By Dr. Jim Dahle, WCI Founder

By Dr. Jim Dahle, WCI FounderUnlike the Vietnam era, most Americans are now thankful for the service of their military members—including doctors, lawyers, pharmacists, and other “high-income” military professionals. This is a good thing; significant sacrifices are being made by these folks. However, the biggest sacrifices are usually not what a typical civilian might think. As we recognize Memorial Day today, here are 10 reasons you should thank military docs for their service.

#1 Getting Shot At

Most people think the reason you should be thanking military doctors is because they are putting their lives on the line every day for you. While technically correct, support personnel military docs are rarely shot at and even more rarely die as a result of an act of war. For the most part, they are far too valuable to hand a rifle to and send to the front line. Plus, they were never actually trained on how to use that rifle. As noncombatants, they're not even supposed to have the rifle in their hands.

Obviously, not all of our adversaries signed the Geneva Convention—much less abide by it—but the number of doctors who have died as a result of an act of war in the last 40 years can probably be counted on a hand or two. Choppers go down, mortars come over walls, and sometimes the rear areas become the front lines. But most military doctors are actually quite safe during their service. Nevertheless, being deployed to a war zone feels an awful lot like going to a hospital in March 2020. There is a palpable concern that something could happen to you, and all of a sudden, life and disability insurance policies seem a lot more important—and just like in March 2020, those insurances suddenly become a lot harder to get.

#2 Constant Threat of Deployment

A much more significant sacrifice made by military members is living for years with the constant threat of deployment hanging over their heads. They know that it's possible they'll have to leave their regular job and their family for months at a time with little notice. One of the greatest reliefs I experienced in life was separating from service knowing that I could not be deployed again. This was hardly a theoretical concern either. With just three months left in my service, I was deployed with less than 24 hours' notice on a deployment of an unknown length. We had plans to go on a trip to Puerto Rico two days later with my parents flying in from out of state to watch the kids. Katie went without me, and still to this day, we don't talk about Puerto Rico.

More information here:

How Much Do Military Physicians Make?

#3 Disrupted Career Path

The worst part of the Health Professions Scholarship Program (HPSP) or attending the Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences (USUHS, the military medical school) is that fourth-year medical students must go through the military match. This is a completely separate match from the civilian matches, and it does not work the same way. It does not favor the applicant and their career desires. The needs of the military are paramount. Instead of an anonymous computer program, the match is done by a handful of people sitting around a table horse-trading with your professional career. Now, these are generally good people who do care about you and do want to help you get what you want, but they are constrained by the needs of the military.

You can be matched into a program where you did not interview. Applicants are frequently informed that they will not be matching into their chosen specialty. However, even those who go unmatched are placed into some kind of training program, usually a rotating or surgical internship. Imagine you want to be a pathologist, cardiologist, or emergency doc. Well, now you're a surgery intern. You can apply again the next year, but there is a high likelihood you will spend 2-4 years as a “General Medical Officer,” with correspondingly lower pay and almost surely a branch of medicine you are not interested in practicing. There are fields of medicine that are very military-specific (aerospace medicine, dive medicine) that draw some people to the military, and there are lots of good things that can come out of a GMO tour. But it would be a lie to deny that pretty much everyone who ever matched into one was extremely disappointed about the disruption to their planned career path.

Specialty competitiveness is not the same in the military match as in the civilian match, and it varies from year to year. For example, emergency medicine in the civilian match has a match rate of over 90% for US medical school graduates. In the military, however, it's like matching into dermatology. The year I applied, the match rate in the Air Force was about 50%. The other 50% did an internship and a GMO tour. In fact, some people serve their entire obligation as GMOs and then go back to residency after they leave the service, essentially delaying the start of their chosen career by 4-8 years.

The rules of the match are also different. For example, points are given for prior service. This makes it much easier to do a second residency if you so desire, but it hurts a “regular” applicant that much more. When a recruiter says you're an officer first and a doctor second and that the needs of the military come first, they're not kidding. That's a big sacrifice, and military doctors should be thanked for it.

#4 Low Pay

Many military doctors come into service via the Health Professions SCHOLARSHIP Program. If ever there was a misnamed program, this is it. A scholarship implies that you are being given something. When we hear scholarship, we think “free money” right? HPSP should be named the Health Professions CONTRACT Program. Essentially, you are contracting with the military to pay for your tuition and expenses and pay you a stipend for four years in exchange for them later paying you less than you are worth for four years. How much less? That's highly specialty-specific. But let's do a quick comparison. Here is the most recent Medscape salary survey for various specialties:

Remember those figures are an average. Half of doctors make more. What do military doctors get paid? Let's take a look. They are paid in numerous different ways that make it confusing to calculate.

Base Pay

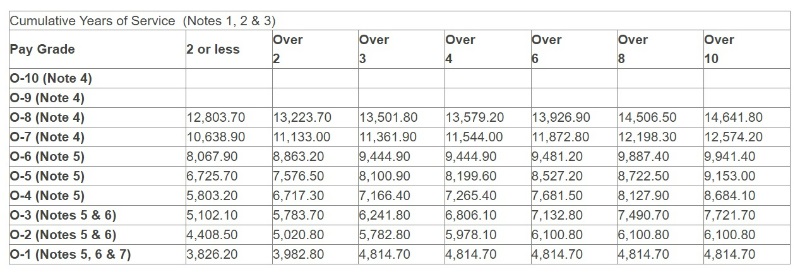

The first kind of pay everyone in the military gets is Base Pay. That is easily looked up in a table (this is the data as of January 1, 2024).

A typical doctor (at least one who matched) comes out of their military residency as an O-3 (Captain or Lieutenant) with three, four, or five years of service. Let's say three. They are paid $6,241 per month or $74,892 per year. Those with prior service can make a little bit more.

Basic Allowance for Housing

Every military member is either housed on base or paid a tax-free Basic Allowance for Housing (BAH). This varies by rank and location, but for an O-3 in Texas, that figure in 2024 is $2,730. Don't worry. If you are married or have kids, you get an extra $489 a month to pay for that extra space. But for a single person, that $2,730 adds up to $32,760 per year.

Basic Allowance for Subsistence

Every military member is eligible to be fed on base or to be paid a tax-free Basic Allowance for Subsistence (BAS). Interestingly, this figure is higher for enlisted folks than for officers. For 2023, officers are paid $316.98 a month or $3,804 per year.

Variable Special Pay

Every doctor, even those under obligation, is also eligible for a “special pay,” called Variable Special Pay (VSP). This can range from $1,200-$12,000 per year, but it's paid monthly. I couldn't figure out what the current number is (I bet it'll show up in the first few comments on this post), but it was $5,000 per year when I was on active duty, so I'll use that.

Additional Special Pay

Doctors are also eligible for another “special pay,” called Additional Special Pay (ASP). This is currently $15,000 per year.

Board-Certified Pay

Once you pass your boards, you get an additional payment of $2,50o-$6,000 per year. It was $2,500 when I was on active duty, so I'll use that.

Incentive Special Pay

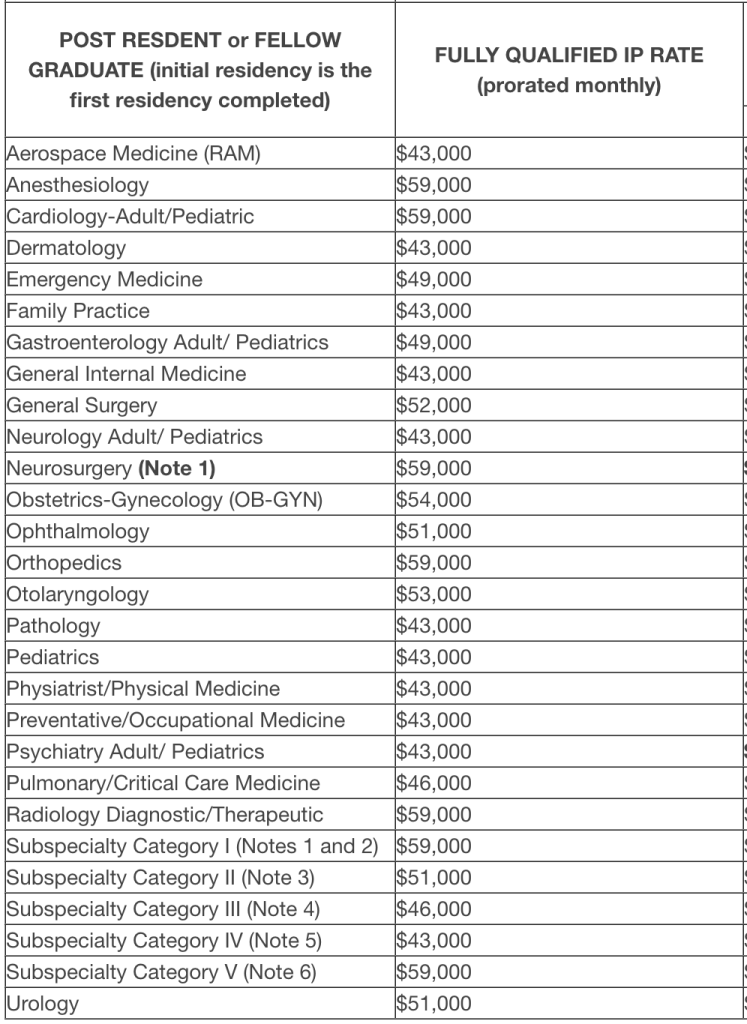

The final “special pay” that a doctor under obligation is eligible for is Incentive Special Pay (ISP). This annual payment varies by specialty. An intern gets $1,200, a resident gets $8,000, and a general medical officer gets $20,000.

These numbers rarely change. The EM number has only gone up $13,000 since 2006 when I came on active duty.

At any rate, a preventive medicine doctor or pediatrician gets $43,000 per year and an orthopedist, neurosurgeon, or cardiologist gets $59,000 per year. Notice that all of the other payments do not vary by specialty. The only variable one is the ISP. Thus, every military doctor under obligation is essentially making the same amount of money, at least within $16,000 per year. For those of you who have wished for more income leveling in the house of medicine, here is how it is done! Of course, you might not like the chosen level. Let's add it all up, shall we?

- Base Pay: $74,892

- BAH: $32,760

- BAS: $3,804

- VSP: $5,000

- ASP: $15,000

- BCP: $2,500

- ISP: $43,000

- TOTAL: $176,956 for a pediatrician fresh out of residency (less than $200,000 for 99% of residency grads)

Now, let's scroll back up to that Medscape survey. What do civilian pediatricians make again? Oh yes, $260,000 on average. And orthopedists make $558,000. The average physician in this Medscape survey made $363,000. The difference between $363,000 and $177,000 is $186,000. Per year.

What is the value of the HPSP scholarship? The current cost of tuition, books, and supplies at the University of Utah School of Medicine (where I attended and where tuition is now average to somewhat above average) is currently $45,864 for residents and $84,071 for non-residents. Add in the taxable stipend of $28,704 per year, and you get a total of $74,568-$112,775 per year. There is some time value of money there and a few minor tax advantages of military service (tax-free BAH and BAS, the potential to claim a tax-free state as your home, and some tax-free base pay while deployed). Due to inflation, however, civilian pay (and, to a lesser extent, military pay) is also likely to be higher upon finishing training than upon starting med school. Exact calculations are impossible, but the bottom line is that the average obligated military physician gets paid $177,000 plus perhaps $100,000 in educational benefits ($277,000). The average civilian physician gets paid $363,000. Some scholarship, huh? Obviously, due to the flattened pay system, the higher-paid specialties come out way, way behind, and the lowest-paid specialties can actually come out ahead. But there's no “free” money here. It's a contract, not a scholarship. This low pay is one of the reasons you should thank military doctors for their service.

Note that once your obligation is up, you are eligible for “Multi-Year Specialty Pay.” This varies from $12,000-$150,000 per year. It's specialty-specific and is in exchange for an additional commitment of 2-6 years. But a neurologist signing up for two more years is essentially trading that $100,000 per year educational benefit for just $13,000 per year. Even with a six-year commitment, an emergency physician is still working for 25% less than their average civilian counterpart.

#5 Unable to Live Where You Want

I didn't think this would bother me as much as it did. I also naively thought a brand new military doctor could be stationed somewhere cool like Germany, Japan, or Alaska. The best assignments are used to retain people who are eligible to get out. Those coming out of residency get the leftovers. While this is a personal thing and there are plenty of nice places to be stationed, there is a near 100% chance that you will not be living in your preferred location, especially during your first tour. Look at how much most doctors resist doing geographic arbitrage. It's not optional for military doctors.

More information here:

Life as a Military Physician – 10 Things I Loved About Being a Military Doctor

#6 Frequent Moves

While this doesn't usually apply to a military doctor doing one four-year tour to pay off an HPSP obligation, those who stay in the military must move frequently. I don't know about you, but I don't enjoy moving. Even though the military pays for it (and can even pay you to move your own stuff), it makes it much harder to build any sort of housing wealth. You can imagine what it does to your partner's career. Since you need to stay in a house for five years on average to make money owning it and since most military tours are only 3-4 years long, you, on average, lose money every time you buy. So, your options are to rent, to lose money, or to become a multiple out-of-state “accidental landlord.” Hard to get excited about any of those.

#7 Military Bureaucracy

You know how you hate the fact that your hospital is run by that MBA instead of a doctor? Imagine if it was run by a pilot, a tanker, or a submariner. The needs of the military come first, and that can affect your life in many unforeseen ways. Meanwhile, your patients can't get in to see you because you're off doing gas mask training all afternoon.

#8 Different Training

The quality of your residency training can be highly variable. It might not be all that different from the civilian world in pediatrics or OB/GYN. However, the more your specialty treats older, sicker patients, the more it is likely to be affected by doing it at a military medical center. I was faculty in an EM residency program in a big-name naval hospital for three years. Not a single one of my patients in those three years was intubated or got a chest tube. That has to affect training at a certain point. While residents rotate through civilian hospitals and their academics (and thus board scores) are often top-notch, you may not feel as prepared to see sick patients as you otherwise would be.

More information here:

How Physicians Are Affected When a Government Shutdown Is Looming

#9 Different Justice System

Military members are subject to the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ). It's a completely different legal system, and by joining the military, you are giving up a number of rights that most Americans enjoy. As a general rule, the system is much stricter. For example, adultery can be punished by forfeiture of pay, a dishonorable discharge, and a year of imprisonment. What's the penalty for that in the civilian world? Still, it's not as bad as lying to your boss. You get five years for that.

#10 Boring Medicine

You can't join the military if you aren't healthy. If you become unhealthy, you're kicked out. Your health is screened again when you are deployed so only the healthiest of the healthy are out there. Sure, there are still some sick dependents and retirees seen in military medical centers, but you can imagine how this affects your training and your practice.

Every Monday morning, for example, my ED was filled with airmen, soldiers, and sailors with minor illnesses whose employers required them to come to me to get the equivalent of a work note. Seriously, for the first five hours of my shift, I'd be seeing six patients an hour, few of which had anything that required prescription treatment. You're not saving lives and stamping out disease. Other specialties had their own complaints, like disability evaluations (seems like everyone could be at least 25% disabled by the time they separated). You are also highly likely to find yourself short-staffed—not just with support personnel, but with doctors. Difficulty recruiting and deployments can make it so that seven of you are covering a schedule that really needs 10 doctors. When not deployed, I generally worked the equivalent of 1.3 FTEs in my field.

And no, there's no overtime in the military. More work, less pay, what's not to like? Deployments can be feast or famine. Some people go to Fallujah and see a dozen trauma patients at a time. Others sit around in Qatar treating STDs and runner's knee for months. Hope you brought a book.

While there are many wonderful things about military service (great patients, camaraderie, early career leadership opportunities, interesting temporary duty assignments), there are real sacrifices involved even for doctors. The next time you meet one please thank them for their service. They really are making significant sacrifices to keep our troops in the field defending your freedoms.

What do you think? What other sacrifices do military doctors make?