kindness. Find a tactful, even innocent, way to point out that their request or offer is hypocritical. For example, imagine you're negotiating a partnership contract that requires you to take 10 days a month of call when all of the other partners are only taking five days. Perhaps you could say, “I want to make sure I understand what you are saying. You want me to cover twice as many calls as anyone else in the practice for the same pay? That can't be right. I must be misunderstanding something.” Then, watch them squirm as they try to justify their hypocrisy or concede the point.

More information here:

#9 Blame Others

While I'm generally a big fan of taking responsibility for your own actions and decisions, blaming others for your inability to offer a better deal to your negotiating partner can be very powerful. Examples include:

- “I would almost be willing to do that because I like you so much, but there is no way my attorney (or accountant, business partner, spouse, etc.) will ever let me sign that agreement.”

- “I wish I could work for that little because I really love your patient population, but I owe it to my husband to make sure to earn enough that I can actually cover our student loan payments and keep a roof over our heads in this expensive city.”

- “Personally, I'd love to help you get those free-standing ED shifts covered, but my partners are never going to agree to what you're proposing. Let's put something together that is more likely to be approved.”

When you need more time to think and acquire additional information, you can always say something like, “I need to run this by my financial advisor; let's schedule another meeting in a few days,” even if your financial advisor is your dog.

#10 Make It Their Problem

Once the issue preventing a negotiated agreement has been identified and outlined, why should it be your responsibility to solve it? Put that in your negotiating partner's lap.

- “I'm sorry you need eight more days a month of call covered; how do you plan to solve that problem?”

- “I definitely need at least $25,000 a month and eight weeks off a year. How do you propose we solve this impasse?”

- “Sounds like you do need another rheumatologist in this practice. How do you plan to meet that need when you can only offer $225,000 a year to prospective hires and they all know the going rate is $289,000 a year?”

It's your job to solve YOUR problems, not theirs. Make the negotiation about their problem, so that you are the solution. Ideally, you'd be the best or even the only solution.

#11 Be Creative

Creativity is dramatically underrated when it comes to negotiations. Too often people get fixated on a viewpoint where everything is black or white. But the world is colored in many shades of gray. It's entirely possible that the employer cannot offer you any more money, but they could possibly decrease call, offer more time off, provide more clinical support, reduce committee responsibilities, boost the 401(k) match, or something else that more than makes it up to you. Many of our business deals have been saved by pivoting the agreement using solutions that neither party had thought of prior to the negotiation.

#12 Seek and Create Win-Win Situations

Some negotiations are truly black and white, where one party wins and one party loses. Every dollar you give up to your negotiating partner (and that's what they are, a partner, not an opponent) is one less dollar you have. However, most negotiations and economic activity take place because it is a win-win for all parties involved. While you can always “win bigger,” a win is a win. If the deal is better than not doing the deal, that's a win. Identify what the other party cares about most, and do your best to give them that. Identify what you care about most, and try to get that. Also identify those items that you and they do not care about all that much. Sacrifice what you don't care about or what doesn't cost you much in order to get something you care about more. Maybe health insurance doesn't matter much to you because your spouse provides it from their job. Give it up in the negotiation to get earlier access to the 401(k) or more paid time off.

Another example from our business here at The White Coat Investor is when we can sweeten a deal for an advertiser by giving them some additional advertising for free. If we haven't sold that ad to someone else, it costs us nothing to throw it into a package. Additional value for them at no cost to us creates a real win-win.

More information here:

Should I Feel Bad About Taking Time Off? Auntie Marge Explains It All

Help, I’m a Doctor in a Cubicle: Auntie Marge Explains It All

#12 ½ Leave Money on the Table

We've covered a lot already, but here's one more bonus tip. It's maybe the most important tip. Most negotiations will be renegotiated at some point in the future. The relationship matters more than getting every dollar out of the deal today. Sometimes it makes sense to lose the negotiation on purpose. Pay the employee too much. Give someone a discount. Get them in the door so they can see what you can do. Create some goodwill and loyalty. Treat people more than fairly, and they'll continue to do business with you for many years and send you all their friends and colleagues. What you lose upfront may come back to you 10-fold later.

Karma is real, and it applies in spades to business.

Looking to increase your income or renegotiate an existing contract? Hop on over to the WCI physician contract review page, where you can find vetted lawyers and compare your contract to other docs.

What do you think? What are your favorite negotiation techniques? Have you used any of the tips listed above?