[EDITOR'S NOTE: Please be advised, the SAVE repayment plan is currently held up in the courts. We will update you at a later date when we have answers.]

Student loans periodically become hot political issues or sources of controversy. At StudentLoanAdvice.com, we strive to remain neutral and offer the most objective perspective possible. However, it is impossible to entirely remove our opinions from what we write and say when consulting with borrowers about their student loans.

Our No. 1 priority is to help you navigate the mess of student loans and utilize all legal strategies available to you. Today, we’ll cover eight controversial areas of student loan management and talk about the legality, ethics, and policy implications of those various strategies.

#1 Income Driven Repayment Forgiveness (20 and 25 years)

It is well known in The White Coat Investor community that Dr. Jim Dahle despises income driven repayment (IDR) forgiveness, even if he grudgingly admits there are times (more and more as IDRs become more generous) when it is the best plan for someone. He hates the idea of doctors still being saddled with student loans in their 50s, well past the halfway mark on their career. I don’t love this as an option for borrowers either, but with recent changes to student loan programs, I want to give this another perspective.

Most borrowers should either pursue Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) or live like a resident and pay their loans off in 3-5 years out of training. Both of these approaches tend to be the most cost-effective, and they are completed relatively quickly after school or training. Compared to IDR forgiveness, they have a huge advantage of taking less than five years after a doctor finishes training.

But what if your student loans are 3-4x your income? What if your career plans don't include full-time work or a government or nonprofit employer? And what if there’s no way you can afford to make those huge mortgage-sized student loan payments?

This is where IDR forgiveness may be the best option for you.

IDR forgiveness is when a borrower enrolls in an IDR plan and makes payments for 20-25 years. When a borrower reaches their forgiveness term, they pay taxes on the outstanding student loan balance. Say you owe $400,000 in student loans and are in a 40% tax bracket. You could pay a $160,000 tax bill, commonly referred to as the “tax bomb,” in the year your loans are forgiven. Yes, it’s painful and not optimal after having paid on the loans for so long. But you do have two decades to save up money for the tax bomb. Incidentally, until 2026, IDR forgiveness is actually tax-free, and it's possible that this date could be extended by future legislation.

SAVE, ICR, and old IBR require 25 years of payments while PAYE and new IBR require 20 years of payments.

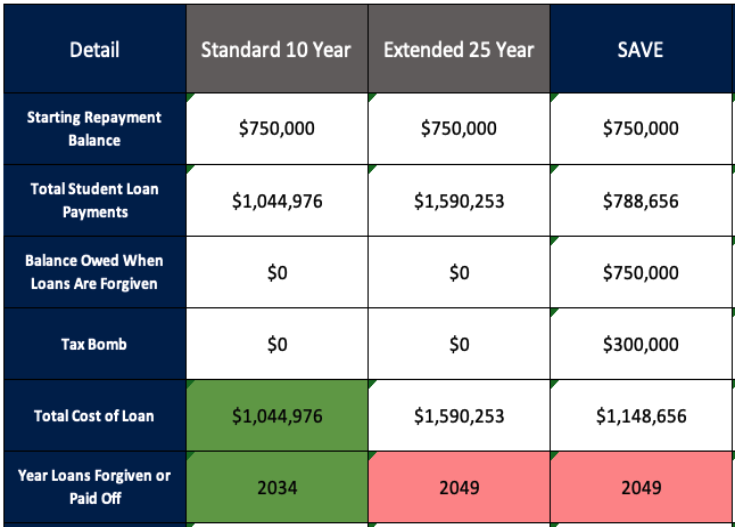

Here’s a scenario where a borrower may consider IDR forgiveness. You’re an orthodontist and you borrowed $750,000 at 7% for your undergrad, dental school, and residency, something that wouldn't be uncommon for a dental specialist. Suppose you're a divorced parent of two and an associate in a private practice, and you make $250,000 per year. We'll assume a 3% cost of living adjustment over time.

If you followed a standard 10-year repayment plan, you would pay around $8,700 per month, a total of $1.04 million. If you followed the extended 25-year repayment plan, you would pay about $5,300 per month, a total of $1.6 million.

In SAVE, your monthly payments are based on your income, and we’d expect an average monthly payment of about $2,629 for a total of $788,656 over 25 years. Your student loan balance at that time would still be $750,000. If that $750,000 were forgiven and you had a marginal tax rate of 40%, the tax bill would be $300,000. Thus,

Total cost of the loan = $300,000 + $788,656 = $1,148,656

In this scenario, SAVE is more than the standard repayment, but it's far less than the extended plan. Another factor is whether the borrower can afford a payment that is nearly $9,000 per month in standard repayment. It would obviously be much easier to make the $2,600 monthly payment and save for things like retirement, college savings, home, etc.

If a borrower plans to pay off their loans over a term longer than 10 years, they should strongly consider IDR forgiveness. In this scenario, IDR forgiveness could save them around $400,000. Moreover, this extra $400,000 could theoretically be invested and potentially more than double due to compound interest and appreciation over 25 years.

IDR forgiveness can be helpful to some. Give it strong consideration if you have a high debt-to-income ratio.

#2 Borrowing More Than You Should

Many of us are raised with the mentality to pay down our debts as soon as possible, believing that the quicker we can rid ourselves of debt, the better. Do you want to pay or receive interest? This common wisdom applies to many types of debt, including mortgages, car loans, consumer debt, and student loans. However, federal student loans are a bit unique in that you may never have to pay them back.

Imagine borrowing $300,000 and only paying back $100,000—just 30 cents on the dollar. For some, this might seem heretical, but it’s becoming more common with loan forgiveness programs like PSLF and even IDR forgiveness.

I frequently meet with graduate students planning to borrow large amounts to attend school. Some have no savings. Some can cover a year or so. Others have enough to pay it all as they go.

In the past, I advocated for cash-flowing tuition and borrowing as little as possible. However, given the current generosity of our federal student loan system and the programs available to doctors in and after training, such as SAVE and PSLF, I've reconsidered the dilemma of borrowing for education vs. paying as you go.

While I still see the value in paying down debt quickly, I now believe it is much better to borrow now and keep your options open. We don’t like the lesson this teaches—borrow more and rely on the government and loan forgiveness. However, it's tough to tell a heavily indebted doctor to turn down hundreds of thousands of dollars in benefits on principle. Hate the game, not the player. Call your congressperson, but be sure to fill out your PSLF paperwork.

When posed the question of paying down loans or borrowing, Jim has often said, “I hate myself for telling medical students to borrow when they don't have to, but I do think that's the correct answer now for someone with cash going into medical school and it is what I would do if I were in your shoes.” He even wrote a whole article about this very topic.

More information here:

The (Nearly) Perfect PSLF Situation for a Physician

#3 Favor Pre-Tax Accounts Over Roth While in Training

I am an advocate for starting your investing or retirement accounts as early as possible—even if it's $10 per month. Building this habit will literally pay you dividends in the long run. The rule of thumb has long been to use Roth accounts while in residency and the other low-earning years of your career. Remember “Roth is for residents?” Well, there are exceptions to this rule of thumb, too.

If you scour the blogosphere, the WCI Forum, and Bogleheads, you’ll find some heated debates on the difference between saving in a Roth vs. a traditional account.

We are told by the financial industry to favor after-tax accounts in our lowest-income years. Income is lower, so we are taxed less. Our progressive tax system is one that, as income increases, we will pay more to Uncle Sam (generally). Then, when we retire and start to take money out of retirement, perhaps we’re in a higher tax bracket and tax rates have increased, as well. Those Roth dollars have already been taxed, and the appreciation in those accounts is not taxed when we take it out. Pretty sweet deal, right?

When you are in residency, money is usually tighter, and your income is the lowest it will be for your career. Additionally, you may be in an IDR plan where payments are based on income. The lower your taxable income, the lower your payments.

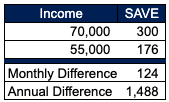

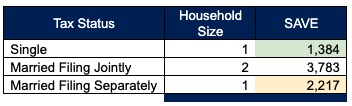

See below for a breakdown of monthly payments:

At an income of $70,000, your payment is $300. If you contribute $15,000 to your pre-tax retirement account—a 403(b) or 401(k)—it would lower your income to $55,000. That lowers your monthly payment by $124 per month and about $1,500 per year. Having lower monthly payments while in training can be helpful for budgeting, especially if you’re living in a high-cost-of-living area.

For docs in training, this strategy could save you between $4,500-$12,000 depending on the length of your training. If you end up doing PSLF, the reduced payments help to bring down the overall cost of your loan.

More information here:

Should You Make Roth or Traditional 401(k) Contributions?

Tax-Deferred vs. Roth Contributions: A Deep Dive

#4 Filing a Tax Return as an MS4 and Using That to Certify Income

As a new intern, you have two methods available to you to certify your income to the Department of Education. You can send them your paystub, or you can send them last year's tax return—which typically documents an income of $0. Obviously, your IDR payments will be much lower on an income of $0 than on an income of $60,000. That's why it is generally recommended that MS4s with federal student loans file a tax return for their MS3/MS4 tax year, even if they are not required to file. This is somewhat controversial, but the rules certainly allow one to use either method to document income. On the other hand, if an attending is going back into fellowship, it is to their advantage to use their first fellowship paystub to document their new lower income.

#5 Potentially Fraudulent Strategies

Most would agree that the above strategies are legal and ethical. However, there are plenty of other strategies being used that may be not. Let's talk about some situations where people probably take it too far.

Leaving Your Job and Recertifying Income to Lower Your Payment to $0

I see this happen when a doc leaves a job and calls their loan servicer to have them drop their payment to zero. This doc takes their next job a month later, and now they have $0 payments for an entire year. Once that leave ends (parental leave or a job gap), they could recertify using their most recent tax return to have payments pick up again.

Front-Loading Your Retirement Account on Your First Paystub

Submitting a pay stub for income documentation is generally a reasonable way to recertify income. However, it's possible to game the system with that pay stub, such as by making a huge retirement account contribution that month. While some “student loan advisors” out there recommend this, I'm not comfortable doing so. But here's how it works.

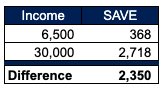

Let’s suppose you make $30,000 a month for an annual income of $360,000. If you front-load your retirement account in a traditional 401(k) and contribute $23,500 on your first paycheck, it would drop your take-home pay to $6,500 for that month. If you use that pay stub to document your income for IDR, your payments would be based on $6,500 per month instead of $30,000 per month.

As a result, this could lower your student loan payments by $2,350 per month and $28,200 for the year. To me, it seems too shady to take this approach, and I think you should submit income documentation that more accurately reflects your income. It seems different to me than using last year's tax return for a full year.

Documenting Income Using Only a Paystub When You Have Other Income Sources

Another strategy that I have seen recommended for business owners—generally dentists—is to pay oneself creatively. As an S Corp owner/employee, you can pay yourself whatever is categorized as reasonable income and take the rest of your income in distributions. Business owners will do this for a variety of reasons, including to save money on taxes.

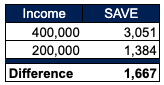

Some borrowers choose to submit only their W-2 or pay stub—which reflects their salary—for income certification purposes instead of using their tax return that reports both salary and distributions. This approach can result in a lower reported income, potentially leading to lower payments under IDR plans.

For example, a solo practice dental owner pays themself $200,000 in salary and $200,000 in distributions. If they submit a tax return to document their income, payments are based on $400,000 of income. If they certify income using a pay stub instead, payments are based on their salary of $200,000.

How the dentist documents their income has a huge impact on their student loan payments. In this scenario, it is more accurate to submit a tax return that captures their total income.

This can become complex as distributions can vary from year to year depending on your industry. If you’re in a situation where it is impossible to project what business income/distributions would be, you could submit an employer letter detailing your expected salary and distributions for the year. It's better to give an estimate rather than nothing at all.

Declaring That You Cannot Access Spousal Income

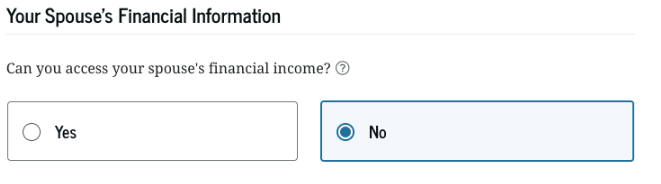

Another strategy I’ve seen employed by married borrowers is marking no on this question:

Married borrowers will say “no” so they don’t incorporate their spouse’s income for student loan payments. This would allow a married borrower who files jointly (MFJ) to base their student loan payments only on their income. Generally, you can only exclude spousal income through Married Filing Separately (MFS). Opting for MFJ is often more attractive from a tax standpoint due to the potential for lower overall tax liability.

However, you should only mark “no” if you are separated or if you have been abused or abandoned by your spouse. Instead of marking “no” on this question, just file your taxes MFS to keep your payment lower.

When considering any of these strategies, you, at a minimum, need to ask yourself what your integrity is worth and consider the possibility of actual criminal prosecution for fraudulent behavior.

#6 Delaying Legal Marriage to Reduce Repayment Complexity

I trained as an accountant, and I have worked in the financial world for over a decade. I help doctors tackle complex financial questions, and sometimes I feel like a marriage therapist, as well. Though I’m far from qualified in couples therapy, I receive this question at least once per month: “Should we get married”?

This is a very personal question for each individual, and as someone who is married, I am biased. However, marriage does impact your finances, particularly regarding student loan payments.

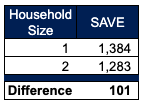

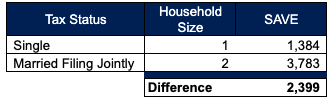

When you are single, your student loan payments are based solely on your income. When you legally marry, your spouse’s income can be incorporated into the payments. If you file jointly, their income will be used for the payment calculation. Moreover, having one income instead of two increases your household size and your poverty line deduction.

For a household size of one in SAVE, ~$34,000 is deducted before your payments are calculated. If you make $200,000, $34,000 is deducted to calculate your discretionary income = $166,000.

For a household size of two in SAVE, ~$46,000 is deducted before your payments are calculated. If you make $200,000, your discretionary income would be $154,000.

If your spouse does not have an income, it can help lower your student loan payments to get married.

Most of the time when a couple approaches me about marriage, they are both earners. What if spouse A makes $200,000 and spouse B makes $300,000? In this situation, although they receive a larger deduction for household size, this can more than double the payment.

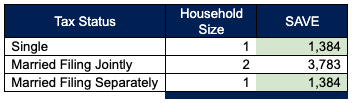

It can come as a rude awakening at the end of the “honeymoon stage/first year of marriage,” when your student loan payment is so much higher than it was previously. Filing separately can help solve this issue, right? If you file separately in SAVE, it allows you to exclude spousal income, but it also drops them from your household size when your student loan payments are calculated.

Bingo, problem solved. Payments are back to what they previously were before marriage.

But I as a CPA now enter the conversation . . . it’s usually more expensive to file separately, as you lose out on various deductions and credits.

How much more would you end up paying in taxes to file separately vs. jointly? In our experience, filing taxes separately as a married couple can sometimes result in little to no difference in taxes owed. However, there are instances where it can lead to an additional projected tax liability of $50,000 or more. You just have to run the numbers.

Understanding how this impacts your taxes is imperative when you’re running the numbers for student loan payments. If you’re having trouble understanding your taxes, take out the hassle and hire a vetted tax professional.

An example: this couple filing separately would increase their tax liability by $10,000 per year. This $10,000 is effectively an increase in student loan payments. If we calculate the monthly impact, $10,000/12 = $833. Here’s an update to our table.

MFS is still cheaper than MFJ. Yet, MFS is more expensive than filing as a single. This is why some couples will choose to put off legal marriage until their student loans are behind them.

Each situation is different, and you should consider the student loan and tax side when you make decisions. More often than not, couples will marry and file separately even though it may have saved them some money to wait until the student loans were paid off.

Some things in life matter more than money, though. Don't let the financial tail wag the life dog.

More information here:

How Does Married Filing Separately Affect Student Loans?

#7 Amending Tax Returns in Future Tax Years

The IRS allows you to amend your taxes for three years after filing. Because of this, some married borrowers file MFS to get lower student loan payments and then amend their taxes later to MFJ to collect a tax refund, essentially getting their cake and eating it, too.

Loophole or fraud? Certainly it does not appear that the Department of Education and the Department of the Treasury talk to each other about your filing status. It's a gray area, and neither Jim nor I are entirely comfortable with the strategy. But there are lots of people using it to reduce their overall loan cost.

If you’re planning to amend old tax returns, make sure you’ve filed the next return prior to amending an old tax return. Say your payments are based on income from 2023. You don’t want to amend the 2023 tax return before recertifying income using your 2024 taxes. What if the Department of Education does another review of your previous income recertification and sees that taxes have been amended? It may readjust your payment to a higher amount.

Before going down the rabbit hole of amending previous tax returns, it's a good idea to consult a tax professional.

Please note: If you are trying to amend a tax return from MFJ to MFS, you can only do this before the tax filing deadline. But you can go MFS to MFJ later.

#8 Filing an Extension on Your Taxes to Delay Higher Income

As a borrower in IDR programs, you are required each year to recertify your income to stay up to date on payments and in good standing with your loan servicer. During COVID, payments were suspended, and the annual income renewal was also delayed. Many people have been fortunate to have their next income certification delayed into 2025.

There’s a little-known hack where you can delay your tax filing to keep payments lower for longer. This is a strategy you should only employ if you are trying to keep your payments low for PSLF or IDR forgiveness.

If your income certification date falls between April 15 and October 15, you can likely file a tax extension for the current year, forcing the Department of Education to use a tax return showing your income from two years previous.

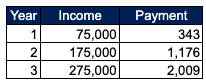

Suppose you make $75,000 in Year 1. In Year 2, you make $175,000, and in Year 3, you make $275,000. This is a common trajectory for those doctors who will finish training and have income increase exponentially from trainee to attending. Generally, when you recertify your income, the government will use taxes from the year prior. In this scenario, the borrower, now in Year 3, would use the $175,000 from Year 2 to calculate their payments. They certified their income on June 1 of that year.

Suppose this borrower extends their tax filing from April to October. Then, when they certify income in June, they use their most recently filed taxes. It would pull in information from Year 1 when they only made $75,000.

As a result, their monthly payment would be $343 instead of $1,176. Over a year, it saves this borrower $9,996. They could follow this up and do it the next year so their payment doesn’t jump right from $343 to $2,009 but $343 to $1,176.

Filing an extension on taxes can help keep your payments lower for longer when income is increasing. However, it still requires you to have paid all of your taxes come Tax Day in April.

Numerous strategies exist to help lower your payments and optimize your student loan management, ranging from controversial to straightforward. Regardless of your stance on these methods, you’re likely to find valuable tips that can save some of your hard-earned money.

What do you think? Are you using any of these strategies? Which methods do you think are ethical and which ones are not? Do you have questions about this?