One of the biggest financial dilemmas for retirees is Sequence of Returns Risk (SORR). This is generally thought of as a retirement where, despite having adequate average returns during the period, the lousy returns show up first, and the lethal combination of withdrawals and dropping portfolio values early in the retirement decimates the portfolio and causes the retiree to run out of money before running out of time.

The focus seems to always be on the bad returns. However, when you dive into the data, the bad returns really haven't been the problem in the past.

The 4% ‘Rule'

Consider the 4% guideline, even though pretty much nobody actually uses that as their retirement withdrawal method. The idea is that in your first year of retirement, you pull out 4% of the portfolio value. Then, in the second year, you pull out 4% of the original portfolio plus an adjustment for inflation, no matter what the portfolio performance has looked like over the last year.

You continue to do this throughout your theoretical 30-year retirement. It's not 4% of the current portfolio value. It's not 4% of the original portfolio value, at least after the first year. It's 4% of the original value plus inflation. It turns out that the inflation matters quite a bit. More than the returns, actually.

Investment Returns in the 1970s

Consider the poster boy for SORR. Of the historical data, there is no 30-year period worse for retirees than retiring in 1966. What happened to the portfolio of retirees who retired in 1966? Let's take a look.

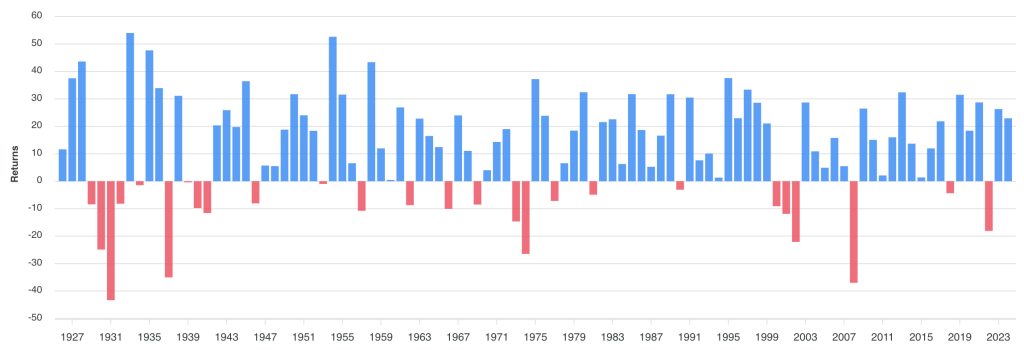

First, let's view all the historical data for the S&P 500 or its equivalent.

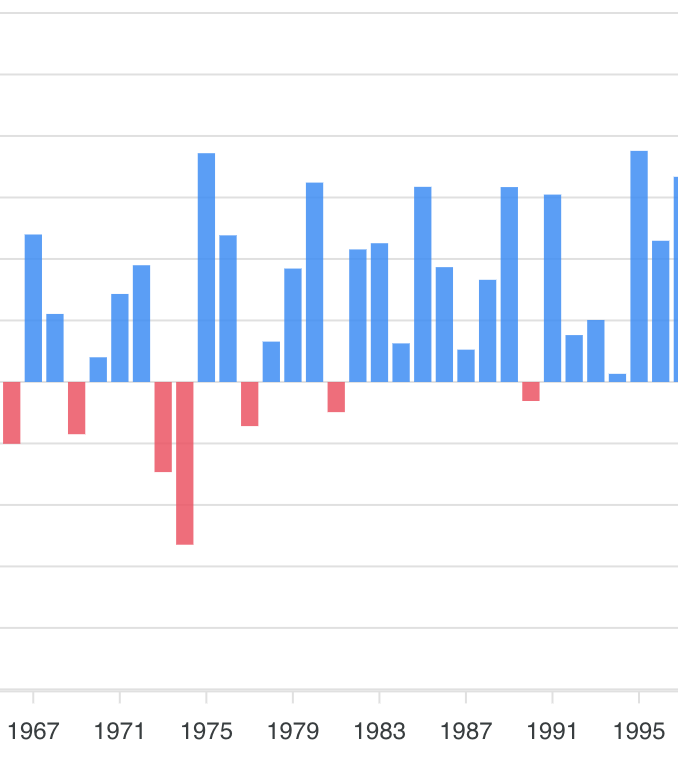

Blue is good and red is bad. Lots of red during the Great Depression, a little red in the '70s, a nasty dot.com crash in the 2000s, and 2008 and 2022 don't look so good either. Now, let's look at our poster boy carefully.

There are certainly some bad years early on in the retirement (four of the first nine years have significant losses). But the gains around those years seem to more than make up for them. Here is what they look like in numerical format:

- 1966: -9.97%

- 1967: 23.80%

- 1968: 10.81%

- 1969: -8.24%

- 1970: 3.56%

- 1971: 14.22%

- 1972: 18.76%

- 1973: -14.31%

- 1974: -25.90%

- 1975: 37.00%

Yes, a few bad years and only one really terrible year, but there were plenty of good years, too. The problem with the 1966 period IS NOT the investment returns. They weren't awesome, but they weren't that bad. If I annualize that 10-year period from 1966-1975, I get an annualized return of 3.3%, significantly better than 2000-2010. At least on a nominal basis.

More information here:

How Flexible Might You Have to Be in Retirement?

Retirement Income Strategies — And Here’s Our Plan for When We FIRE

Inflation in the 1970s

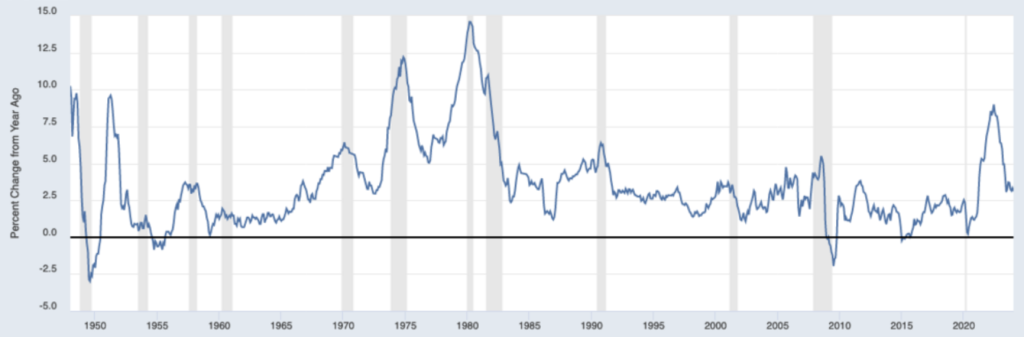

The problem, as those who lived through the 1970s know, was inflation. It's referred to now as stagflation, due to stagnation of the economy combined with inflationary pressures in the 1970s. Let's look at the inflation rate now. Here's a historical chart of the CPI-U inflation rate:

See those big spikes in the middle? Let's blow up the chart a bit.

Here are the inflation numbers for that 10-year period starting in 1966.

- 1966: 2.9%

- 1967: 3.1%

- 1968: 4.2%

- 1969: 5.5%

- 1970: 5.7%

- 1971: 4.4%

- 1972: 3.2%

- 1973: 6.2%

- 1974: 11.0%

- 1975: 9.1%

And no, it didn't all get better when I entered the world in 1975. Check out the next few years:

- 1976: 5.8%

- 1977: 6.5%

- 1978: 7.6%

- 1979: 11.3%

- 1980: 13.5%

- 1981: 10.3%

- 1982: 6.2%

Now, we all lived through a little inflation recently. Look at the chart above or the data below:

- 2020: 1.2%

- 2021: 4.7%

- 2022: 8.0%

- 2023: 4.1%

- 2024: 2.9%

Basically, we had three years of higher-than-desired inflation, one of which was moderately high. Our 17-year poster boy period had 17 years of higher-than-desired inflation, eight of which were moderately high and four of which were extremely high. This was serious inflation over a very long period of time. You know how your groceries feel really expensive now? Imagine how that felt in 1982.

The big problem with retiring in 1966 was not the investment returns. The problem was the real return, i.e., the inflation-adjusted return. The returns just were not keeping up with inflation. That means the portfolio is dropping rapidly in inflation-adjusted value AND you're withdrawing significantly more from it every year. That's a recipe for portfolio disaster. Want to know why the 4% rule is the 4% rule and not the 5% or 6% rule? A big part of the reason why is 1966-1982.

Interestingly, a retiree in 1973 would have been even more whacked by inflation early in their retirement. Why, then, isn't 1973 the poster boy case? It's because the historically long bull market beginning in 1982 came soon enough to bail them out. The 1966 retiree had to go through almost all the same high inflation as the 1973 retiree, but they had to wait seven more years for that bull market to begin.

The Inflation Pendulum Doesn't Swing

There's another reason why inflation is so much worse than just poor returns when it comes to SORR. When good investments have a period of poor returns—whether they're stocks, bonds, or real estate—the following period tends to have better-than-average returns. The pendulum swings. There is a return to the mean. For example, bonds do poorly when rates rise. Now that rates are higher, bonds do better and might do a lot better if rates fall. Same thing if stocks or real estate drop in value. Valuations like the P/E ratio or cap rate all get better. You're now paying less for a dollar of earnings.

However, that doesn't happen with inflation. When the economy (if the economy) recovers from severe inflation, the inflation rate returns to normal, not deflation. There's no pendulum effect. There is no return to the mean. That value is just gone, forever.

More information here:

Why You Must Adjust for Inflation in Long-Term Planning

You Can’t Hedge Against Inflation in the Short Term

What Can Retirees Do?

I've always said inflation is the investor's greatest enemy. That is even more true in retirement when your main source of income becomes your portfolio rather than a job that comes with periodic raises for inflation. Your portfolio, even in retirement, must be specifically designed to withstand long-term inflation. Your entire retirement spending plan must be designed to withstand it. A few methods can do so, but they all have downsides.

#1 Use a Really Low Withdrawal Rate

This one works fine for those who are particularly wealthy with regard to their desired spending. If you retire with $5 million and only spend $100,000 a year (2%), you're going to ride out a nasty period of inflation early in retirement just fine. The downside is that nasty periods of inflation don't show up most of the time, so if you would actually prefer to spend more money than 2% of your portfolio, this is a lousy plan most of the time.

#2 Use an Aggressive Asset Allocation

Those who have spent a lot of time staring at the Trinity Study and its tables have probably internalized this lesson. Let's stare at it again for a second for those who have not.

Let's consider the 5% column, just because it's more interesting than the 4% column. If you have a portfolio of 100% bonds, you would have run out of money in less than 30 years 78% of the time in the past. But if you increased that asset allocation to 50% stocks, you would have run out of money only 33% of the time. At 75% stocks, only 18% of the time. Why is that? Inflation is the main reason. In the long run, stocks generally have higher returns than bonds, so there is more growth that can be used to overcome the effects of inflation, despite the increased volatility of the returns.

Bottom line: You still need some risky but higher-returning assets in your portfolio as a retiree, whether those are stocks, real estate, or something else. It can't all be bonds and CDs and cash.

#3 Index the Bonds to Inflation

One thing that did not exist in 1970 but does today is inflation-indexed bonds. In the US, these are only available from the government and are only indexed to the CPI, and they take the form of Type I Savings Bonds (I Bonds) and Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS). Remember that the issue is inflation, not poor returns. Guess which kind of bond does better with unexpected inflation in the long run: TIPS or nominal bonds? Yes, you can still get whacked when interest rates go up (at least real interest rates), but nominal bonds were absolutely crushed in the 1970s. TIPS would have, at least theoretically, been dramatically better.

So, the strategy is to put a significant chunk of your bond money into TIPS. Some “Liability Matching Portfolio” (LMP) advocates would even have you build a 30-year ladder of TIPS that match your annual required spending.

#4 Delay Social Security to 70

One method people have for dealing with SORR is to buy Single Premium Immediate Annuities (SPIAs) that put a floor under your spending. The problem with a SPIA is that you can no longer buy one that is indexed to inflation. While a SPIA bought in 1966 would still be paying you something 20 or 30 years later, that money would not have gone very far.

You know what IS indexed to inflation, though? Social Security payments. But how can you get more of those? By delaying when you start them. Even better, the Social Security Administration honestly offers a better deal on this than insurance companies do. Social Security experts are all in agreement on this point, but 27% of American retirees still take Social Security at 62 and 90% take it before 70. Some pensions, particularly government pensions, work the same way, so be very careful before cashing out a pension that can be indexed to inflation.

Do what everyone else does, and you'll get what everyone else gets. And if 1970s-style inflation shows up again early in your retirement, you're not going to like it.

#5 Leverage

I'm not a huge fan of debt, especially in retirement, but fixed-rate, low-interest-rate debt is a heck of an inflation hedge. This is often combined with a real estate portfolio. Let's say you own a few reasonably leveraged investment properties—either directly or passively—and inflation hits hard. What happens? The rents collected go up, the value of the property goes up, and that low, fixed-rate debt becomes easier and easier to pay back every year. Not a bad reason to include a bit of reasonably leveraged real estate in your retirement portfolio.

#6 Speculate

Long-term readers know I'm not a huge fan of speculative investments, but this is a method some have employed in an attempt to weather inflation-related SORR. I can still remember seeing a small plastic bucket of silver coins hidden in my closet as a preschooler in the late 1970s. (No, it's no longer there. Don't go breaking into my parents' house, please.) That was apparently pretty common back then. Today, people may own precious metals, commodities, cryptoassets, or empty land as some sort of inflation hedge. I think the downsides of these outweigh the upsides, but if you disagree, at least limit the amount of speculative assets in your portfolio to a single-digit percentage.

When you think about SORR in the future, please don't just think about poor investment returns. Also, think about inflation. Inflation is the far bigger killer of retiree portfolios.

What do you think? Do you agree that inflation is more dangerous than bad returns? What are you doing or planning to do about inflation-related SORR in retirement?