With the rise of interest rates in the last two years and the continued inversion of the yield curve, interest in cash investments on this website is higher in 2023 and 2024 than it ever has been since the website was founded in 2011. Today's question about cash management comes from a doctor in New York. Keep in mind that even though this specific question is now irrelevant because Schwab has bought TD Ameritrade (and, thus, it no longer exists), the larger point I'll make still remains.

Here's the question:

“I am a high-earning New York City doctor. I invest at TD Ameritrade, which charges a buy/sell fee to use traditional Vanguard mutual funds, including money market funds. We pay about 50% in taxes across federal (37%), state (6.85%), and city (3.876%). Are there ETF versions of Vanguard funds, or what should I use for cash?”

Here's how I answered him in early 2023: There are no ETF money market funds that you want to use. I found a few from places like JP Morgan Chase and Ameriprise with expense ratios ranging from 0.18%-0.99%. One option is to move your investments to Vanguard. That's where we keep our taxable account, Roth IRAs, UTMAs, custodial Roth IRAs, and cash holdings (most of the time). Vanguard has very low costs, fantastic cash and bond options, and more low-cost index funds than anyone else. However, its IT interface and customer service are not always (OK, ever) the best, so lots of people choose to invest elsewhere.

Money Market Funds Are Fixed-Income Investments

To conceptualize money market funds properly, think of them as very, very short-term bonds. While that's not exactly what they are (especially municipal money market funds), they certainly act like it. As Bogle explained, you can get fixed principal or fixed interest but not both. A money market fund provides fixed principal but varying interest. As rates change, the yield on these funds changes, but the most important rule for a money market fund manager is to maintain the Net Asset Value (NAV) at $1.00 per share. “Breaking the buck” is a very, very bad thing in the money market fund world.

More information here:

Why Are Municipal Money Market Fund Yields So Volatile?

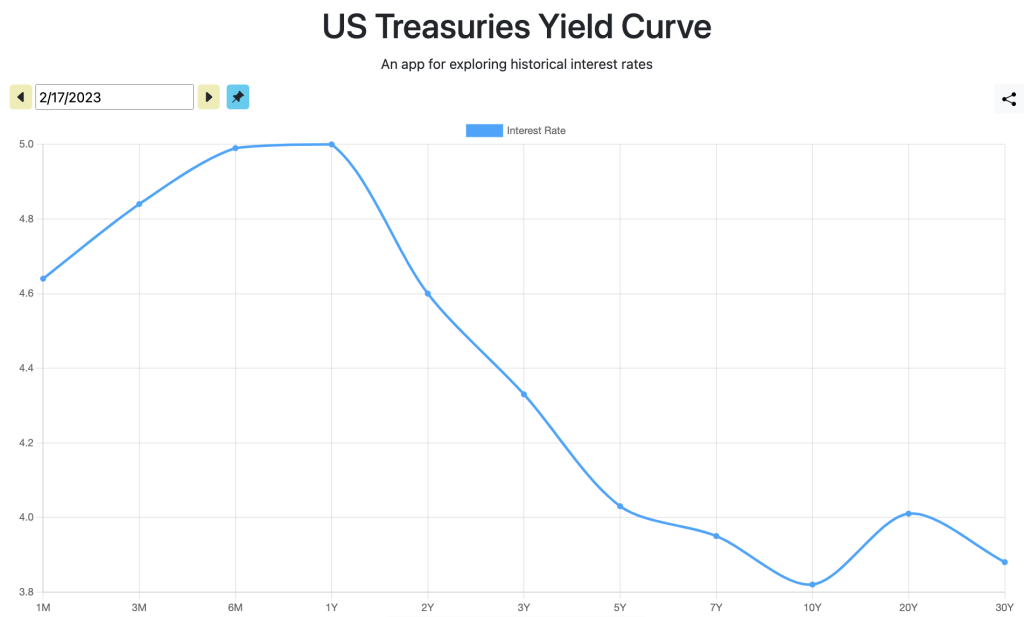

Inverted Yield Curve

The “yield curve” is currently “inverted.” That means that longer-term bonds have lower yields than shorter-term bonds. This is an unusual situation, but it does happen occasionally. Some people believe it is a sign of a coming recession. However, the data shows that inverted yield curves have predicted something like 42 of the last 27 recessions. In other words, sometimes it is a sign of a coming recession, and sometimes it isn't. What it really means is that the markets (i.e. the sum of all the people buying and selling fixed income) believe that interest rates in the future will be lower than they are right now.

This is what the Treasury yield curve looked like in February 2023 when the New York City doctor emailed:

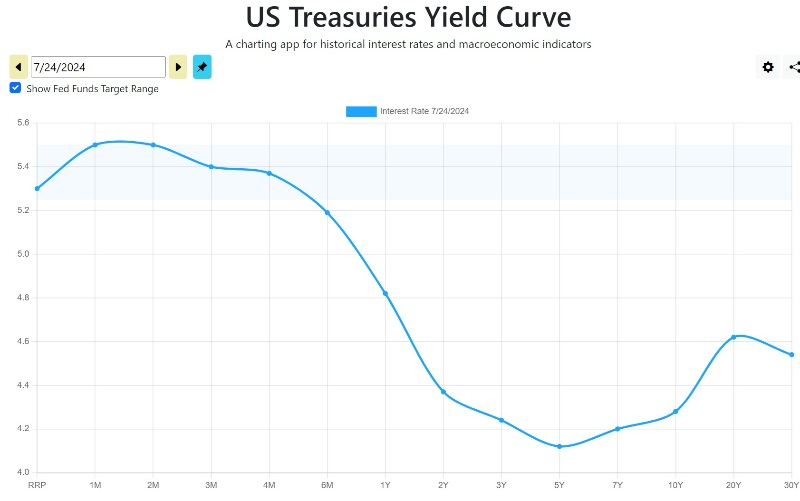

And as of July 2024, the Treasury yield curve looked like this:

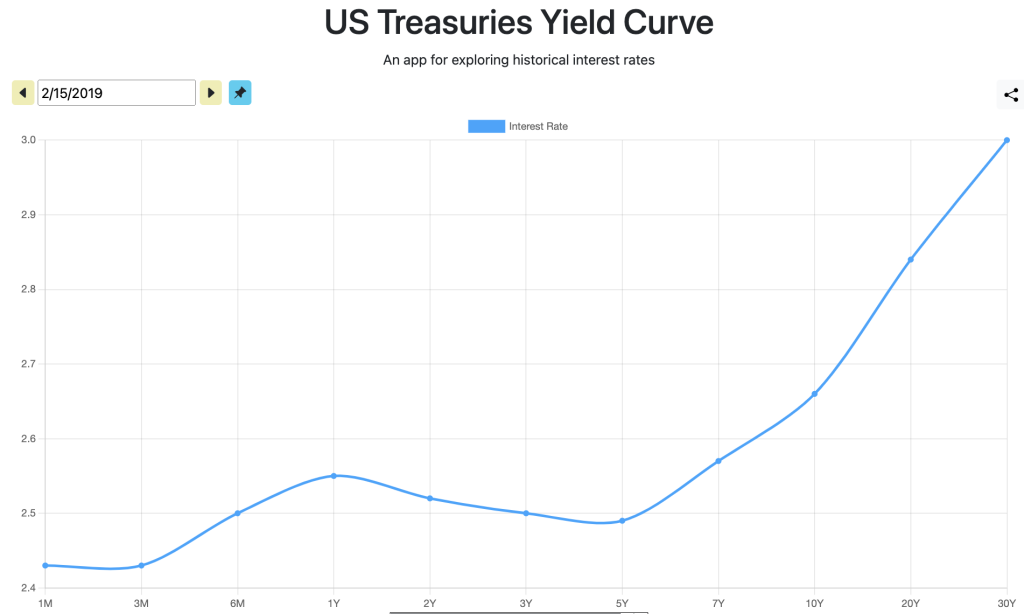

As you can see, the highest yield on the newest chart is at 1 month and 2 months. A 5-year Treasury only pays 4.1%. A 1-year Treasury has a yield of 4.6%. And 1- and 2-month Treasuries yield 5.5%. Thus, the market predicts that at some point between one year and five years from now, the interest rates on cash will be lower. I find this interesting given that it was predicted that the Fed would cut interest rates a few times in 2024 but that it still hasn't happened. But this is what the market believes. A more normal yield curve looks like this one from 2019:

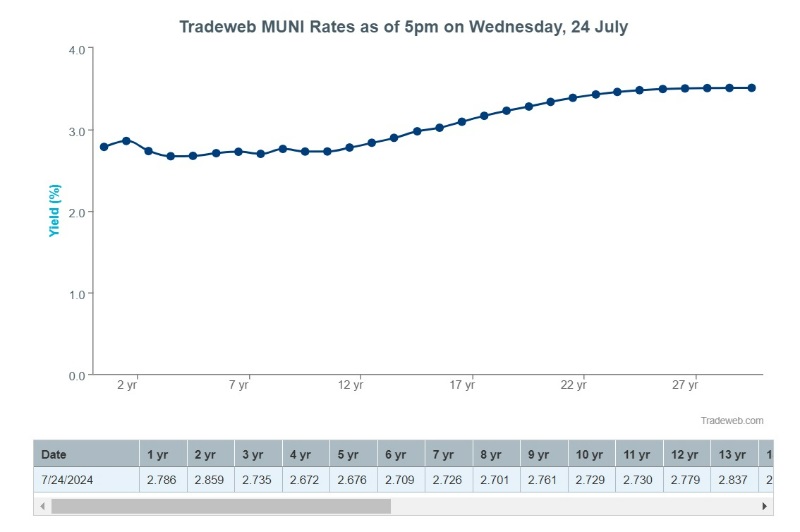

There are other yield curves for real (after-inflation) yield curves (the one used with TIPS) and municipal bond yield curves. Here's the muni yield curve:

Note that just because the Treasury yield curve is inverted does not mean the municipal yield curve is inverted. At any rate, lots of people ask, “Why would I invest in bonds when I can make more in cash?” When you invest in very short-term bonds (i.e., cash such as a money market fund or a high yield savings account), you are basically saying that you believe that rates are going to either stay the same or go up. If you believed rates were going to fall, you would “lock in” those yields by buying bonds (or CDs). Locking in rates means that you will keep the same rate until the security matures with individual bonds or you will get a nice capital gain with a bond fund as the securities are now sold for more than you paid for them.

People have been excited about buying “Treasury bills” with their cash at TreasuryDirect. While you can do this, you can also just invest in money market funds that do the exact same thing. You're basically just running your own money market fund. Whether that is worth the savings (of the expense ratio of the fund) to you depends on how you value your time. Treasury bills are very liquid but perhaps not quite as liquid as a money market fund (although some might argue they're even more liquid in serious economic turmoil). At any rate, you can buy 1-month Treasury bills today with a yield of 5.5% but the Vanguard Treasury Money Market Fund is only yielding 5.29%. So, you can earn 0.21% more if you're willing to run your own money market fund. I will gladly pay 0.21% to someone else to do that for me.

Vanguard vs. Schwab Money Market Funds

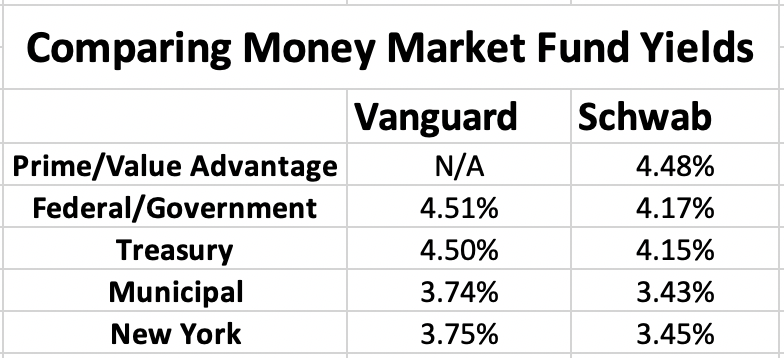

Interestingly, I find Vanguard to be the best at running fixed-income mutual funds. Its volume, attention to detail, and mutual/at-cost structure give Vanguard a pretty clear edge in my book. I wasn't surprised when I compared their money market funds to competitors, such as Schwab. Here are some relevant comparisons at about the time the doctor from New York wrote to me several months ago. Though the yields today are a little different, Vanguard's yields are still higher than Schwab's. And the point I'm making still stands.

As you can see, the Vanguard funds are just better in every category. This is one of the costs of investing elsewhere. Vanguard doesn't even have a prime money market fund anymore, but its treasury yield is so high it's better than Schwab's prime fund even before taxes are applied.

More information here:

The Benefits of High Rates on Cash

Doing the Calculations

Now for the fun part: math! Remember that you can't just do these calculations once. I'm trying to teach you to fish, not give you a fish. While you're pretty safe with the takeaway that “Vanguard money market funds are better than Schwab money market funds,” you are not safe with a takeaway like, “I should use the New York Municipal Money Market Fund.” While that might be the right answer for you today, it may not be next week, next month, or next year. If you want the best yield, you have to be doing these calculations regularly. It is particularly worthwhile doing them around the months of January and July (when municipal money market yields tend to be abnormally low) and in April (when municipal money market yields tend to be abnormally high).

Your goal is to compare yields on an after-tax basis. Let's look at all five of these Schwab money market funds and calculate the after-tax yield for this particular investor when he originally asked his question. Remember, his federal tax bracket is 37%, his state tax bracket is 6.85%, and his city tax bracket is 3.876%. The Treasury funds are state and city tax-free. The federal/government funds are partially state and city tax-free. Without doing a lot of adding, I couldn't figure out what percentage of the fund was Treasuries, so we'll assume 50%. It probably varies over time anyway.

The municipal funds are federal tax-free. The New York municipal funds are federal, state, and possibly even local tax-free. I looked through all the documents I could find, and I could not figure out what percentage of the income from the New York-specific fund is New York City tax-free, so in this calculation, I'm assuming it all is. If you can figure out that percentage, let us know. I'll bet it can be found on the 1099 of an investor in that fund.

Value Advantage

After-tax yield = 4.48% * (1-37%-6.85%-3.876%) = 2.34%

Government

After-tax yield = 4.17% * (1-37%-6.85%*50% – 3.876%*50%) = 2.40%

Treasury

After-tax yield = 4.15% * (1-37%) = 2.61%

Municipal

After-tax yield = 3.43% * (1-6.85% – 3.876%) = 3.06%

New York Municipal

After-tax yield = 3.45%

For this investor in this moment, the highest after-tax yield can be found in the New York-specific municipal money market fund.

What do you think? How often do you do this calculation for your cash? Do you use a state-specific municipal money market fund? Why or why not?