By Dr. Jim Dahle, WCI Founder

By Dr. Jim Dahle, WCI FounderPart of financial literacy is understanding how the tax code works. Unfortunately, that is a major undertaking. Today, we are going to look at a tiny part of the tax code and discuss why it matters to white coat investors. The text for our sermon can be found in an obscure worksheet in the Form 1040 Instructions, specifically the Qualified Dividends and Capital Gains Tax Worksheet — Line 16. This isn't even a form you submit to the IRS. If you pay someone else to prepare your taxes or if you prepare your own taxes using software, you may have never seen this worksheet.

Nevertheless, it is important to understand how it works and what it means.

What Are Qualified Dividends?

Before we get into the worksheet, we should do a few definitions. Investors are often paid dividends by their investments. Dividends are generally taxed at your ordinary income tax rates. However, some dividends are special. They are qualified with the IRS for a special, lower tax rate. The qualified dividend tax brackets are 0%, 15%, and 20%—much lower than the ordinary income tax rates ranging from 10%-37%. Note that most states do NOT offer a lower tax rate on qualified dividends.

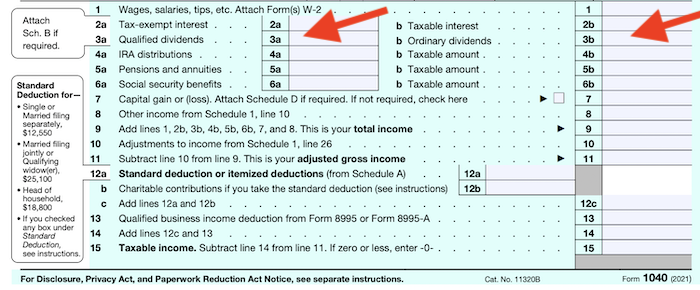

A qualified dividend is paid by a C Corporation whose shares you owned for at least 60 days, although that 60 days can be split in any way around the ex-dividend date. If you bought it five days before the ex-dividend date and sold it 12 days afterward, that dividend is NOT a qualified dividend, and you will pay at ordinary income tax rates on it. (It's something to be careful about when tax-loss harvesting). Qualified dividends show up on line 3a of Form 1040. Note that the ordinary dividends line (3b) includes unqualified and qualified dividends.

What Are Capital Gains?

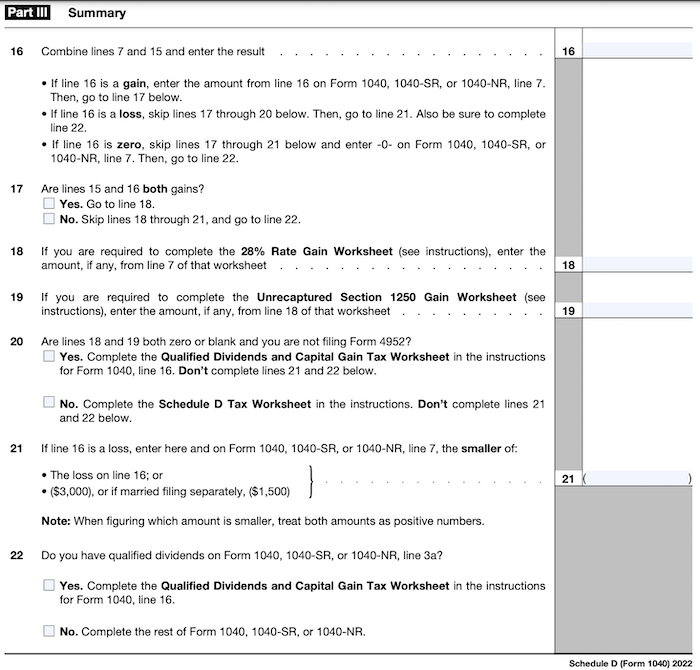

Capital gains and losses occur when you sell an investment. If you sold it for more than you paid for it, then you have a capital gain in the amount that the price you sold for exceeds the amount you paid (the basis). If you sold it for less, you have a loss. If you owned it for 366 days or more, that is a long-term capital gain or loss. If you owned it for 365 days or less, that is a short-term capital gain or loss. Long- and short-term capital gains and losses are totaled up on Schedule D. First, short-term capital gains and losses are zeroed out against each other (line 7), and then long-term capital gains and losses are zeroed out against each other (line 15). Then, the magic happens in Part III of Schedule D.

First, in line 16, you sum the long-term and short-term numbers together. If it is a gain, you enter that gain on line 7 of Form 1040 that we saw above and go to the next line. If it is a loss, you skip the next few lines and go to line 21.

When You Have a Gain

In line 17, you have to look at whether you have a long-term gain AND a total (long-term plus short-term) gain. If you do, look and see if you have a gain on collectibles (gold, Beanie Babies, etc.). You have to pay 28% on those. You also look to see if you have an unrecaptured Section 1250 gain. This is the depreciation recapture tax when you sell a real estate investment that you have been depreciating. This is taxed at a maximum of 25%. If you don't have either of those, go on to the Qualified Dividends and Capital Gains Tax Worksheet (the subject of this blog post.) If you have those, you go to a different worksheet found in the Schedule D Instructions. It's quite a complicated two-page form. Think of it as the complicated version of the Qualified Dividends and Capital Gains Tax Worksheet for those dumb enough to invest in Beanie Babies. Just kidding. It's no big deal to complete, just a few extra lines (although if you're doing it by hand, you're a glutton for punishment). Why these two forms that do the same thing are in completely separate IRS instructions is beyond me.

If you have a total gain but a long-term loss, you are now on line 22. It asks about qualified dividends. If you have those, you'll need to fill out the Qualified Dividends and Capital Gains Tax Worksheet next. Otherwise, you're done with Schedule D, and you'll be paying ordinary income taxes on everything on line 7 because those are short-term gains. Note that your long-term losses did offset your short-term gains.

When You Have a Loss

When you have a total loss, you go to line 21. You put that loss or $3,000, whichever is smaller, on Line 7 of your 1040. This is the $3,000 capital loss deduction that you can use against your ordinary income each year with the rest carried forward. Then, go to line 22. If you have dividends, you have to go on to the Qualified Dividends and Capital Gains. If you do not, you're done with Schedule D.

More information here:

13 Ways to Lower the Tax Bill on Your Income

The Qualified Dividends and Capital Gain Tax Worksheet

Now we move into the relatively detailed Qualified Dividends and Capital Gain Tax Worksheet. If you don't want to work through this with me, that's fine. Just skip it. Down below, I'll illustrate the lessons one can learn by working through it.

The worksheet begins with your taxable income on the first line. On lines 2-5, you essentially subtract your capital gains and dividends from the taxable income.

Lines 6-21 seem ridiculously complicated. Just follow the instructions carefully, and it's no big deal. What you are doing on these lines is simply calculating the tax due on your qualified dividends and long-term capital gains. Line 9 tells you the amount in the 0% qualified dividend/LTCG bracket, line 18 tells you the amount in the 15% qualified dividend/LTCG bracket, and line 21 tells you the amount in the 20% qualified dividend/LTCG bracket.

Now, you calculate the tax due on your income that is not qualified dividends/LTCGs on line 22.

On line 23, you add all of that tax together. You make sure it isn't less than you would pay if you didn't have any qualified dividends or LTCGs on line 24. I can't imagine that happens very often. I'm sure there's a scenario where it does (or this line wouldn't be here), but I can't think of it. Line 23 should almost always be less than line 24, so that's what goes on line 25. That is transferred to Form 1040 Line 16 as your “Tax.” You add some more taxes to it (like self-employment tax, Obamacare taxes, and household employee taxes from Schedule 2) on 1040 lines 17 and 18, and then you add in your credits and payments to find out how much total tax you owe. Compare that to what you paid and settle up with the IRS to be done with your federal income taxes.

More information here:

Tax Policies: Enjoy Them but Also Reform the Right Ones

Lessons Learned from the Qualified Dividends and Capital Gains Tax Worksheet

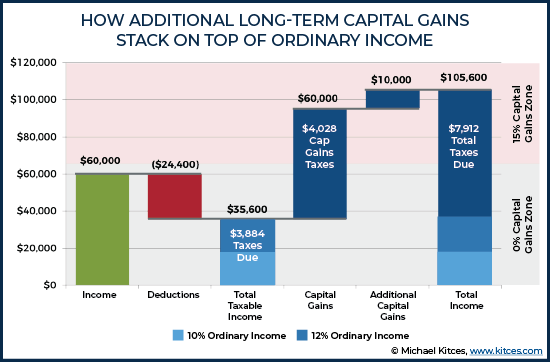

The most important lesson to learn from this worksheet is that qualified dividends and capital gains stack on top. What does that mean?

The first thing it means is that doubling or tripling your qualified dividends and capital gains does not push you into a higher ordinary income tax bracket. If you've got $100,000 in ordinary income, it doesn't matter if you have $100,000 in dividends or $1 million in dividends. That ordinary income is going to be taxed at the same rate (although it could be affected by some deduction phaseouts based on AGI.)

The second thing it means is that the opposite is not true. Increasing ordinary income can push your qualified dividends and capital gains into higher brackets. Let's say a single person has $30,000 of taxable ordinary income and $5,000 in qualified dividends. Those dividends are taxed at 0%. But if that person gets a better job and now has $60,000 of taxable ordinary income and $5,000 in qualified dividends, the dividends are taxed at 15%.

In an example more relevant to those on this website, if you're Married Filing Jointly and go from a taxable ordinary income of $400,000 to $600,000, your $100,000 in qualified dividends are now going to be taxed at 20% instead of 15%. If you had increased your dividends by $200,000 instead of your ordinary income by $200,000, only $200,000 of your now $300,000 of dividends would be taxed at 20%, because dividends stack on top.

The third thing it means is that your deductions are taken from your ordinary income, NOT your capital gains. This is not so intuitive, but it is indeed the way it works because of this worksheet. By the time you get to line 15 of the 1040 ( line 1 on the worksheet), you've already applied all of your above-the-line and below-the-line deductions to arrive at your taxable income. THEN, you subtract your entire sum of qualified dividends and LTCGs from that taxable income amount. Thus, the deductions apply to ordinary income, NOT qualified dividend/LTCG income.

Qualified dividends and long-term capital gains (as well as collectibles, capital gains, and depreciation recapture tax) always stack on top, and that is a good thing for you, the taxpayer.

If you need help with tax preparation or you’re looking for tips on the best tax strategies, hire a WCI-vetted professional to help you figure it out.

What do you think? Did you ever consider this before? Will it affect the way you arrange your financial life?