By Dr. Rikki Racela, WCI Columnist

By Dr. Rikki Racela, WCI ColumnistAs part of my obsession with becoming more financially literate, I came across the behavioral finance research of Hal Hershfield, a professor at UCLA. Being a neurologist and now a columnist for the finance-related website that you are reading right now, I was completely fascinated with Hal’s research on how we view our future selves. For most people, it's that of a complete stranger. This may explain why, at baseline, most people don’t care to save in their 401(k); you are saving money for what your mind sees as a stranger. Even more fascinating is his experiments where showing people aged pictures of themselves made them more inclined to save in that 401(k) or other retirement vehicle. Mind blown!

Armed with the knowledge of his research, I immediately used facial aging software on my iPhone and rendered aged pictures of my wife Meredith. I have written previously about how my better half has no propensity to save for retirement and doesn't have any interest in finance. I was also previously financially illiterate so it was truly the blind leading the blind when we bought whole life insurance and lost $50,000 and when we were $31,000 in credit card debt despite being two high-income docs. The pain of that loss and the resulting burnout fired me up to learn as much as possible about personal finance, but the same fire was not lit for Meredith. I thought Hal had given me a way forward.

I showed Mer her aged future picture, and her first words were, “Wow, I look terrible! I would never have my hair like that!”

Me: “Actually, you look great! . . . By the way, do you feel like we should save more for retirement, so that face you see in front of you will live an awesome retirement?”

Mer’s response (sort of disappointing): “No.”

What?! Was Hal’s psychobabble and research about getting more connected to our future selves justified only in a controlled laboratory setting without applicability in the real world? Or maybe I should have used better facial aging software rather than the free ad-filled iPhone app version? In the following paragraphs, I will outline a little more about Hal’s research into our future selves, how I believe it really does hold water and applicability in the real world to make us better investors, and discuss why my wife’s response shouldn’t be too surprising.

Normal Brain Processing of Our Sense of Self

We should briefly describe the neural basis and processing in the brain occurring when forming our sense of self. A paper written by Conway, et al entitled “The Construction of Autobiographical Memories in the Self-Memory System” for the Psychological Review describes what we know about which structures are involved in our sense of self. Don’t worry, you don’t have to read the paper. Here are the highlights. The hippocampus, thought to be involved in memory, will light up on fMRI along with the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), adjacent rostral anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), precuneus, and posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) when questions are asked regarding a subject’s sense of self. In essence, your sense of self relies on memories, presumably of previous actions or past decisions and perceptions, and your brain’s memory structures are in dynamic communication with brain areas that encode the sense of self.

Not only are past memories involved in building the sense of self, but current stimuli that your brain might be processing go into your self-perception. In a construct called “embodiment,” our brain uses current senses and processing of information ongoing right now in the development of our sense of self. A nice summary of this can be found in the paper by Arzy, et al, “Neural Basis of Embodiment: Distinct Contributions of Temporoparietal Junction and Extrastriate Body Area” in the Journal of Neuroscience. As the title of the paper suggests, the temporoparietal junction and the extrastriate area have heavy communication with brain structures involved in the sense of self. The temporoparietal junction processes current information from thalamic, limbic, auditory, and somatosensory systems while the extrastriate area processes the current visual information you are receiving.

Temporal Discounting and the Future Self

Based on the above discussion, you could see the dilemma of saving for your future self; the brain does not use the future to define your sense of self, but rather past memories and current sensory information. Does that mean we are doomed never to make a connection for our future selves and save for retirement? Luckily not.

Professor Hershfield is a prolific researcher who has discovered different brain activation patterns in the anterior cingulate cortex of our brain, a structure vital in recognition of our sense of self when considering questions regarding our current and future selves. In the paper “Saving for the Future Self: Neural Measures of Future Self-Continuity Predict Temporal Discounting,” where Hal was the lead author, the authors sought to localize in the brain differences in perception of the current and future self and its relationship to temporal discounting. It has been well known that money now is worth more than money in the future, known as temporal discounting. This prevents people from saving for retirement.

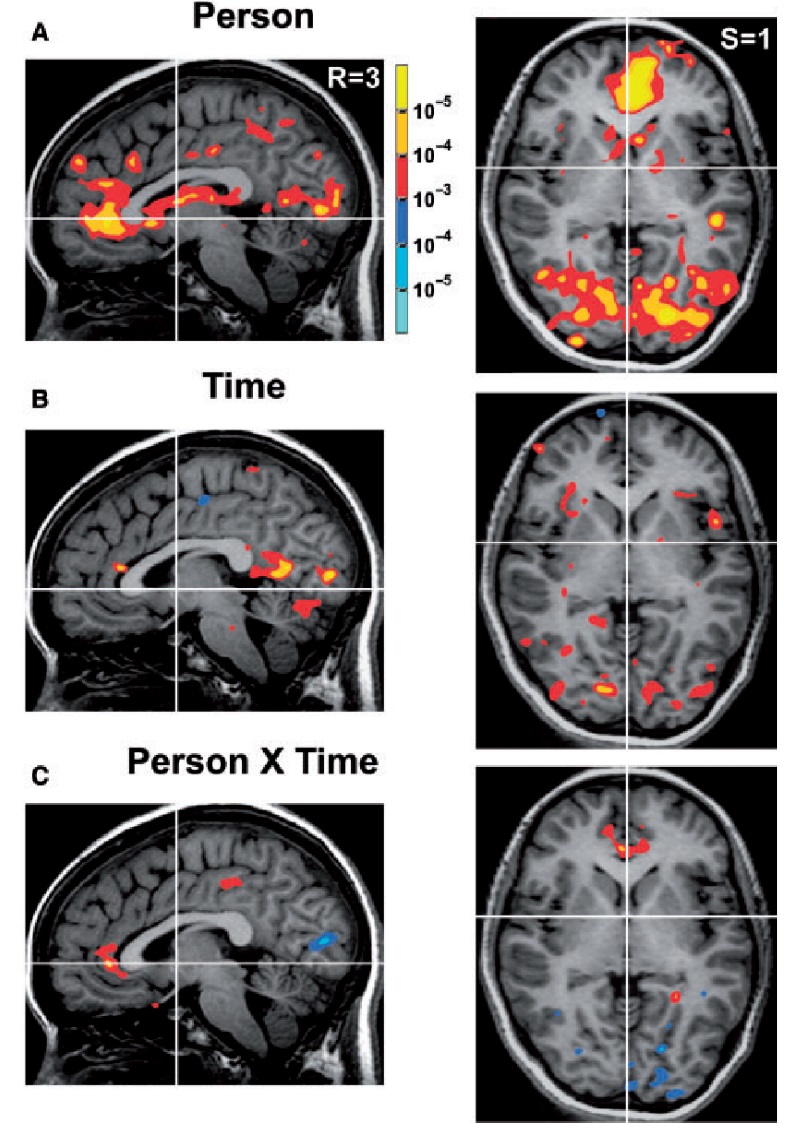

The authors took 18 Stanford students, placed them in an fMRI machine, and asked them to rate several descriptive words on how likely they describe their current self and then their future self. The brain areas that were activated were recorded. One week later, those same 18 subjects performed a temporal discounting task where several questions regarding taking money now vs. taking more money later were presented. What they found was astounding—the students who had more propensity to wait for more money in the future were the ones who had the rostral anterior cingulate cortex light up in the fMRI machine! The results are reproduced in the figure below.

Essentially, you can predict who will save more in their retirement accounts by seeing if the rostral anterior cingulate cortex is activated when thinking about your future self! As mentioned before, the anterior cingulate cortex is a brain structure heavily involved in recognizing your sense of self, implying that the reason you might save more in your retirement accounts is because you don’t see your future self as a stranger. Instead, you see yourself as you.

More information here:

Visualizing Your Way to Wealth

Saving More for the Future Self

Dr. Hershfield’s previous work begs another question: is it possible to get people to save more for retirement by getting “closer” to their future selves? In this vein, Hal and his study group performed experiments showing subjects either aged or non-aged computer renderings of themselves and then asked them various questions, including contributions for retirement. The methodology and results are published in “Increasing Saving Behavior Through Age-Progressed Renderings of the Future Self” by Hershfield, et al. In these sets of experiments, subjects shown the aged pictures of themselves consistently chose to save more for retirement than the control group shown pictures of their present selves. Eureka! Did Hal and his team solve America’s retirement savings dilemma? Should we all just see aged pics of ourselves, and we will automatically save more for retirement?

Not so fast. Hershfield, et al did mention significant limitations to their work. First, they were trying to use software, even virtual reality technology, to create as real a picture of the future self. But really, it is possible that just provoking the imagination of one’s future self could already encourage somebody to save for retirement without the aged picture renderings. Second, subjects were doing these tasks in the space of a couple of hours. Seeing aged pictures of yourself and then asking immediately if you want to save for retirement is one thing; seeing aged pictures of yourself and then maybe being distracted by screaming kids, a barking dog, dinner cooking in the background and your spouse playing on the computer so you can’t log in to increase retirement contributions is totally different. Third, the subjects in Hal’s experiments were college students. Do aged pictures affect older savers who might be temporally closer to their retired self? Finally, Hal and his team were using pretty sophisticated university-quality picture-aging virtual reality software. I'm not sure the free or $2 age-imaging iPhone app will compare in terms of quality when aging your selfie into a retired older you.

Dr. Hershfield and his team’s fMRI findings. (A) Brain regions correlated with Person (self > other), including the MPFC and rACC. (B) Regions correlated with Time (current > future), including the posterior cingulate. (C) Person x Time, selectively activating the rACC. rACC= rostral anterior cingulate cortex

More information here:

Yes, Risk Tolerance Can Be Modified: You Just Have to Rewire Your Brain

Should I Still Get Cozy with My Future Self?

I would say yes. Based on Hershfield’s work, you should at least try and activate your rostral anterior cingulate cortex by looking at aged photos of yourself, especially if you are having difficulty saving for retirement. His work provides key insights into using our own brain’s pathways regarding sense of self and trying to pull that sense of self through time to the present to get us to save more for retirement. And it’s just so easy to download a free picture aging app and see aged renderings of a future you. It took me no money and 10 minutes to do his exercise with my wife, so there's very little downside. Even if you know you are actively doing this exercise to make a connection to your future self, this exercise can still be very effective, because you are reinforcing the behavior of saving for the future.

But Rik, didn’t you say this aged picture mumbo jumbo didn’t really work on your wife?

Yes, this is true, but my wife and I have lived through a financial trauma. And in the depths of $31,000 of credit card debt on top of $315,000 in student loan debt and a $1.01 million mortgage, we couldn’t help but ask ourselves, “Is this what it’s going to be like for the rest of our lives???” Yes, Meredith and I had already made a connection to our future selves through the pain of being financial failures and paying the price of poor past decisions. As we were fighting over losing $50,000 in whole life and being in credit card debt because we ignored finances, our future selves became a painful present.

At first, it was difficult for us to connect to our future selves. Both of us are doctors, and society has told us that doctors are rich, meaning that we shouldn't worry about our future selves because doctors are rich now and even richer in the future. Then, this façade came crashing down. We didn’t need facial aging software to connect us to our future selves; pain caused by mistaking a salesman for an advisor did that for us. When you feel financially stuck, you really feel stuck—now and in the future. I bet that’s when both of our rostral anterior cingulates started lighting up when thinking about the future. We felt defeated, and we promised ourselves that we would never feel that financial pity ever again. We promised our future selves. So, we got on financial track, and now we have a written financial plan to enable us to live a future self of abundance and fun.

I didn’t mention what my wife said after her negative reply on saving more for retirement after seeing her cheap facial aged picture. Here's what she said:

“Are you trying some neuro/brain trick on me? I thought you said we’re saving enough for retirement so we’ll be happy. We don’t need to save more. And are you going to write about this or something?”

As I’m writing this now, I have to hand it to my wife. She knows her future self, and she definitely knows future me very well.

Have you tried increasing your savings rate by looking at aged pictures of yourself? Or do you think our brains are too complicated to train your rostral anterior cingulate cortex to fire in terms of retirement savings? What else can motivate us to save more for retirement?