President Trump has instituted a $100,000 fee for H-1B visas. The explanation for this fee in the Sept. 19, 2025, presidential proclamation was to prioritize the hiring of American workers instead of foreigners. Basically, that foreigner had better be at least $100,000 better than a comparable American, or companies will hire the American. Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick called the H-1B visa program the “most abused visa” and further explained that this fee was intended to stop tech companies from exploiting the program. The fee is supposed to stop companies from “spamming the system” and driving down wages.

Like many announcements by the Trump administration, this one came suddenly and caused lots of chaos on a weekend (the weekend I wrote this) as people scrambled to understand what was happening. Then, it was almost immediately changed/clarified after the initial announcement. The $100,000 payment was initially understood to be an annual fee, but it is not; it's a one-time fee. It also only applies to NEW visa holders, not those already here on a visa.

We don't comment on every economic action taken by the administration, but this is an issue worth discussing here at WCI. Lots of doctors train in the US on H-1B visas, and some attendings remain on them for quite some time. How will this fee affect future foreign doctors?

How Visas Work

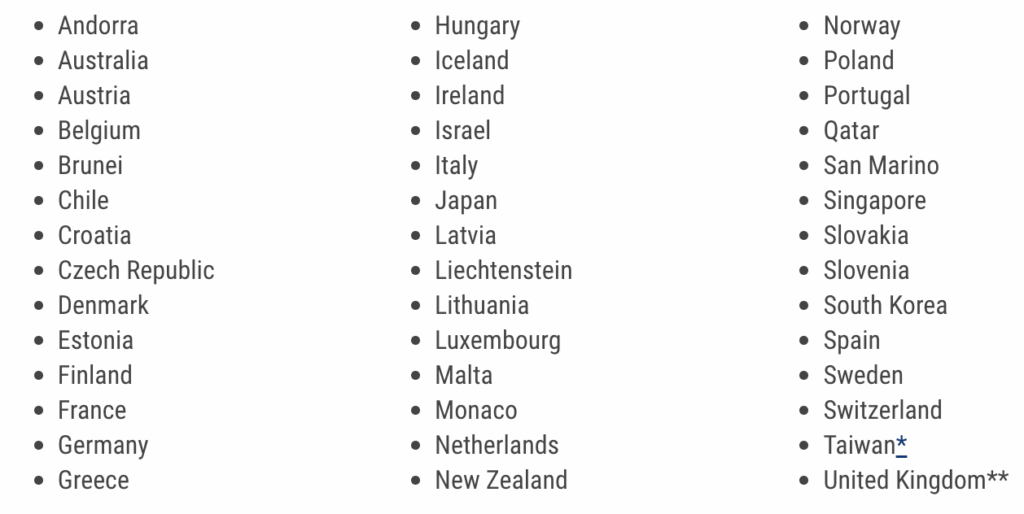

Before we get into the doctor-specific issues, we probably need a broader discussion about visas. I didn't know much about them prior to writing this post, and most WCIers probably don't either. A visa is a pass to enter a country, such as the United States. People from countries that participate in the Visa Waiver Program (42 countries, mostly European) do not have to get a visa for short tourist or business stays. Here are the countries in the program:

If you're from another country not on that list, you have to get a visa. Even if you're from a VWP country, if you've traveled to Iran, Iraq, Libya, Cuba, North Korea, Somalia, Sudan, or Yemen, you'll also need to get a visa even for a short visit. A visa doesn't guarantee entry. It is a required but not sufficient condition. An immigration officer can still deny you entry. A visa is not a passport either. You always need a passport, but you only sometimes need a visa.

There are more than 180 different types of visas, broadly divided into immigrant visas and non-immigrant visas. Non-immigrant visas need a purpose, such as tourism, work, study, or medical treatment. For our purposes today, we're mostly talking about non-immigrant visas to study and work. Foreigners may study in US medical schools (thus becoming AMGs) just like Americans can study in foreign medical schools (thus becoming IMGs). A foreigner, whether an IMG or AMG, will commonly apply to match into a US residency or fellowship. Since doctors generally get paid better in the US than wherever they came from and since they like it here or have relationships here, they often try to stay permanently after completing their training.

The letter in the name of a visa has a meaning.

- B — Tourist

- F and M — Student

- H and L — Temporary work

- J — Temporary education or cultural exchange

- E — Treaty traders or investors

- O — Athletes and entertainers

- C — Transit through the US

- I — Journalists

There are also various types of visas within each category. For example, here are some H visa categories:

- H-1B — For workers in “specialty occupations” that require a high level of education or specialized skills.

- H-2A — For temporary or seasonal agricultural work.

- H-2B — For temporary or seasonal non-agricultural work.

Typically, foreigners in US medical schools are on an F-1 visa. Residents and fellows can be on an H-1B visa, although I believe most are now on a J-1 visa. Approximately 3% of US medical students are foreigners, but since they're usually on F-1 visas, this new fee does not apply to them. Approximately 6,600 (18%) non-residents matched into residency in 2025. That's a MUCH higher percentage than 3%, and the percentage tends to be highest in primary care residencies. Thirty-nine percent of internal medicine residents are IMGs (although obviously not all of those are non-residents). I couldn't find the exact number of residents and fellows currently on an H-1B visa, but I would love to add it to this post if you have a reliable source.

What Is the Difference Between H-1B and J-1 Visas?

H-1B visas require employer sponsorship, and they are for temporary, specialized workers. But they can be a direct path to a green card (permanent residency). There are annual limitations and caps on H-1B visas unless the employer qualifies for an exemption. Basically, H-1B visas offer more flexibility to stay in the country and work after residency. The Department of Labor oversees H-1B visas.

Downsides of an H-1B visa include:

- Visa is tied to a specific employer, leading to potential job loss or fear of retaliation for complaining

- May also lead to lower wages in some jobs due to a lack of other options (no good BATNA)

- Annual lottery system makes it harder to get the visa in the first place (although I am now told that the lottery doesn't apply to docs)

- Six-year maximum duration

- New one-time visa fee ($100,000)

- Employer costs are higher to run the program, both financially and in time and hassle

- Employers are required to pay the “prevailing wage” (probably an upside for the foreigner)

J-1 visas are often sponsored by organizations like the Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG). They are for educational and cultural exchange, with the expectation that the physician will return to their home country. They require a two-year home residency requirement after completion of the program, or a waiver, to stay in the US longer. More residency programs accept J-1 visas for initial training, and more foreign residents are on J-1s than H-1Bs. You cannot apply for permanent residency while on a J-1, though—that's called “dual intent.” The ECFMG and sponsors oversee J-1 visas.

Downsides of a J-1 visa include:

- Two-year home residency requirement before applying for citizenship

- Strict adherence to approved program (i.e., no moonlighting)

- Poor sponsor oversight leading to poor working conditions, lack of promised training or cultural experience

- Must have health insurance, pay taxes, and avoid welfare

- Some categories have a five-year limit (docs typically get up to seven)

- 24-month ban on repeat participation

- No clinical appointments

- One-time SEVIS fee ($220)

There was a movement a few years ago toward more residents being on H-1Bs than on J-1s, but that pendulum has swung back in the last few years.

More information here:

Landing a Physician Job in the US While on a J-1 Visa

IMG Financial Survival Guide to Residency in the US

What Is This ‘H-1B Spamming' That the Administration Doesn't Like?

H-1B spamming is fraud, gaming the H-1B lottery system. It's when multiple companies (which may all have the same owner) submit numerous lottery registrations for the same foreign worker to increase that worker's odds of selection. It is apparently frequently used by tech staffing and consulting companies. Starting in 2023, multiple applications for the same worker became more common than single applications, so it really is a problem. Presumably, the fee will stop this, although it is likely to have other effects as well.

How Is the New Fee Going to Affect Doctors?

Now that we have some background information, we can speculate about how this is going to affect doctors. First, it's not going to affect residents on a J-1 at all. It's also not going to affect doctors who already have an H-1B visa. We're really talking only about future residents. I suspect the main effect here is that the pendulum between H-1B and J-1 will swing even further toward the J-1 side and that there will be few H-1 B residents at all in a few years. It's just going to be easier for hospitals to do J-1s rather than fork out $100,000 a resident to hire those on H-1B visas.

The downside of training on a J-1, of course, is that you're probably not staying here after training. So, the overall effect is that we will have fewer foreign doctors, and, thus, fewer doctors overall. Our residency programs will be training doctors who are not going to work in the US, at least for a couple of years after training. Certainly, we'll have fewer primary care doctors. It will probably be a little easier for US doctors to match into residency and to find jobs afterward, particularly in primary care. With fewer primary care doctors, those docs may make more money, but access to them will be more limited.

More information here:

How the ‘One Big Beautiful Bill’ Act Will Affect Doctors

Trump Will Allow You to Make Dangerous Moves in Your 401(k), Including Adding Crypto

Trump Accounts — What to Know About This ‘Baby Bonus’ from the One Big Beautiful Bill

What Should I Do If I Am on an H-1B?

Nothing. This fee doesn't apply to you.

What Should I Do If I Want to Get an H-1B to Train in the US?

Wait a few months and let this all get sorted out. We'll need to see if hospitals and residency programs are still willing to pay this fee for you to fill their program. If you have wealth, you could possibly pay for part or all of this fee yourself (although I'm told this is not allowed), making you more attractive to a residency program. Perhaps H-1B fee loan programs will pop up to help, as well. Maybe that isn't the end of the world since many FMGs don't have any student loans.

Is Something in This Post Wrong?

Almost surely. We'll fix it as soon as you point it out or the rules change again. We know many WCIers are on these visas and hope you will help us all to understand this issue better by submitting comments below.

What do you think of this new policy? What are the likely effects to be? What do you think will happen to the medical profession if H-1B workers (or their employers) have to pay this fee?